Every so often, a movie’s gotta lord it over. Despite all the birdshit spurious CHY (where “Do It” in DIY is conveniently supplanted with “Conceive in Hindsight”) comment factories hovering around our strangled dream machine, one can still easily sense an audience’s simmering ache to be properly ushered into an externally ordained state of mind. That takes a good story and shrewd technical acumen, but a sort of pitch man is what’s needed. And when this is done well, CHY-ers will increasingly rush to call it “overacting.” You take away personal preference, and a lot of what gets called scenery chewing is actually something grander. Scent of a Woman or Devil’s Advocate may not be the best movies, but when Pacino’s on, you are under his spell. Naturally, the same goes for countless actors. Whether you are invested in the story or not, they are wresting you from your disinclination with their magnetism. They lead, even in a supporting role, and still manage to keep their proper place in the story.

When a musician shows up in a movie, it’s often disastrous. Look no further than Sinatra all but ring-a-ding-dinging his way through the otherwise solid Manchurian Candidate, Mick Jagger in the irredeemably dopey Freejack, or Paul Simon shambling and mumbling about in One Trick Pony for examples. It wasn’t that David Bowie had a well-established image that made him one of the best screen presences going, and it’s not just his control and attention to detail around said image either. What made the camera, and us in turn, love Bowie was his never ending sense of play. There’s the timbre of his voice, the slight frame and piercing eyes, but he stretched beyond these qualities in a way that suggests a restless, hungry soul. It’s an eagerness that’s in all of us, and when we see it glinting on a fine-tuned performance, it’s easy to find ourselves swooning like daffodils.

Before getting into some examples of this, it’s important to establish what the man was up against. Not only are there scarily talented impresarios like Denis Lavant to make you look bad, but you have a musical repertoire so ubiquitous as to be an inspiration to these giants. So Bowie wasn’t just standing in the shadows of great actors, but his own (already cinematic) renown. Bowie would’ve been forgiven for going the route of other rock stars, doing a winking turn for the fans, but he acted with the commitment of one who had nothing to fall back on. As others have pointed out, he rather folded his musical efforts into his work, much like Lavant (and director Leos Carax) did with “Modern Love.” The song, the tracking shot and Lavant’s tortured limping morphing into a leaping charge all fuse together for a moment so ecstatic and wild that it nearly eclipses the rest of the film (and certainly the vid Bowie had running for it on MTV). As with Inglourious Basterds (Firestorm, maybe not so much) and “Cat People,” both the film and the song are suddenly brighter in each other’s presence. What’s extraordinary is how small Bowie managed to make himself despite this power.

That is to say, he resonates in turns of all sizes. Be it brooding, mercurial Nikola Tesla or the deranged, dimensionally snagged Agent Jeffries in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, his characters feel inextricable from their surroundings. One senses a great sensitivity in his film work, one rarely met with self-consciousness. Even in tights, teased hair, a mascara twirling, and a crystal ball around a bunch of puppets, there is a lived-in, endearing quality cooling us out. At every mocking “oh those eighties” snarkathon sesh about Labyrinth, there is a twinge of the notion that Bowie’s dry, perfectly pitched performance (and catchy songs) hold a lot more sway than that batch (admittedly a questionable choice, and the goblin’s heads are right there like it’s a microphone or something). What would’ve been a throwaway role in even a seasoned actor’s hands is rendered strikingly enough to help make the film a fantasy staple.

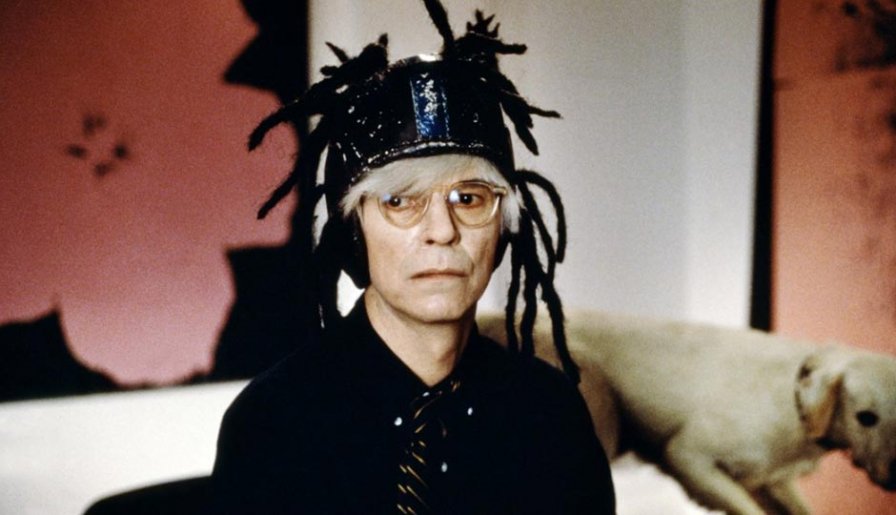

Julian Schnabel must’ve known the story of when Bowie met Andy Warhol when casting his 1996 biopic, Basquiat. Apparently the two didn’t have much chemistry and Warhol was decidedly disenchanted with Hunky Dory’s eponymous tribute song. As to whether or not Bowie drew from his experience in his portrayal of his hero is unclear, as it is an affected yet sympathetic portrait. Some have criticized it as silly to the point of caricature, but there is plenty of nuance. If you overreact to his well-documented whimsy, it’s easy to miss the tenderness and steady, clear-eyed perseverance. Andy may not have been able to help Jean-Michel, but the film uncloyingly suggests (aided by Bowie and lead Jeffrey Wright’s natural gifts for understatement) the steadying effect Warhol had on the troubled painter. At a glance, it’s easy to see where the critics were coming from, but Bowie’s Warhol is funny for what he says and the unassuming way in which he says it. The eccentricities aren’t fodder, so much as rudimentary shadings of the world he’s built for himself. Bowie may have failed to mind-meld with the artist, but thanks to a sensitive script, he gave us a Warhol that’s grounded without losing the mystique.

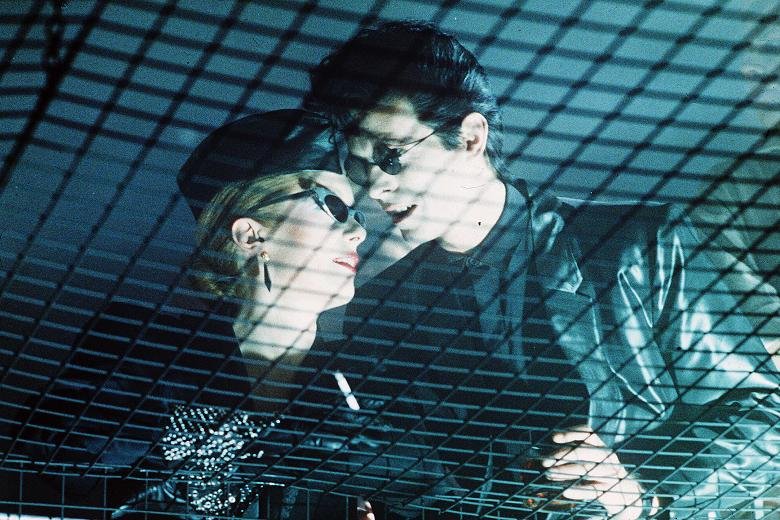

As much as one tries, Tony Scott’s (Ridley’s little brother) The Hunger never quite plays as well as it does in our minds. But Bowie is present and frost bite-inducing as a vampire doomed to age rapidly short of immortality. Old age make-up is usually the pits, and while that stands here, Bowie’s meticulously pitiful physicality (a glimpse of his gifts with mime, perhaps best displayed in his Broadway portrayal of John Merrick) almost makes up for the sluggish pacing. That and the hyper-saturated, urban gothic atmosphere. The colors you see when you close your eyes and blast “Station to Station” (cobalt blue, off-black, flourescent whites and reds) are flooding this thing. Its two plus hours don’t hang together all that well, but it could take on a new life if one were to put on S2S and watch those long loft/hospital shadows, Grandpa Bowie and Catherine Deneuve hooking up with Susan Sarandon on mute.

The same year Bowie ran the gauntlet as a prisoner of war in Nagisa Ôshima’s grueling battle of wills (stated and not quite), Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. His character endures endless abuse at the hands of Sgt. Gengo Hara and unrequited advances at the hands of Capt. Yonoi (fellow musical trendsetter, Ryuichi Sakamoto). In full on Serious Moonlight mode, Bowie is both taciturn soldier and golden aura. Takeshi Kitano (playing the brutal Sgt. Hara) isn’t just a test to this character’s virtue, but to Bowie’s screen presence as well. Takeshi’s flat, randomly twitchy visage is the stuff of film legend, and he plays the antagonist with a predatory calm that had to have spurred the less seasoned actor to new levels of expression. Merry Christmas is a subtler, richer film than The Hunger, yet they equally highlight Bowie’s sly dexterity and keen collaborative instinct. He is arguably the biggest name in both, but he selflessly buries himself in the story at hand.

Here was a rock god-turned-actor that managed to both respectfully defer to, yet acquit himself from all the trappings of the auteurs of his time (Roeg, Scorcese, Henson, Landis). His Pontius Pilate is predictably droll, but his brief display of calmly sinister conviction puts Last Temptation of Christ’s talking snake satan to shame. Perhaps Bowie should’ve been in Martin Scorcese’s After Hours, as his straight-on malevolent turn is one of the few things that makes the similarly plotted night-from-hell farce, Into The Night, memorable. Both are 1985 films, which makes it seem like Scorcese and John Landis were in some kind of competition along with offbeat leads Jeff Goldblum and Griffin Dunne. Bowie acquits himself as best as one can in a tonally uneven, “edgy” misadventure, but his material is thin beyond a cute moment where he makes Goldblum fellate his firearm on a street corner.

While it’s undeniable Bowie’s most essential effort went into his songs, he still had enough inspiration left to make a substantial cinematic mark. And this argument will ever rest on The Man Who Fell to Earth. It’s easy to imagine Nicholas Roeg working with Donald Cammel on 1970’s Mick Jagger-starring Performance and putting the pieces together for his own art/rock amalgam, but Roeg came to Bowie organically, years later. Watching him hang out Don’t Look Back-style in a BBC doc (1973’s Cracked Actor), he knew he had his Thomas Jerome Newton. As much a victory lap as a great film, Roeg was coming off the sleeper success of bizarre horror/drama Don’t Look Now (mostly due to an infamous sex scene between Julee Christie and Donald Sutherland) and his stunning Palme d’Or nominated debut Walkabout. With his now-trademark, disorientingly non-linear editing in place, The Man Who Fell to Earth shows a director with great ideas playing fast and loose. His determination to get the pop star to come bracingly alive on screen comes through, just as his dressing down of the honey voiced Art Garfunkel is perfectly articulated in his follow-up (and arguably last great film), Bad Timing.

Bowie was serious, but not above acknowledging that to many his presence in a film is foremost a novelty (see: Zoolander). Tragically, his continued ubiquity may’ve kept the actor from disappearing into films the way he only began to show us he could’ve. But one can watch Roger Daltrey, Sting, or (god forbid) Meat Loaf in something and easily see how wobbly the transition from stage presence to narrative presence can go. Even a fractured narrative like Man Who Fell to Earth contains more than just a series of mystique-flattering tableaux, despite bearing a passing resemblance to some of Jagger’s more self-conscious, token work in Performance. These moments, in both cases, are simply confectionery regressions brought on by rebellious ephemera. Guns and especially cigarettes are the proud emblems of the fashionable nihilist in everyone. A ciggie and a firearm are and have always been reliable props for actors with all ranges of capability. Be their visual presence sacrosanct or glib, Bowie/Newton smoked like someone who got hooked when he realized it was a nervous gesture refinement that neatly met his aesthetic ideal. But unlike Jagger, Bowie elevated these tired props beyond basic delinquent contrariness.

Bowie’s voluminous alien ricochets through sour disaffection, wonder, ruthlessness, vulnerability, tenderness, and something that the director and actor purposefully left inscrutable. It makes sense that Bowie took this character to heart in his main gig, as it was on this tenuously blotted paper stage that he seemed to paradoxically thrive the most. Both a source of light and the motion-lapse blur of a soul too stirred to take any point of view for granted, Bowie owned the screen before one even realized it was for sale. And as is the case with any unprecedented film phenomenon, we were happily taken.

More about: David Bowie