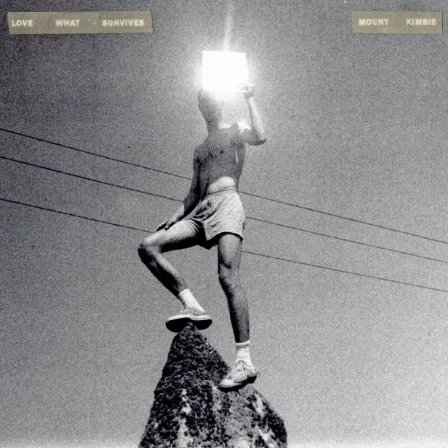

I can’t believe that this record didn’t already exist. Doubly so that the elevator-length description — “post-punk with electronics” — left any room for novelty whatsoever. Of course, it’s hard to communicate over the duration of an elevator ride that you intend to alter the very precepts of a genre. Sonically, Love What Survives is a sort of light-side answer to the churning industry of the never-quite-dead post-punk revival, akin in its position to the place of Mr. Mitch’s “peace dubs” among the broader, crueler landscape of UK grime. It’s too driving for dream pop, but too yielding for coldwave’s gloom. The drums, quite possibly programmed, remain a step less motorik than what the album art might suggest. Rather than incrementalism, this is the sound of musical progression by way of a headlong dive into something altogether new.

It took some time to hear what Mount Kimbie were doing. Crooks & Lovers, a wonderful document of its time, received wide acclaim and played a major part in ushering in what we faithful fondly recall as the “Majestic Casual” era. Despite a full three years passing in between, follow-up Cold Spring Fault Less Youth was a lot of the same. By then, that wasn’t nearly enough. While a new Mount Kimbie album doesn’t require a total vacuum of context, it seems to help if you can only vaguely recall what came before. Pressing play on Love What Survives, I remembered half of a track from Crooks & Lovers with the fondness given to everything new heard at 17; Cold Spring Fault Less Youth was a shadow of that, plus an inkling that there had been some ill-advised guitar incursions. With that in (or out of) mind, Love What Survives is a revelation — a summation of their work to-date without specific precedent for any individual track.

Although he only appears once, it would be irresponsible to discuss the album without mention of King Krule. Together with James Blake, he and Mount Kimbie form a sort of oligarchy over the domain of British melancholy. It’s that very note, struck with reckless sincerity by Krule and sublime clarity by Blake, that defines the record, allowing Mount Kimbie to explore whatever textural territory they desire safe in the knowledge that the town criers have shouldered the burden of narration. Their appearances are the only tracks for which vocal performances go beyond atmosphere or mantra, and for good reason: much beyond “Think about me everyday/ Forever” from “T.A.M.E.D.” or how the titular “You look certain (I’m not so sure)” would serve only to override, rather than augment, the lingering aftereffects of “I wanna fall forever if you ain’t by my side/ I wanna fall forever if you ain’t in my life” from “Blue Train Lines.”

This particular brand of middle-class British malaise is the result of absolute self-certainty confronted with a reality that undermines it. The feeling has a long history. Its scripture, Martin Amis’s The Rachel Papers, begins thus:

My name is Charles Highway, though you wouldn’t think it to look at me. It’s such a rangy, well-travelled, big-cocked name and, to look at, I am none of these. I wear glasses for a start, have done since I was nine. And my medium-length, arseless waistless figure, corrugated ribcage and bandy legs gang up to dispel any hint of aplomb… But I have got one of those fashionable reedy voices, the ones with the habitual ironic twang, excellent for the promotion of oldster unease. And I imagine there’s something oddly daunting about my face, too. It’s angular, yet delicate; thin long nose, wide thin mouth - and the eyes: richly lashed, dark ochre with a twinkle of singed auburn… ah, how inadequate these words seem.

Love What Survives is a blank canvas for the Charles Highways of the world, a palette for expression and interpretation that offers just enough direction to welcome even those for whom words fail. It is, in the parlance of the times, a “mood.” To that end, it’s without flaw, impressing a specific and inescapable impression for its full runtime despite minimal explicit instruction. Define artistic success as you will, but it’s beyond question that Mount Kimbie have here translated, and therefore transmitted, an entire state of being.

More about: Mount Kimbie