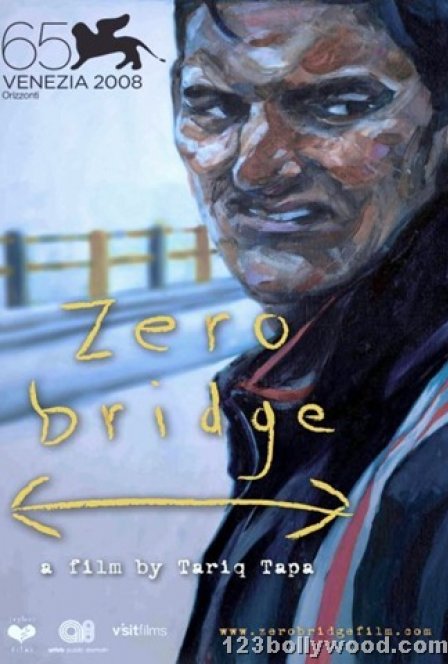

Set in the India-controlled region of Kashmir, Tariq Tapa’s Zero Bridge carves out a small, intimately detailed story of an intelligent teenage boy, Dilawar (Mohamad Imran Tapa), who lives with an abusive uncle while dabbling in pickpocketing and doing classmates’ homework for cash. Shot on a shoestring budget, the film employs a neorealist aesthetic, using rough, handheld digital footage and excessive close-ups to create a sense of immediacy and heighten its often tepid drama. It’s mildly successful in conveying the moral dilemmas of its protagonist with modesty, yet its clichéd central romance — between Dilarwar and Bani (Taniya Khan) — betrays its supposedly ultra-realist approach, bogging down the second half of a film purportedly interested in showing a culture rarely featured on screen with an arc that feels all too familiar.

The film begins by portraying Dilawar as something of an outcast — his adoptive mother gave him up after having children of her own, and his uncle (Ali Mohammad Dar) took him in against the advice of others — who is taken advantage of by most of his family and acquaintances. His status in fact mirrors that of Kashmir, a region that itself has been shuffled around and taken advantage of by other countries for centuries, yet the metaphor is never probed as Tapa takes a more direct, observatory approach throughout. While there is a certain authenticity to the local details on display, especially the often oppressive closeness of the family and the pervasiveness of police and military figures, Zero Bridge is never quite fully immersive due to its conflicting representations of its protagonist simply “being” and its increasingly apparent tactics to elicit unearned sympathy through convention.

It’s hard to fault a small film like this, one whose intentions are surely admirable, for succumbing to the “troubled boy in love” trope. And indeed, Tapa does a fine job of setting up the initial meeting between Dilawar and Bani at a shipping office, where Dilawar quickly recognizes Bani as one of his recent pickpocket victims. But while the coincidental meeting retains a certain degree of believability, we are then almost immediately asked to accept that this beautiful girl would willfully help Dilawar, who is already established as an intelligent boy, with his homework (or rather, homework that she assumes is his) for hours without pay. On the one hand, this enhances Dilawar’s moral struggle in an interesting way — his exploitation of Bani brings him closer to her, yet it also further betrays her trust — but it so glaringly conflicts with the film’s attempts at realism that it renders the whole thing relatively trite and emotionally dishonest. And while the film’s minimalist nature is its greatest asset in the first act, it ultimately makes its flaws and screenwriterly touches all the more apparent, resulting in some great individual slice-of-life sequences and some truly hackneyed ones.