We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

10. Bestiaire

Dir. Denis Côté

[Metafilms]

The popular bestiary, or compendium of beasts, of the Middle Ages depicted, aside from the known science of the animals contained therein, moral lessons that reflected the belief that our world was actually the word of God made tangible. It’s a fitting title for Bestiaire, the Québécois documentary that gave us an unnervingly dispassionate view of, primarily, dead animals and animals behind bars. Unlike its medieval forebear, the film made no explicit commentary about the morality or immorality of the wild animal park or the taxidermy workshop on view, but the conclusions we were given agency to draw for ourselves were likely about our relationship to the natural world and any higher meaning that relationship might reveal. Zebras frantically tearing around their after-hours enclosure in a flurry of furiously dancing hooves (one of the most deeply terrifying moments on screen this year); a monkey with the sorrow of the ages in its eyes devotedly dragging an oversized teddy bear around its enclosure; an enormous exotic bird stretching its one remaining wing to a staggering width in a dark, narrow room: these images by themselves spoke volumes about the darkness of our place among God’s creatures, in relation to history and as they stand alone in the modern age, if you were willing to read them.

09. Let The Fire Burn

Dir. Jason Osder

[Zeitgeist Films]

If you cornered me at a holiday party and asked about my “favorite” movies of the year, I probably led with this one in the hopes that it will get the audience it deserves. Jason Osder’s all-archival documentary is a tough sell, and sounds medicinal when you try to describe it. The film details a racially-charged event from 1985, when a Philadelphia police raid on the compound of a black separatist group spiraled out of control. The botched raid ended in a city-sanctioned firebombing that killed 11 of the group’s members and burned dozens of houses to the ground. There’s power in the story itself, and in the themes of racism, civil disobedience, and violence it evokes, but the experience of reliving the story worked on me in unexpected and deeply moving ways. On a formal level Let The Fire Burn is an accomplishment of precise, clinical editing, but under the icy precision of the storytelling there’s a raw core of emotion. It’s a layered visual feedback loop, a warning that quotes Faulkner in newsreel footage and video depositions: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

08. Drug War

Dir. Johnnie To

[Variance]

Although it’s hard to pin down a director who has made over 50 films ranging from hyper-violent Hong Kong action flicks to bubbly romantic comedies, 2013 saw Johnnie To return to the form of his superb Election series with the release of Drug War. Set in mainland China, To’s film examined the parallel bureaucracies of the criminal underworld and state police force, and, in so doing, offered up a unique take on how crime operates in contemporary Chinese society. On the surface, Drug War appeared to adopt the black-and-white morality of classic gangster cinema: the dogged, stoic g-man embodied by Captain Zhang Lei (Honglei Sun) purposefully contrasted with bombastic characters like the laughing sociopath Bro Haha (Hao Ping) and the Machiavellian Tian Ming (Louis Koo). This dichotomy worked its way into the style of the film itself, transforming procedural realism into tragic opera. Contrary to many observations, the violence of To’s action films wasn’t so much toned down for this effort as it was bottled up until the climax. While To’s film maintained its outward binary morality, the finale’s brutally literal destruction of both the criminal and police apparatus hinted that the two sides of the titular “war” exist in dark symbiosis.

07. Before Midnight

Dir. Richard Linklater

[Sony Pictures Classics]

Most movie romances end with “happily ever after” or something similar. Before Midnight was the most romantic film of the year because it abandoned easy endings: sure, Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) were beloved characters after the other two Before films, but director Richard Linklater actually dared to consider how romance can exist after years of marriage, with a couple of kids along the way. His strategy was the same as before. The literate script was co-written by Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke, and it gave Jesse and Celine ample time to converse and argue. There was a constant push/pull of power in their relationship, now deepened since there was genuine emotional baggage instead of romantic folly. We followed them on holiday in Greece, culminating with a night in a posh hotel, and the movie was brave enough to consider how a couple still manages to preserve their sexual chemistry. The final argument between Jesse and Celine was as seething as anything from the previous two films, and because it ended with a quiet moment of empathy and grace, there was little doubt they were soul mates. The love in Before Midnight wasn’t happily ever after; day after day, it’s doggedly until tomorrow.

06. Upstream Color

Dir. Shane Carruth

[ERBP Film]

We waited nearly a decade for Upstream Color, Shane Carruth’s follow up to the metaphysical mind-bender Primer. Undeniably unique and utterly transfixing, his second effort was a hallucinogenic trip that connected the dots between parasites and psychosis, all while deftly expressing the dysfunction and symbiosis of codependent love. As challenging and demanding as its narrative was, it had a surprisingly simple logic: the worm-pig-orchid cycle. Alien and strange, certainly, but it cohered. It made us want to follow its disorienting path and try to keep up. We were drawn to its prismatic majesty as it overwhelmed our senses. Even when we didn’t know what it all meant, there was an understanding of two devastated people, a kinship with them. They were damaged, beautiful and so confused. Oh yes, the film was spectacular to look at, but the real pleasure was searching for what was hidden. Questions begat questions and our readings were our own. Carruth was kind enough to give us some closure as an antidote to the Lynchian aftertaste: as dialogue disappeared near the end, we were left with the language of nature and the thrill of vengeance. When it was over, many of us were ready to dive in again, and so we did.

05. Frances Ha

Dir. Noah Baumbach

[IFC FIlms]

Frances Ha felt like a big step forward — or at least a fresh start — for writer-director Noah Baumbach. Fortunately, this was all the while still retaining the restless intelligence, hyperarticulate characters, and barbed wit we’ve come to know and love from him for nearly two decades. Perhaps it was the film’s miraculously unaffected homage to the French New Wave, with its crisp black-and-white cinematography and charming Georges Delerue-scored montages, that helped balance Baumbach’s typically-caustic sensibility. More likely, however, was the distinctive influence of co-writer and lead actress Greta Gerwig, whose blitheful disposition and whimsical nature masked an undercurrent of unease and sorrow. Her lived-in performance as Frances, someone whose poor judgment and bitter luck keeps her perpetually out of step with the world around her, was simultaneously knowing and soulful. Although “heart” isn’t a term I’d normally apply to Baumbach’s work (and nor would I want to), Frances’s speech about “having your person” was one of the most unexpectedly moving scenes of the year. Some people said that the world didn’t need another chronicle of a struggling urban twentysomething artistic-type. While that may be true, Frances Ha was so funny and perceptive that it felt fresh and alive all the same.

04. Leviathan

Dir. Lucien Castaing-Taylor & Verena Paravel

[Cinema Guild]

Something akin to an episode of The Deadliest Catch as directed by Stan Brakhage, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Verena Paravel’s mesmerizing and intensely visceral Leviathan captured the brutal realities of life at sea in a dizzying, kaleidoscopic montage of perspectives. Shot with an array of tiny cameras attached to wires, chains, nets, and the fishermen themselves on a commercial fishing boat off the New Bedford coast, Leviathan was as close to a purely sensorial experience as cinema achieved in 2013, plunging the viewer into the ocean before thrusting them upwards into the sky to soar amidst the seagulls and cutting to every imaginable position on and inside the ship until the film became a beautiful yet terrifying abstract ballet of motion and stasis, blending the mundanity of the shipworkers’ routines with the implacable fury and violence of nature that surrounds them. Leviathan is not so much a traditional documentary as a synthesis of imagistic and sonic fragments that together form a complex system representative of the holistic relationship between man and nature; not one of symbiosis, but rather dominance and force in the face of a deep-seeded fear of the unknown and unknowable. As the ever-quotable Werner Herzog has said, “the common character of the universe is not harmony, but hostility, chaos, and murder.” Leviathan most assuredly agreed as the sheer savagery on-screen, as normalized and mundane as it has become to the fishermen, was a powerful reminder of what mankind has done and continues to do to survive, or at least to eat fish.

03. The Act of Killing

Dir. Joshua Oppenheimer

[Drafthouse Films]

Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing was the kind of film that made you wish you didn’t have eyeballs. Impossible to unsee and yet completely necessary to watch, it was an unfailingly outrageous reconfiguration of performative truth. The film dissected itself, weaving segmented blocks of narrative into a thread beyond categorization, beyond living and rationality, leading us into the blank space of what comes after murder, after the witnessing of death. Oppenheimer turned his camera over to the death squad (“gangsters”) responsible for killing and raping countless alleged Communists during the overthrow of the Indonesian government in 1965 and asked them to recreate the killings. It wasn’t even so much the matters of brutality as it was the flickers of instants wedged in between — “‘I look like I’m dressed for a picnic,” Anwar Congo said as he watched a playback of himself demonstrating how to strangle someone with wire, “I never would have worn white.” There was no moment not pinned with dread, the relentless sense of something seething in the undercurrent of what makes us human. It was a bigger anger than anything I’ve ever seen and the kind of film you’ll take with you to the grave.

02. Computer Chess

Dir. Andrew Bujalski

[Kino Lorber]

With Computer Chess, Andrew Bujalski applied the lo-fi, semi-improvisatory methods of his earlier films to his most ambitious project to date: a serious comedy depicting a convention of computer chess programmers in the early 1980s. The film found teams from universities and private ventures descending upon a nondescript hotel to test their programs against each other in rounds of tense one-on-one competition. The characters revealed just as much about themselves and their work during the off-hours — in all-night bull sessions, misadventures with stray cats and lost room reservations, and run-ins with a new-age encounter group sharing hotel space. With his mostly unknown cast fully inhabiting their roles, Bujalski layered each scene with off-kilter humor, psychological depth, and resonant observations about the implications of technology in American society. His much-heralded use of analog video equipment served as a means to an end, like the film’s meticulous period details — haircuts, clothes, cars, and especially computer equipment — which were never used as a punchline or for diorama-like preciousness. Bujalski situated artificial intelligence within its historical context, foreshadowing its future while examining how, as the last vestiges of the counterculture gave way to the Reagan Era, technophilia surpassed spirituality as a reigning American obsession.

01. Spring Breakers

Dir. Harmony Korine

[A24]

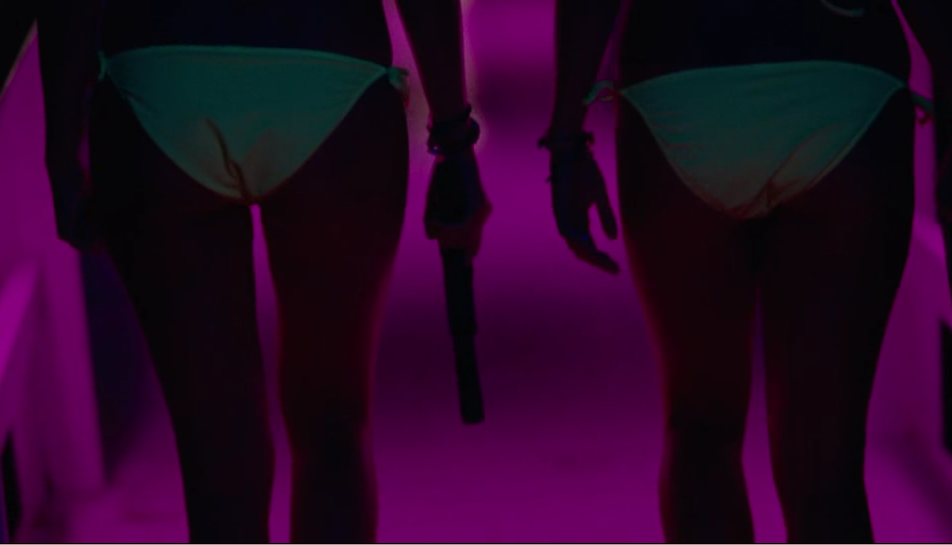

I don’t think any of us were really expecting to be as blown away by Harmony Korine’s latest film as we were when it opened. The press for Spring Breakers suggested pretty bluntly that it was definitely going to be bonkers enough to merit a viewing or two. But the concept felt a bit too obvious, even for Korine, who’s long since eschewed anything remotely approaching guile in his filmmaking. The early trailers were a kaleidoscope of James Franco all coked up and ridiculous trying to pull off a convincing Riff Raff impersonation, a whole bunch of raunchy hand-held footage of debauched teens on the beach, and some Disney/ABC Family starlets going buckwild with guns in bikinis and pants with lettering on their butts. It just seemed like such a bald-faced cash-grab. I mean, don’t get us wrong, we were sure we’d enjoy every minute of it. We just didn’t think it was going to be so damn great.

Korine wrought some of the most chilling and daring performances from a cast that — let’s face it — hasn’t really been doing their utmost to earn either of those adjectives in recent years. We were delighted when it became so obvious that Alien was the role James Franco was born to play, and no amount of Faulkner butchery is ever going to take that away from him/us. Ashley Benson, Vanessa Hudgens, Selena Gomez, and Korine’s own wife, Rachel, knocked it out of the park in ways we never thought possible, playing such ostensibly empty characters with a devastating gravity. The legwork required on Korine’s part to get those party shots which seesawed so jarringly between hypnotically beautiful and raw as hell was impressive enough in its own right, even before we stopped to admire just what it was he was accomplishing with all this exquisite trash.

If there’s one unifying thread that runs through the remarkably disparate gross of films that made our list this year, its a willingness to boldly experiment with staid forms of storytelling, and we could think of no better work that encapsulates this tinkering than this one, with its virtually straight noir storyline, that still manages to unsettle as much as any of the zanier work of his young days.

Spring Breakers was exactly the kind of eerily meditative, high NRG freskshit scattergash the world needed when it arrived this spring. If 2013 has branded itself the Year of Offensive Content™, then Korine’s latest was the harbinger of that label, touching on all the themes that would later consume so much of our time arguing about on the internet. Korine has spent the better part of his career trying to convince us that his movies are more concerned with the beauty (and, yeah, it’s often grotesque beauty) of what he’s throwing up on the screen than on the perceived or actual meaning of what’s underpinning them. If this hasn’t closed the door on that particular debate for you then nothing will.

We loved this movie unironically. We loved it because it was a cash-grab and it didn’t give a rip about being a cash-grab. We loved it because it shared a speed-freak continuity with the greatest of Terence Mallick’s visual work. We loved it — and we still do — because it was the best thing that happened in film this year, and there’s no one else in the world who could’ve pulled it off. In the end, this film was a great equalizer, a singular creation that bridged the insurmountable gap between auteurist vision and candy-colored materialist excess. Spring Break forever, bitches.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series