Listening to renditions of Pachelbel’s Canon side-by-side in meantone temperament (a tuning system popular between the 16th and the 18th centuries) and equal temperament (the contemporary equivalent) is a decidedly physical experience. At the most fundamental level, the two frequency-arrangement systems reflect divergent approaches to epistemologically apprehending the world. The subtle shift in sonic register is really a shift in modality of apprehension, carrying with it contrasting ideas of harmony and dissonance, which are concepts that can only truly be felt. They vibrate flesh, move air, and produce assemblages of neurons and ear canals through structures of sensory legibility distinguished by three centuries of difference. Temperaments are discrete systems of sonic knowledge with their own internal limits, sensibilities, and contours, and as such, they are generative worlding practices.

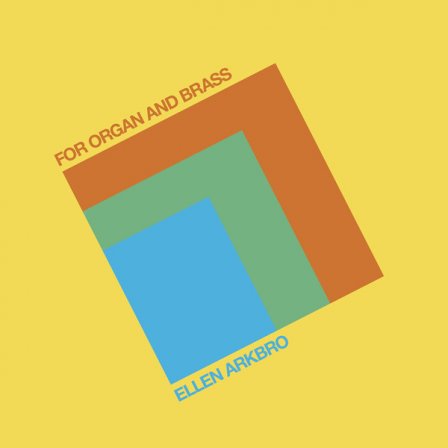

Stockholm-based composer Ellen Arkbro is known for her work as a guitarist, but she switched up instrumentation for her debut solo album, For Organ and Brass, performing it on an eponymous 393-year-old church organ in Tangermünd, Germany alongside accompanying horn, trombone, and tuba. The organ was built by the Hamburg-based Sherer-Orgel manufacturers, and it is tuned to meantone temperament; Akrbro chose it after trying numerous organs around the country and in this work transforms it into a conduit for locating potential between discrete temperamental ontologies of sound. As if to emphasize the difference between her work in meantone and the surrounding contemporary norm of music in equal, she drills the album’s sound-forms into the listening body through minimalist, repetitive patterns. The performers, meanwhile, play with minimum expressivity and tonal dynamics, laying out their tones as plainly as possible, like 2D plateaus jutting into space; there is absolutely no vibrato, and the only light shifts in loudness occur subtly on the second track. Describing her decision to go with the Sherer-Orgel in an interview with The Wire, Akrbro said it had “such a warm and organic sound, slowly pulsating, in perfect stability.”

Where you have to listen attentively to note the temperamental differences between performances of Pachelbel’s Canon, the listener is made to feel viscerally uneasy from the opening moment of For Organ and Brass’s lead title track. The two-tone harmony immediately sounds starkly out of tune, signaling clearly and concisely that the composition is engineered for an unconventional harmonic register. The following chords dispassionately ring out for nearly-identical successive durations of 10 seconds at a time for the remainder of the 20-minute piece. While “lyricism” might not be the first word to come to mind here, it’s in fact present in Arkbro’s chord voicings. Arranged just so, they demarcate sound-fields for the play between sustained frequencies, left to hang and cross-contaminate in the air like a dissociating plague of locusts.

The second track, “Mountain of Air,” is luminously pretty while still maintaining an air of strangeness. At times evoking the progression of an improvising jazz ensemble, the work alights like a loose handful of gossamer threads rubbed into soft heat. The frequencies arrive in close-knit packs and contrail like misty vapor; they’re stacked in close proximity to one another to contrast, and ultimately bolster, serenity with dissonance. “Three,” meanwhile, returns to the more disaffected compositional style of the lead track, taking, again, nearly identically-sustained steps through a seven-chord cycle on three horns for the entirety of its 12-minute duration. They move like dust-specked, unadorned cement walls or glassy sheets slightly bent out of shape by the wear of musical enactment.

Because the listening body is so unused to the record’s tonal register, there’s a pervasive sense of trudge to the proceedings; it isn’t used to contorting like this, and soon it’s weak from straining previously unused muscles found somewhere within knotted caverns of flesh. While the listener is vibrated by For Organ and Brass, the embodied strain of listening to these unfamiliar combinations of frequencies mostly fades into the background. They’re induced into a state vulnerable to the submerging of sound below the threshold of normative listening, where it can entertain affective configurations of another epoch in novel ways. Once the album’s done and the headphones are off, though, listening physiology is irrupted into a temporary liminal state as it adjusts back to the world. The entirety of sonic perception is submerged in a filter, lightly crackling like shimmering foil or an earthquake seismograph; the edges of individual frequencies seem to shiver or auto-refract from the top to the bottom of the sonic spectrum. The experience has an unsettling effect that disorients proprioception and, in turn, sense of self and of the world.

Interestingly enough, I have experienced this foil-filter-phenomenon before, but only after listening to technically advanced computer music by contemporary composers such as Gabor Lazar and EVOL. Their work and Arkbro’s presumably couldn’t be less similar — hers enacts an older musical template, while theirs resoundingly invokes the present — yet they occasion nearly identical processes of physiological disorientation. The comparison slightly bends a normatively linear conception of historical time, showing that two ends of a spectrum — “then” and “now” — might meet in the middle and become hopelessly entangled. Because of that, For Organ and Brass could have some value as a frame of reference for anyone struggling to retain a sense of the longue durée’s texture in these endlessly chaotic times. Either way, by tinkering with the archive and repurposing its artifacts for originally unintended purposes, Arkbro succeeds in creating magnetizing, thought-provoking work by turning the Western history of sound into a kind of raw material.

More about: Ellen Arkbro