Not long after watching Josephine Decker’s recent films Thou Wast Mild and Lovely and Butter on the Latch, I went to see Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. These decidedly different cinematic experiences got me thinking (yet again) about Manny Farber’s pivotal essay White Elephant and Termite Art, and how the distinctions posited in that essay might apply to these films.

It goes without saying that Nolan’s anti-environmentalist, objectivist space parable is White Elephant Art, a “masterpiece” smeared with great gobs of Kubrickian grandiosity (through a Spielberg filter, no less). The lumpen will likely be momentarily wowed by its hugeness and its pseudo-scientific/intellectual underpinnings, but (aside from a dangerous central message that the propagation of the human species trumps all other natural concerns) there is little to carry away from it. As a piece of film, it colors well within the lines, bringing nothing new (or even interesting) to the discourse.

Meanwhile, with her recent films, Decker (who is also an actress and frequent collaborator with fellow filmmaker Joe Swanberg, who himself plays a prominent role in Mild and Lovely) quietly moves about playing the termite, chewing away at the boundaries of genre, narrative form, aesthetic standards, and the divide between documentary and narrative. Her films have precedents and parallels, of course: chunks of Decker’s direction and general aesthetic (to say nothing of Ashley Connors’s herky-jerky cinematography) appear to owe a debt to David Gordon Green’s more “American gothic” forays, and her eye and ear for naturalistic conversation seems of a piece with Larry Clark, or perhaps the first third of this year’s A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness. Acknowledging these similarities is not a criticism, though: all it means is that Decker isn’t working alone, but instead gnawing as part of a team.

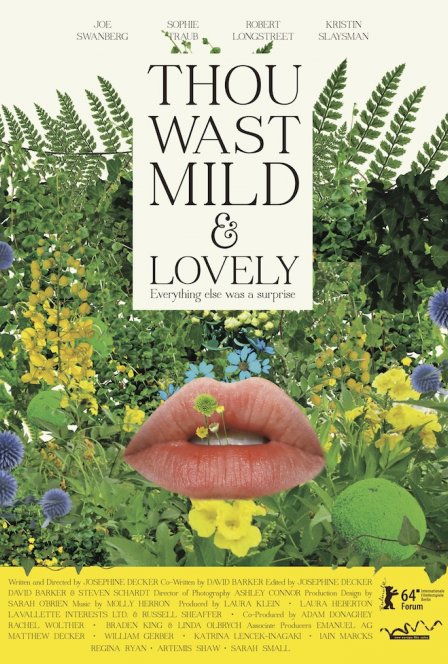

Thou Wast Mild and Lovely tells the tale of Akin (Swanberg), who arrives on a Kentucky farm at the beginning of the film to live and work with patriarch Jeremiah (Robert Longstreet) and his daughter Sarah (Sophie Traub). Akin is married, but initially endeavors to conceal it just in case any “opportunities” might arise. Arise they do, but the consequences aren’t quite the expected.

The film’s basic story echoes a wide variety of storytelling traditions, but is all shot through a distinctive lens that doesn’t obviously recall any of them. Decker has described the film as “an intimate magical realist erotic thriller: simultaneously a horror film, a farm drama, a comedy, a sexual romp, and a deep character study,” and she’s not wrong.

Butter on the Latch is not as fully realized as Mild and Lovely, but it stretches narrative conventions further. Isolde Chae-Lawrence and Sarah Small, essentially playing themselves, come together at a Balkan folk song and dance camp in the California woods. What starts as a quasi-documentary about these two friends and their complex relationship spirals into something else at an unusual pace, its trajectory more akin to that of a draining sink than to the straight lines of linear narrative. Conversations are improvised and intimate, funny and occasionally grating but always believable, making the film’s left turns all the more unsettling.

The skeletons of both Mild and Lovely and Butter are interesting, but not revolutionary. The devil, then, is in the details: the unembellished dialogue, the alternately frenetic and tensely static camera work, the pregnant silences, and the moments (in both films) where it’s nearly impossible to decipher what’s going on. It all adds up to a truly original, refreshing voice kicking in from the margins, small and human, but as real and revelatory and potentially disorienting as life itself. Decker’s art is nourishing and sustainable, honest and genuinely challenging. It is not the stuff of White Elephants or blockbusters, and for that I say thank fucking God.