We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series

Introduction: The F Word, Dickparty and the Girls of Noise

Women have been working within experimental music for just as long as men, and yet sexism remains a prominent issue. The proliferation of sexist banter in both written criticism and in passing commentary strengthens the perception that male dominance remains unchallenged. Such instances are sporadically recorded on independent blog dickparty, which has seen a mild resurgence this year on the back of a number of interesting articles on the subject. Feminist webzine The F Word pointed me in the direction of the aforementioned Tumblr, while PR agency/webzine Meoko highlighted a study by Female:Pressure — an international network of female artists — who “gathered data that would allow them to evaluate the representation of women in electronic music through looking at the percentage of females on label releases, festival line ups and in Top 100 lists.” The result? “’[a] 10% proportion of female artists can be considered above average.’” It’ll be interesting to see how that will play out as the year-end countdowns mount up. But then again, saying that this has been a good or bad year for female musicians is ropey — female artists make exceptional music every year, as Meoko attests; it’s our awareness of it that is the problem.

In the 2008 documentary GUTTER: Girls of Noise, filmmaker Lauren Boyle takes her audience on a journey across the US to better understand the lives of female artists working on the fringes of experimental music. The film portrays a network of people practicing outsider art — from costume designers to transgender performers — artist who do not appear driven by money or profit. They discuss their reasons for wanting to partake in a supposed scene, which, like so many others, is perceived as male-dominated.

The documentary offers insight into alternative means of performance while outlining a number of interesting points: (1) that there isn’t necessarily a “scene” — which is itself a construct — for males to lord it over, as these musicians are simply operating within communities and small collectives made up of friends as opposed to a singular expansive group; and (2) that the material created by these artists and the way that they’re received differs from person to person; for instance, the scope of what they refer to as “noise” varies drastically across the board.

But most importantly, the film identifies a number of women involved in creating this music, which makes the notion of male dominance feel skewed. Not only does it feature the likes of Valerie Martino and Nancy Garcia, who talk passionately about their craft, but it also tackles questions concerning aptitude, aesthetics, and the social repercussions of working in such a field. There is even a chapter called “Parents,” where the artists divulge what their folks think about the music they play and the environments in which it’s created. The pinnacle moment, however, comes during a short dialogue with Heather Young from Social Junk, who says that while it’s cool to appreciate a woman operating in what’s referred to as a “heavily male-dominated scene,” it’s not cool just because the performer is a woman.

I went back to this documentary five years after it was made, because 2013 has seen a great deal of coverage about women working in experimental music (a hideously vague descriptor that “noise” almost certainly slots into). My aim here is to explore how things might have shifted since then by focusing on some of the most captivating material from this year and looking at the role that gender might have played in that. Young’s point — that gender may shape both the work in question and our admiration of it, but does not dictate its form — is a fascinating one, and as a reaction to critical responses that have since veered substantially from Young’s observation, I want to elaborate on this point in detail by looking at four musicians — Pharmakon, Ashley Paul, Okkyung Lee, and Unicorn Hard-On — who have released exceptional material over the last 12 months.

There are of course pitfalls in emphasizing that gender is not the main driving force in appreciation, only then to discuss the work of four artists who are all female. But the musicians I have chosen more or less reflect our taste at TMT, and after creating some of the most essential music of the year, they should be supported for what they do, as opposed to being categorized because of their gender.

Gender Politics and Noise: Pharmakon, Nina Kraviz, and social discomfort

Pharmakon (photo by Justin Snow)

Pharmakon (photo by Justin Snow)

The definition of “noise” is subject to change over time, because it’s a descriptor for subjective sensation. Outside of a music context, it might be understood as being typically disagreeable, something that causes a nuisance or varying degrees of aural distress. But public acceptance and interaction with noise alters depending on the environment in which it’s encountered. In a musical setting, it’s all about taking those attributes and expanding the boundaries of the listener’s expectation, i.e., distorting what they might otherwise find undesirable or uncomfortable. There are of course distinctions to be made within the resulting embodiment, which can vary substantially — harsh noise vs. noisetech, for instance — and though each type has a similar aim, it depends on the artist’s stylistic preferences and the context in which they wish to project or manipulate those feelings of discomfort.

That could explain why a “noise scene” is often referred to in public discourse. Noise is regularly presented as a subgenre of music that spans everything from electronic to classical and that’s sought out by a minority group of listeners. Because electronic-based noise — such as Puce Mary, Cremation Lily, and Kevin Drumm — is generally aggressive in content, it plays into a bizarre stereotype about what women are interested in, which then feeds into the technical aspects of how that sound is engineered. The fact that electronically produced noise usually requires some technical know-how and can involve aspects of engineering are what transform that dated perception about female performers into a latching-on point for listeners. It’s always fun to see stereotypes being smashed to bits, but to make assumptions about capability that are based on gender is a common faux pas, which sadly continues to this day. (Boyle’s documentary is a brilliant example of how those stereotypes are pulled apart.)

So why is it, then, that when an artist such as Pharmakon releases an album, the first thing that is commented on is the fact that Margaret Chardiet is a woman making noise? This has happened time and time again this year in various commentaries (I’m not naming names), which kept bringing me back to Young’s observation: what’s important first and foremost is the art that is being created. Of course, Chardiet is working in a supposedly male-dominated scene, but her music isn’t dictated by the fact that she is female. In discussing DJ Nina Kraviz and the Resident Adviser debacle from earlier this year, where Kraviz was interviewed in her hotel room while taking a bath, Meoko says that “if you hear her music without knowing what she is like physically, her sex and her looks are the last thing that spring to mind.” Although these artists couldn’t be further apart stylistically, the same logic could be applied here, bearing in mind that vocals could be manipulated, sampled, or coming from a contributor. Pharmakon’s music is exceptionally compelling, and it’s the primary reason she’s so highly regarded. The fact that she is a woman is critical to how she approaches her subject matter, but it does not dictate the trajectory of her sound or her potential as an artist.

In a high-profile interview from earlier this year, Chardiet was asked what it’s like to be a woman in a male-dominated scene. Her response is one of the central reasons for writing this article. “It’s really not something I think about much. There have been women making noise since the 80s. It’s a male-dominated scene but not more so than any other scene. […] If the only thing you can grasp from it is something so superficial as the fact that I’m a woman making noise, that suggests to me that you’re not listening very carefully.” And indeed, the biggest pull factor for the Pharmakon sound is that it’s technically stunning. Chardiet has been able to channel deeply personal sentiments through a stark and emotionally rupturing aesthetic. What makes her a remarkable artist is not just the ability to naturally contort and test vocal limitation, but her exposure of social observations, which are distorted in a way that allows her to feel as though she is making a difference. And she is: her music is provocative to the point that it derails most other attempts at creating social discomfort, not because she is female, but because she is incredibly talented and has the deftness to create these harrowing pieces. The resulting music fits into a category that’s founded on power electronics and dark ambient textures, but it’s her technical prowess in stitching it all together that gives Abandon its deliciously potent kick.

As per the album cover, the music on Abandon comes from personal experiences, which are unique to Chardiet as an individual. In this respect, her gender is an essential component to the make up of her sound, but it should not be used as a means of judging her talent. It’s abhorrent when those factors are used to make prior judgment about a recording or the way that the artist sounds, and it happens regularly. This isn’t limited to music that pulls on harsh noise aesthetics, though. Indeed, it follows nicely that Chardiet’s comment about male dominance ties into the smokey consensus on GUTTER — it’s not only felt in noise, but also in hip-hop, metal, jazz, blues, d&b etc. Noise has the potential to borrow from each of these genres differently, and it’s curious to map how the resulting works can be remolded to suit an alternate context.

Beating the Boundaries: Ashley Paul’s explorations in acoustic pitch

Ashley Paul

Ashley Paul

Earlier this year, former Yellow Swans member Pete Swanson re-imagined a track called “Soak the Ocean” by Brooklyn-based artist Ashley Paul. In his description of her live performance, Swanson said that “Ashley played a clarinet […] and focused on emitting long high-pitched tones that seemed to make the most hardened noise guys’ hair stand up on the back of their necks.” He also quoted Keith Fullerton Whitman as saying of Paul, “I’ve seen her play these harsh noise shows where she’s the only woman playing. She walks up on stage with only a clarinet and manages to lay waste to all the guys riding the feedback wave.” Aside from being struck as to how both artists felt the need to bring gender into the equation, their description of her music appeared to allow ample preparation for what one of Paul’s records might sound like.

But when I first heard Line The Clouds, I was utterly taken aback. Paul is classically trained, but she spent a long time working with various forms of jazz before exploring avant-garde composition. Her style hinges on emanating high pitches and spine-tingling tones, which she kindles through saxophone, bells, guitar, and bowed crotales. The resultant sound could not be further from the damning coarseness of harsh noise or the guttural snarl of Pharmakon’s PE endeavors, but it has the potential to induce a similar response. Paul’s music is wonderfully enchanting and quite unlike anything else that’s been released this year; there is a feeling in the songwriting that’s grounded on the most subtle observations, which are caught up in free-form acoustic improvisation and experimentation.

When I spoke with Paul back in June, we talked about what it was like performing at festivals and the kind of acts she often gets billed with. She told me that most of the time she feels like the odd one out, but only because her music is so different to what anybody else is playing. Line The Clouds is a sublime listening experience because of the directions it takes you in and the way that it makes you feel — it catches you unawares, with an isolating quality that’s difficult to embrace, as each sound is so subdued and delicate. Whereas harsh noise has the potential to dominate the listener through aggressive sonic structures, making it easier to zone out to, Line The Clouds leads to a very private space that’s sensationally jarring.

In this respect, I’m doubtful as to whether Paul would be happy with her work discussed in the context of noise, but it feels appropriate because of the reaction it conjures as opposed to how it might conform to a specific label. For that reason, it’s a perfect example of how music is directed by artistry, which pulls on an abundance of visceral responses that have little to do with gender.

Okkyung Lee: I Make Noise

Okkyung Lee (photo by Nathan Thomas at Fluid Radio)

Okkyung Lee (photo by Nathan Thomas at Fluid Radio)

The role of acoustic instrumentation in noise is fascinating, and there have been a number of albums in 2013 that have had an impact (though admittedly not in the same way as Paul’s). Okkyung Lee has to be one of the most prolific artists working in that domain right now. Not only has she released full-lengths on John Zorn’s Tzadik and Stephen O’Malley’s Ideologic Organ, but she has also worked with Marina Rosenfeld and C. Spencer Yeh, played gigs with members of The Necks, and collaborated extensively with Lasse Marhaug, who recorded the aforementioned album using a secondhand cassette recorder.

The latter album might have taken a long time to sink in, but Lee is an astounding artist dedicated to breaking down the boundaries of composition through her use of acoustic strings and abstract recordings. She is certainly proud of her direction — “I make noise” reads the description on her Twitter profile, which is certainly an apt way of recounting her approach. Lee used Ghil as a vehicle for detailing her relationship with an instrument she has grown up with and a city she is apparently most fond of. It sounds like an improvised cluttering of strings and vibrations that twist and snarl, testing the dexterity of their material compounds.

But in describing it, I’m already playing into the reason that led her to retain a fair distance at first. Lee mentioned this in an interview with Fluid Radio, saying “It would be great if people could listen to my music without any preconceived notion of what it should be, […] but then that’s also impossible, not to have any kind of idea what you’re getting into.” In the same interview, the author expresses their preference for a review of Ghil written by a four-year-old girl, who was not given any information about the album or the instruments or any context whatsoever, including the artist’s gender. Without this information, the young girl depicted a series of reactions to what she heard without once referring to any additional factors, a complete detachment from the trappings of any press release or social construct. When I wrote about the record over the summer, I found that there was too much weight attached to the external elements of the music, and that got in the way of how I was able to access these sounds. The Search and Restore review is particularly significant, because it emphasizes just how powerful Lee’s work can be while holding its own weight. Lee might be a woman working with noise, but her material is so far detached from identity politics that additional emphasis on her gender seems ridiculous.

Noise in a physical domain: Unicorn Hard-On and the Laundry Room Squelchers

Unicorn Hard-On

Unicorn Hard-On

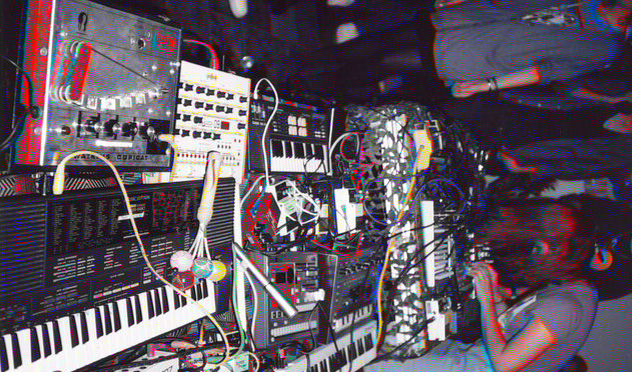

As gender played a role in the title of Boyle’s film, it also plays a role in the way that art is perceived when it’s created by practitioners who do not conform to the “male-dominant” stereotype — that’s just inevitable. The importance, however, lies in its appropriation. Perhaps GUTTER struck a particular chord with this writer, because it also features Valerie Martino, whose debut album as Unicorn Hard-On was released in September by Spectrum Spools.

For over a decade, Martino has been working on her own unique breed of noise-infused techno, and Weird Universe feels like a refined consolidation of her sound on a single disc. But her music doesn’t stop at Unicorn Hard-On. As part of Rat Bastard’s improv noise collective, the Laundry Room Squelchers, Martino takes part as one of several performers who are encouraged to go completely berserk during performances. This involves provoking the audience to participate in a no-holds-barred human pile-up throughout the set. Due to the physical nature of her work and the role that she plays in that collective, Martino also defies any stereotypes about female musicians through the way that she uses her body — that savage black eye is perhaps the most well-known consequence.

But these stereotypes have eroded over time, in part because they were never based on fact or even a reliable premise. Instead, they were formed through social constructs and expectations about what it means to be a woman in the music industry, which is frequently criticized as being regulated by men. Of the four artists I have discussed here, Martino is the essential antidote to this, not only in the performance art she creates as a Squelcher, but also in the corporeal nature of her approach and how that plays into her music. The Squelchers’ rumble is what led to the trophy display of bruises at the beginning of GUTTER, of performers so immersed in their sound that they come away wounded. Weird Universe is an embodiment of that physicality, which is strenuous but powerful, a sonic embodiment of how the stereotype is gradually dissolving.

Conclusion: Sexism and all similar bullshit must die

The disparaging comments that see gender taking a precedence over artistry need to stop. Not only are these artists operating individually in a way that challenges audience and critic perception alike, but they have also contributed to breaking down a number of stereotypes about people and noise, about expectation and appreciation. In terms of online coverage, it appears there has been more exposure of female practitioners this year, but again that’s only a perception, one that’s easily warped by the social media and familiar web haunts that become a part of some idiosyncratic online routine. The crucial thing is that it has been a great year for noise in all its variant forms, and that’s the point that needs to be emphasized above everything else.

The final quote from that Meoko article comes from Nina Kraviz herself, who despite not fitting remotely into the aforementioned noise categories, hits the nail on the head in the crudest terms possible: “Sexism and all similar bullshit must die. And the first step to it is to let artists be who they are regardless of their gender, skin colour or sexual orientation.” Here’s to all that’s set to follow.

We celebrate the end of the year the only way we know how: through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music and films that helped define the year. More from this series