Anybody seen a knight pass this way?

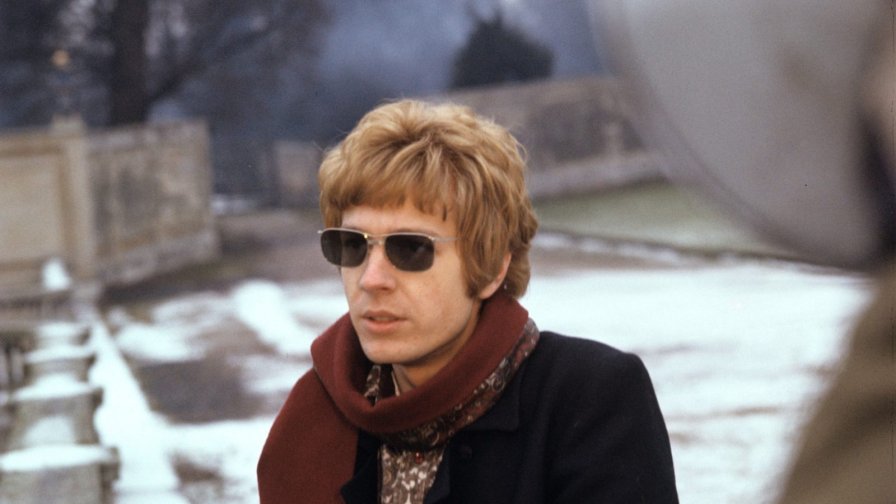

Scott Walker’s death is a tremendous loss to music’s future. You can read all about his storied career history in countless publications right now, and no doubt there will be books to come, interesting reads that contextualize the shifts and leaps that Walker traced in the sequence of his work. You’ll hear about his early successes as a teen idol and crooner, a slump into a drink- and drug-addled middle period, an opaque but momentous late-period dive into the avant-garde. We tell the stories of people when they die, in part because their stories have in some sense finally finished and in part because death triggers memory. And then, slowly, the figures fade from public view, no matter how greatly we as individuals continue to prize their works in private. The context rarely arises again, except of course for anniversaries, which is when we’ll trot out the same remembrances, remark on legacies and time-tests passed, reveal hidden details some have forgotten or never knew or ignored, place the work in and against the new contemporaries, open the floor again to public comment.

But Scott Walker’s work resists this sort of easier memorializing. His late-period works, especially the trilogy of Tilt, The Drift, and Bish Bosch, represent not just moments in an artist’s lifetime or examples of capable craftsmanship, but enduring innovations on the song as form, profound explorations of the possibilities of mood and lyric, revelations of brutality and humanity across a multiplicity of time spectra, an extension of the limits of language into spaces between comprehension and senselessness. This is not an exploration of Walker’s interesting life (a life that he kept mostly private and that no doubt held much more than music), but an incomplete and fragmentary record of his achievements, in hope that the discussion surrounding his work continues beyond his physical ending, that the future has more to gain from the piercing sonic light he filtered through the blackened glass of history.

The Song-Form Revaluated

Many chronologies trace the beginning of Walker’s avant-garde turn to “The Electrician,” from the resurrected Walker Brothers’ Nite Flights. The song is about a CIA torturer delighting in the knowledge that at any moment he could kill his victim. Opening with taut, unresolving strings over a menacing, single-note bass line, the song moves from a disquieting verse about the lights going low to a transcendent, joyous chorus: “If I jerk the handle/ You’ll die in your dreams/ If I jerk the handle, jerk the handle/ You’ll thrill me and thrill me and thrill me.” Romantic strings fill the bridge, melodies that wouldn’t feel out of place in a schlocky musical, before the tense verse returns.

Structurally, the song violates pop expectations, its verse-chorus-bridge-verse leaving the listener unfulfilled, desirous of another horrible chorus and its elevated violence. Walker’s sublation of love-song precedents echoes through the lyrics, as the titular electrician revels in the thrills his victim makes available to him, the thrills that his position simultaneously enables and abjures. The rock love song often mistakes narcissism for romance, evincing so much concern for how the speaker feels without any evidence of an empathetic link with the object of love. “The Electrician” laid bare the violence of the love-song idiom using its own tools against it: the unfulfilled verses turned malevolent, aching for the chorus’ traversal of the fantasy of violence; the violent and acquisitive imagery caked in manipulative, uplifting melody; the presence of the other as a mere tool for erotic, violent pleasure. And what questions does it raise about the US’s history of violence, its way of packaging its missions of acquisition as a desire to offer the colonial other their freedom?

Following “The Electrician” and its formal innovations, it’s telling that the late trilogy begins with Walker’s most masterful imagining of a classic song-form, Tilt’s beautiful elegy “Farmer in the City (Remembering Pasolini).” Written on the death of Pier Paolo Pasolini, it is Walker’s greatest work of tragedy, a masterwork portrait dripping with the pain of loss and memory, yet suffused with the alienation of modernity. “Farmer in the City” is the link that connects Walker’s trilogy to the canon of song that stretched before him. Like few others in the late work, the song exerts its transcendent longing through melodic glory, rising action and climax, profoundly crestfallen lyrics: “Hey, Ninetto/ Remember that dream?/ We talked about it so many times.” It explores the life of Pasolini through the lens of the classic fish-out-of-water story: Pasolini the uncompromising auteur as a farmer lost in the marketplace, searching for purchase in a world that rejects him and the one he loves, and the violence of his murder, all that it cut off for the world. Much like “The Electrician,” it ends on an unresolved, disquieting refrain, opening into the radically hypermodern “The Cockfighter.” “Farmer in the City” is the Janus face that connects the past and the future of song, a final look over the shoulder at what once was and a look forward with dread at what must now be.

What follows, then, is an unfettered restructuring of song into twisted, neologic forms. Where for “The Electrician” Walker employed and twisted classic love-song structures, The Drift’s sprawling second track “Clara” would see him shatter those structures into oblivion, colliding cinematics of secret, midnight trysts with newsreels of the hanging bodies of Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci. Walker inhabits Petacci’s doomed, self-destructive love for the dictator, raking her across moods of paranoiac nocturne, waves of aggressive violence, anxious post-coital pondering, bathetic oboe stabs against spacious emptiness. The sound of a man punching a slab of meat features prominently, a flat, heavy thump, evidence of Walker’s refusal to compromise on mood. An image of a swallow trapped in an attic, a corn husk doll dipped in blood, moonlight on the hanging bodies at dawn — these images recur and recombine, never allowing the listener to rest within a peaceful moment. It’s a fully postmodern Tristan and Iseult, where the lovers face constant interruptions by violence; a threatening, inescapable solitude; and the final indignity of the defilement of their executed bodies in a public square.

If “The Electrician” is Walker’s critique of the love-song, “Clara” is his explosion of its possibility. Where “The Electrician” lacked empathy, here Walker extended it past its limits, forcing the listener through Petacci’s rapid mood shifts and relentless, deepening distress, discovering not a climactic, transcendent chorus but an empty, horrific anticlimax. It grants us access to the humanity of a monstrous love and steeps us in the self-destructive allure of power and terror. In the search for the safety and peace of love, we find through “Clara” only danger and violence. With “Clara,” Walker used the love-song, its permutations and inversions, to open an inhospitable world for the listener’s temporary inhabitation, yet never allowing us to forget that, in doing so, in gazing into this abyss, we must become the monsters.

Atemporal Fusion and Perspectival Collision

Walker didn’t write songs about himself and his troubles and triumphs. Instead, he inhabited characters, often in multiple, consciously merging their perspectives, shifting in and out of their words and visions, linking them together across time and space. Tilt’s “The Cockfighter” links Adolf Eichmann and Queen Caroline of Brunswick and a dying rooster with the infinite starry spaces above, exploding out of the spacious lull that opens after the final call of the auctioneer in “Farmer in the City.” Elvis’s stillborn twin brother mutates into a 9/11 victim on The Drift’s “Jesse,” with Elvis lamenting at the end: “I’m the only one left alive.” Soused, Walker’s collaboration with Sunn O))), features “Herod 2014,” which bridges gaps between the massacre of the innocents and a woman’s murder of her own children in her attempt to protect them from horrors of the world. In “SDSS14+ 13B (Zercon, a Flagpole Sitter)” from 2012’s Bish Bosch, one can follow Zercon, Attila the Hun’s noseless jester, moving through history to mock Christian stylites, to merge into Wagner’s Ring Cycle, and to sit so long at the top of a greased flagpole launching insults into the void that he becomes SDSS14+ 13B, a dead star floating in endless solitude in the emptiness of space. The terror and beauty of “Cossacks are charging in, charging through the fields of white roses” yields to George W.’s stupid joke about meeting his French counterpart: “I’m looking for a good cowboy.”

This technique of colliding perspectives and splaying the results across a distended historical backdrop enabled Walker to critique contemporary motions through singular perspectives, contextualizing the absurd present against the absurdities of history. It strains against the necessity that music be bound to time, that poetry be bound to perspective, and it works to reconstitute new song-forms out of the fragments of time and perspective that juxtapose against and merge into one another. Walker’s voice becomes the only consistent element even as he adopted the protean temporal and personality drifts of the lyrics, his mournful baritone recognizable everywhere throughout his work (excepting the infamous “Donald Duck” passages of the end of “The Escape”). It’s that tension between the amorphousness of his lyrical subjects and the utter singularity of his voice that fuses the listener into inhabiting the odd spaces of history and darkened passages of identity that Walker explored; without his voice as a sturdy anchor, we would drift into the cosmic mess, unmoored.

Limits of Comprehension

Absurdism is not a recent development, but Walker’s later works stretched beyond the merely absurd and into a space that touches both the comprehensible and the opaque, where meaning slides across sense-making words and fragments, only to pale in their concatenations. Take these lyrics from Bish Bosch’s “Epizootics!”:

Blip boost bust brother

That’s how we copped a final

Reached this city without sound

Everywhere you turn

Bunkers of rubber hoses pronging up off the city’s floor

Chirp chime clambaked cups

Don’t step on that rotting tartare

Just might bust your conk

Might lay your racket

Early black ickaroo

Here, Walker pulled words and phrases from Cab Calloway’s Hepster’s Dictionary, without which the lyrics seem fruitless — an ickaroo, for instance, is someone who can’t dance, and cups is sleep, copping a final is going home. Behind the top layer, another language speaks, but even with that knowledge, the assemblage of the lyrics still evokes absurd images — rotting boeuf tartare, for instance, on the dancefloor. These lyrics float over ridiculous jazz sonics, cluing us into the hipster slang precedents and creating a context for the blasts of absurdity. There are likely metaphors this interpretation is missing, and Walker made few attempts at resolving the opacity of his lyrics. What we are given then is an opportunity: noticing the the coded language recommends further stabs at comprehension and leads the listener deeper into sense-making possibilities. Whether Walker had in mind a true interpretation is irrelevant. Instead, he invites the listener into a space of both challenge and surrender, tantalizing with puzzling details, offering clues while closing off certainty. This tension dangles an offered reward of understanding while also withholding it, and thus understanding is always out of reach, rendering Walker’s late songs both inexhaustible and exhausting.

There is a tendency to give up on interpretation of Walker’s work, whether out of frustration or exhaustion or even the suspicion that nothing hides behind the opaque wall of language. But there is another possibility: Walker’s lyrics are open, even where they are concrete and nailed down. They invite the listener to experience their evocations, while experience, comprehension, and surrender interpenetrate and yield up a kind of mass of meaning. Walker’s preservation of the comprehensible narrows the scope of interpretation, and it’s clear that he invests each moment of song with significance, but their connectedness, the tissue of the song taken as a whole, is an open accretion of these significant moments, reaching into multitudes of interpretations. “Cue,” the centerpiece of The Drift, famously took him 9 years to write, and it is also famously very difficult to comprehend, with few clues from Walker’s rare interviews to assist. When he did speak of it, he apologized for its impenetrability, but believes it to be one of his most successful lyrics. From an interview with Elsewhere, September 16, 2008:

That was the one that took the longest time. It started as one thing then became a personal song in the sense of Self, not ego-self or knowable-self but in the way of whatever the Self is. It’s a very, very difficult song and I just hope that when people look at it they see that it has the rhythm in the lyric and the rhythm otherwise that will carry it along, because it was really tough.

But what I also say is, if you interpret the song that’s fine. I like whoever the audience is to interpret my songs because maybe nine times out of ten they’ve got a better interpretation than I do, and that’s important as well because then they become a part of it.

Disease, the body, death, music — each of these concepts weave into the lyrics of the song, generating a cloud of sense, while other sequences oppress as onomatopoeia (BAM BAM BAM BAM) or an impossible nonsense (tell me, what are “jigger raps pits”?). Floating in the open space of the music, these elements fuse together into an utterly unique experience, an open structure simultaneously full of rational and aesthetic meaning and yet also transcending the light of rationality into the darkness of the open sky.

Sound, Space, Silence

Much of this discussion has focused on Walker’s uncanny lyrics and novel structures, but his achievements also lie in the realm of composition. Walker’s sense of theory, although apparently mostly self-taught, enabled him to weave moods and spaces that are rarely experienced in other musical works. A mastery of tonality, rock instrumentation, and string arrangement gave Walker the tools to craft wrenching emotionality and unbreakable tension, while a deeper sense of timbre and space led him to seek out novel sounds, placing them within a context with traditional instrumentation to craft novel soundworlds. Some moments require heavy percussion, such as the endless pummeling on “‘See You Don’t Bump His Head’” or the driving kit on “Cossacks Are.” Others demand beatless texture, jarring stabs from the sudden entrance of new instrumentation (take, for example, the endless variety on “Corps De Blah,” the slicing machetes on “Tar,” or the odd empty spaces of “Buzzers,” with little but a glass bottle, a few notes of guitar, and Walker’s voice). And, amidst all this heavy meaning and high art analysis, let’s not forget Walker’s sense of humor, his use of sounds that shatter the heavy seriousness and dramatic gesture with absurd hilarity: the fart sounds, the Donald Duck voice, the sudden oboes and contrabassoons, the harsh noise walls. For Walker, there was a sound for every moment, and the lyrics arranged them in ideal sequence.

In a 2013 interview with Stuart Maconie, Walker states that “silence is where everything starts from, it’s the basis of everything.” Far from the wall of sound and space-filling of his earlier work, the later work is often so spacious it feels as if Walker is trespassing against silence, filling only as little space as he needs, contextualizing his sounds within the great, yawning void of silence for a brief time until he retreats back into it, into the extensive space between his releases. I suspect that much of the disquiet that listeners experience derives from the vastness of space and the preservation of silence in Walker’s recordings. In music, we’re accustomed to sound filling all space, and reverb tends to offer mere after-effects to the sound, a secondary thought that improves the mix or deepens the harmonics. Whereas for Walker, spaciousness and the play between silence and sound is inherent to the composition. We thus hear a variety of sounds, but mostly Walker’s unmistakable voice, suspended within a vast environment, a human song against an empty cosmos, the song but a brief moment of triumph against it, a small but spectacular triumph of structure against emptiness, of life against the vastness of spacetime, of art against death.

This is woefully incomplete, but that is by design. I haven’t even touched the early work, which is excellent even when lacking the seriousness and artfulness of the later work. And there are many moments worth discussing on Climate of Hunter, much more to Nite Flights than “The Electrician,” and a great deal of artfulness in the numbered solo albums. I didn’t want to write a retrospective or to cover his entire history. I didn’t want to write a piece that talked about how Scott Walker is gone, in part because I still feel that he had more to say, that his late work was expansive and growing, and in part because remembrance pieces rarely focus on the actual work. With Walker, that was always the focus of his engagement with the media: the music, the elements that he composed to create it, the meaning and interpretation of the work, his desire for the audience to experience and enjoy it. I want to believe that this process isn’t finished, that there is still much to gain from Walker’s unfettered imagination and consummate mastery, that the reviews, even the most excellent ones, were not the end of the story. I eagerly await the works to come on Walker’s music and the works he inspires in the future of music, even if he can lend his voice to no more. There’s so much to unpack, inexhaustible troves of experience still awaiting discovery in his oeuvre. Even in writing this, I’ve found spaces I’d passed through before in carelessness, wide vistas of poetry, caverns of rich sonic texture, links and connections across Walker’s immense aesthetic aeon.

The night before the news of Scott Walker’s death reached the media, I was listening to music with friends. The playlist ended, but as our conversations continued, I heard a voice, horns, a strumming guitar. I couldn’t tell where it was coming from, and I fiddled with my device to find that Scott 4 had mysteriously begun playing, some glitch in my music player. It was, of course, “The Seventh Seal,” Walker’s mid-period exploration of death through the plot of the famous Bergman film. In the morning, I would find that he was gone, and an eerie silence crept into the room as I read the reports. I’m loath to attribute this to some spiritual sign — Walker had died days before — but something vast seemed to open where the immensity of his loss could be felt. His chess game had ended. The knight had strategized against infinity, fought off the darkness, held strong against the void of silence; but in the end, death comes for us all.

The knight his squire and friends, their hands held as one

Solemnly danced toward the dawn

His hourglass in his hand, his scythe by his side

The master Death, he leads them on

The rain will wash away the tears from their faces

And as the thunder cracked, they were gone

More about: Scott Walker