We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

60

Klein

Tommy

[Hyperdub; 2017]

Love & hip-hop: Atlanta — that’s, like, a reality TV show, right? Yes, and it’s also electronic artist Klein’s backstory for her debut album on Hyperdub. Beyond providing a title and a source for sound samples, the show’s bad-girl guest Tommie Lee served as an archetype of obstinance: “What would Tommie do,” Klein mused in an interview, “like, she wouldn’t even care.” Likewise, three albums into her own career, Klein showed little interest in playing sweet with the powers that be. Recorded primarily in her bedroom, Tommy was as volatile as its namesake’s reputation: gaseous piano chords looped over fractured beats, blasted by noise, then smeared into opaque drones. Whether crooning or chanting, Klein sang wordless alleluias chapeled in her body, riffing across scales with gospel exuberance. Produced with an ear for entropy, Tommy thrillingly bridged two separate worlds, the musique concrète tactics of Pierre Schaeffer’s avant-garde with the vocal prowess of Billboard R&B divas. But unlike her plaque-chasing peers, Klein has better sense to save her walls for family portraits. Real gold, as Klein well appreciates, can’t be won by committee vote. It doesn’t sparkle so brightly — or so easily.

59

Low

Double Negative

[Sub Pop; 2018]

On Double Negative, Low had successfully pulled off a feat few recording artists would’ve dared entertain for a 12th album in a 16-year-long career: they’d transposed the essence of what made their music different than anything that come before into a sound both fresh and contemporary. In Low’s case, what that meant was putting the bewitching vocal harmonies of founding members Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker through a metamorphic treatment of heavy digital processing, chopping and twisting and then ultimately placing them against an indescribable, half-instrumental, half-synthesized backdrop that clattered around as if molded from static alone. On the one hand, listening to the album was akin to discovering a decaying Disintegration Loops-like residue of a musical past, which was somewhat cheekily making the self-deprecating point of the datedness of Low’s world; on the other, Double Negative offered a blueprint for veteran artists whose spirit had not gotten old but whose expressions could use a facelift. More than anything, though, the album belonged: to Low’s awe-inspiring legacy, to a post-genre musical landscape, and to a world that increasingly felt like a disintegration loop itself.

58

Jam City

Classical Curves

[Night Slugs; 2012]

Classical Curves was the sound of a new world in the process of creation. Released in 2012, it thought through the emerging aesthetics and politics of the post-recession: a world in which decay was made structural, where collapse was folded into “growth.” It made visible the wreck of neoliberalism, its primal scene, endlessly repeated — buildings with pools and doormen in a state of constant tumescence, accompanied by homeless people round the corner, always kept out of sight. In Jam City’s native south London, Classical Curves sounded like “regeneration,” the flattening of specificity to make way for a verticalized generic. In its jackhammer beats, we heard the demolition of shopping centers, the exile of local communities, their making way for dull flats, lifeless gyms, and bad coffee. These losses wrapped themselves around Classical Curves, making themselves heard in its vocalic synths, their sighs the echoes of lost worlds. No mere exercise in late-capitalist fetishization, then, Classical Curves wanted to move us. It wanted to make us dance, and in so doing, it wanted to make us think. In its elegantly-shaped empty spaces, in the uncanny funk of its mechanized movements, and in its provision of a shape for pop to come, Classical Curves developed a sound that helped us understand where we came from and where we were going. This was how we related to our bodies, our clubs and our cities in the deadened hyperreal zones of the 2010s.

57

U.S. Girls

Half Free

[4AD; 2015]

Eight songs and a skit was all it took. Despite its brevity, Half Free felt enormous, genreless, miragelike. Its production hit a pleasingly foggy mid-fi sweet spot, overcast, suggestive, noirish — an appropriate objective correlative to the stories its songs contained, populated by dead soldiers’ widows, familial cruelties, and strained spouses, all told first-person. These were stories, all of them, about women wronged by men, or left behind by men, or contemplating vengeance upon men. The eight songs played around with as many genres, tied together by Meg Remy’s voice and almost country-esque command of sung storytelling. The heart of Half Free, though, wasn’t really a song at all. It was “Telephone Play No. 1,” the minute-long Rorschach blot of an interlude that stopped the album after two tracks. With each listen, it could reveal a new meaning, and yet it was the hardest thing on the album to listen to, the aural equivalent of the very bright light an optometrist shines into your pupil to look at the back wall of your eyeballs.

56

Triad God

黑社會 Triad

[Presto!?; 2019]

NXB, the full-length start to the partnership between London via China via Vietnam MC Vinh Ngan and experimental electronic pop producer Palmistry, had all the markings of the unique aural aesthetic the two would decide to stamp the name Triad God squarely on. It was 黑社會 Triad, however, following after seven years of near-radio silence from Ngan, that took that aesthetic and turned it into a sublime, unprecedented sound artifact of crushing immediateness and bewildering beauty. On 黑社會 Triad, Palmistry’s minimal synth melodies and deconstructed hip-hop beats dissolved into digitized operatic yowls and towering ambient vistas, while Ngan’s lethargic, mostly-Cantonese rapping became full-on confessional poetry, delivered via fragmented, half-awake monologues. As the album progressed, the two sources of sound and substance became increasingly desynchronized, to the point of their co-existence appearing less like music and more like a field recording of a very real, very painful moment in someone’s life. Listening to vignettes such as “So Pay La” felt like having your friend suddenly pour their heart out to you in the wee hours of a Sunday morning, when you’ve had way too much to drink and can’t wait for the person working the kebab stand to call out your name. You don’t understand half of what your friend is saying, but the gravity of the moment hits you just the same. And then you listen.

55

Drake

If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late

[Cash Money/OVO; 2015]

And, just like that, Napoleon crowned himself. Finally endowed with the heavy airplay (all day / with no chorus); laundry list of famous exes; and, well, bands that a young Aubrey had always flirted and fantasized and fronted about, Drake emerged on If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late as an a priori. No longer just my homie over there who think ur cute, the perpetual aspirant already unconvincingly flexing with Nickelus F on Room for Improvement, Drake could finally stop orbiting every possible influence, opportunity, and storyline and let his own tumid gravity constellate his place in the pop/rap cosmos. The self-styled (for how could it be otherwise?) 6 God looked good as a celestial body, his stardom as unassailable (though truly nothing was the same with dude after Sauce Walka ethered him — OOWEE!) as it was inaccessible. None of which is to say that Drake’s hard-won iconicity licensed empty simulation, the stuff of media studies undergrad dreams; if anything, If You’re Reading This demonstrated why Drake’s corpus of pastiche and reference, a seriously jacked body with seriously juiced organs seemingly cobbled together out of logos and other simulacra, commanded such fervent brand loyalty. On display in If You’re Reading This were Drake’s unmatched powers of curation and customer service, his perfectly calibrated sensitivity to the affective life of human capital in a rapidly and rabidly freelancing world pivoting to video. Because who else other than the internet’s busiest simp could demonstrate how performative disavowal is no match for the architectures of desire goading our most egregious and mundane fantasies? Sorry Jenny Holzer, Drake isn’t going to protect you from what you want. He is what you want. Oh, you gotta love it.

54

Jason Lescalleet

Songs About Nothing

[Erstwhile; 2012]

With its cheeky concept and punny track titles, one might be tempted to assign a type of theoretical gravity to Songs About Nothing, casting it as some high-level comedy of deconstruction. One might be impelled to hunt down traces, quaff some pharmakoi, and split the différance. And that’s all well and good. Discourses about appropriation, decontextualized sound as plastic, politics of pastiche and irony, metaphysics of presence, decay and deformation, being and not-being: each potentially generative avenues of exploration into Jason Lescalleet’s monumental work. However, we don’t need to distract ourselves with what is external — Songs About Nothing stood alone populating the void, in defiance even of its own title and network of samples, references, and appropriations. Great buzzing existential meatsaws scourged its 76 minutes and shred all stable signifiers within. Whether it was the Big Black samples stretched and savaged and smote completely; the sounds of birds, trucks, protests, and helicopters; or the low, insinuating tones encrusted with digital manipulation, the corruption, the destruktion, was total. There were no little ditties or ambient soundscapes, just obliviated airs and anti-environments. While, of course, no thing can be about nothing, it was difficult to escape a sense of vacuum here, an inert core around which Lescalleet had constructed his capital — gleaming spires of nullity and broad boulevards of implosion. It was equally difficult to visit that place without at least carrying back the faintest whiff of annihilation.

53

Lorde

Melodrama

[Republic/Lava; 2017]

What is this tape? The tape was Lorde’s album-long ode to the passion of youth and the beauty of destruction. It was a generational statement. Maybe I was a generation behind, but none of that mattered. I fell in love with this tape — its dazzling synth lines, introspective hooks, and Instagram-ready lyrics. No other pop record from this decade better captured living fast and dying young. Whether it was blowing her brains out on the radio or ending up painted on the road, Lorde (like so many singer-songwriters before her) distilled her experiences into universally relatable moments. This was what it felt like to be a 19-year-old in the 2010s. It felt like staying up late, alone in the dark, writing something. It felt like being the only person on a subway car full of strangers. It felt like something slipped under your tongue, the excitement of telling a friend that that one person texted you back. It felt like you were on fire. And this tape was worth sharing with someone you love so that your fires could feed on one another, burning brighter and fiercer. So what is this tape? This is my favorite tape.

52

Kendrick Lamar

good kid m.A.A.d city

[Top Dawg; 2012]

Are there any words that have yet to be spilled about the major label debut from one of the most popular rappers working today? Perhaps it’s worth honing in on the fact that good kid was personal and emotional, serving as an entry into a mainstay genre that isn’t frequently known for either of those things. Kendrick wasn’t immune to the characteristic bravado, but while that personality trait permeates among rappers seemingly out of career or cultural necessity, what we had on the album was a retrospective on youthful misguidedness. The machismo reflected on “Backseat Freestyle” isn’t who Kendrick is today, and similarly, the robbery described on the subsequent track, “The Art of Peer Pressure,” isn’t used as a feather in the cap by present-day K-Dot. It was clear as things progressed, and certainly by the end of the album, that the Compton native was more concerned with describing the mindset, commonly errant and adjacent to tragedy, that he had growing up in the 1990s and the 2000s. Clever flow and consistent production helped deliver self-awareness to listeners. Even most TV shows don’t have this level of character development.

51

Shabazz Palaces

Black Up

[Sub Pop; 2011]

It’s difficult for me to address Shabazz Palaces historically, because they initially struck me as an aberration. Overshadowed by a residual “O.G.” politics, their earliest EPs felt just a little too stiff, too needlessly esoteric, for me to fully enjoy, like a pre-Wu Genius close-reading Farrakhan. And aside from pulling the obvious “hipster rap”/backpacker card, calling these guys “old school” was probably the biggest diss you could lob; Ishmael Butler clearly wanted to do something different with his resume. So, hardly rejecting their posture’s awkward inconsistencies, Shabazz Palaces’ 2011 debut album Black Up pretended a subtle homage to the debased currency of youth. And it worked, all because it hinged on risk and diversion. I say risk because who, exactly, was clamoring for this kind of album in 2011? Who, exactly, was Shabazz Palaces for, aside from maybe Butler himself? Despite their continued presence and with the benefit of hindsight, I’m still not sure I know the answers to those questions, and I don’t want to pretend I do. Ultimately, it’s easier to define this album by what it wasn’t, rather than what it was — and it certainly wasn’t Take Care.

50

Julia Holter

Loud City Song

[Domino; 2013]

One of this decade’s great gifts has been the ability to hear the subtle transitions, and stunning transformations, of Julia Holter’s art. From there to here, her work stands as a discrete series of high points. Truthfully, any one of her albums, from Tragedy to Aviary, could be on this list, and no one here would question it. And still, here we are, choosing to recognize it from among the bunch. Why? I think, to begin with the lazy music-critical answer, Loud City Song was the first album of Holter’s that could qualify, if only peripherally, as pop music. People like pop music, and people like conventional narrative development in artists. (Some people even like cities and their loud songs, as well as their apparent signifiers — and how they all work back into pop music, and developmental narratives! Phew.) But listening closer, you’ll find that there is little Loud or City or Song in this album at all. Rather, the album works on its listener through an almost subliminal inversion: the loud is heard only in relation to a deeper, more pervasive quietude; the city is absorbed entirely in private rooms, in private sentences and in their words; and the songs themselves are assumed because the tightly composed drift in which they blow about suggests their shape. It is a marvelous thing to listen to that reveal itself like a secret, anew, nearly every time you listen. That this album can still play its beautiful tricks on us more than justifies its place, here.

49

Various Artists

Sounds of Sisso

[Nyege Nyege Tapes; 2017]

Much of the most innovative music around today emerges from hermetic scenes on the margins of the Global North centers of cultural production, & nobody can convince me otherwise. By definition, these artists are not recycling or mimicking imported tropes so much as rearticulating motifs from their own milieus in ways that elude the pigeonholing nomenclature in which “the outside” operates. What kind of music is singeli? It’s singeli — duh! Trying to communicate the aesthetic in writing (“it’s… uhh… East African gabber”) is precluded by the same futility that makes translations of foreign poems just glorified synopses; “you wouldn’t get it, so here’s the gist.” Fortunately, you don’t have to learn a foreign language to “get” singeli — just give up on that habit of expressing the marginal in terms of the hegemonic: gabber might just be European singeli. Indeed, the Dar Es Salaam scene is so insistent on commanding its own identity & future — not ignorant, but impervious & indifferent to the outside — that its spirit even seems inflected by post-colonialism. Writing from the Global South myself, I’m a sucker for that shit, keeping it on speed-dial ever since the Sounds of Sisso scene manifesto broke ground. While it’s heartening just how much love the singeli crowd has gotten in the past couple of years, we’re the ones who should be thankful; it’s an honor to have them on this list.

48

Arca

Mutant

[Mute; 2015]

Arca’s Mutant soundtracked my walks home from work in the late fall of 2015, my clothes drenched in the smell of a restaurant kitchen as I sauntered down dark sidewalks with aching feet. And for months, plugging in my headphones for the walk home, I would shrug, think “Mutant again,” and bathe in the fleeting euphoria of having finally clocked out. At that time, my life was mostly a lonely rhythm, and a monotonous, directionless one at that: waking up, going to class, going to work, walking home. Had I been more interested in what I was doing, it might have felt melodic, but it was more of a static buzz than anything orchestral. Then, quite refreshingly, Mutant came into my life offering barely any discernible pattern. Even its most serene melodies were cradled within the unpredictable and occasionally the grotesque. Ambience fluttered beneath cinematic non-sounds, unrecognizable flourishes of tonality and inflection. It was less an escape than reassurance that not everything is trapped within form and predictability, and that alternative narratives and histories can emerge quite unexpectedly and at the perfect time. Despite Arca’s fondness of unnerving sonic intensity, Mutant never wholly embraced destruction. Its core edifice seemed more concerned with occupying the space between ugly and pretty, between serenity and violence, a blur of ambiguity smeared onto the walls of whatever dared tried to contain or define it. As such, I found Mutant engrossing, almost literary for its cavernous exploration of feeling and depth, a poetics of the inexplicable. Mutant was never a way out, but a way in, a path toward something I couldn’t quite understand, and never wanted to.

47

Playboi Carti

Playboi Carti

[Interscope; 2017]

Drowned in pastels, an amniotic sluice of pillowy synths and subtly intricate drum programming, the production on Playboi Carti not only foresaw the coming decade’s hip-hop new age, but showcased exactly why Carti’s style would play an instrumental role in it. There was a numinous quality to Carti’s raps. It had something to do with the way his verses danced like light playing off a water’s surface. It had something to do with the intrinsic, lambent joy that the Atlantan rapper imparted — the way he could condense the very peak of a vibe or hype moment, stretch it, and then bottle it in song. The result being that, at any point in any given song, Playboi Carti seemed like the most alive person on the planet. Which wouldn’t mean a lot if the feeling weren’t so ridiculously infectious. But, above all else, it definitely had something to do with his deconstructed flow, a delivery that was no doubt one of the decade’s most aesthetically sublime musical objects, which the world came to know in earnest here, his first full-length effort. With a dazzling emphasis on vocal melody and mood, Carti rendered each track little more than a blank canvas for volatile ad lib improvisations. And the mixtape’s very best moments were, essentially, just that: one giant series of ad libs rushing in and out of the mix. The beats here, especially those courtesy Pi’erre Bourne, were precisely arranged to highlight the strange mechanics of Carti’s flow. If Young Thug is really the first “post-text rapper,” then Carti might be the first to transcend bars almost completely.

46

Farrah Abraham

My Teenage Dream Ended

[MTV Press; 2012]

Sometime around late 2014, I banned myself from listening to My Teenage Dream Ended. Something as simple as the filtered breakbeat on “Only Me,” the heartbeat on “Searching for Closure,” and the fade out to Hawaiian lap steel on “The Sunshine State” could easily trigger a devastating, irredeemable breakdown — the kind that leaves you twisted and inconsolable. After the cry hangover, I’d listen again. This happened for two years straight. The semi-rhythmic cadence and chilling treatment of Farrah’s voice became the narrator of these episodes, a stand-in for a permanent nervous breakdown echoing maniacally across the decade. Farrah’s accessible YouTube tutorial presence and reality TV persona would melt away into a Trecartin-esque figure, unhinged into abstraction. Producer Fredrick M. Cuevas’s heinous use of Vengeance™ sample packs — compressed into gnarled, blunt forms — supported Farrah’s haunted messages: the whispers of “don’t tell” on “After Prom,” her proclamations of “FLA Appeal to me!” over a single monophonic synth blast. For the love of American dubstep, for the love of perpetual auto-tune, for the love of all that’s evil in the world, we stanned into oblivion. In that oblivion, to quote Rowan Savage’s review, “the author’s Self itself is irrelevant, because it now encompasses the world, magnified — and in that magnification, reveals the seams.”

45

Earl Sweatshirt

Some Rap Songs

[Tan Cressida; 2018]

For an auteur, Earl Sweatshirt seems preoccupied with the understatement. Roughly the length of a Seinfeld episode, the L.A.-based emcee’s most personal work to date seeked to obfuscate itself. Its title was almost impudently self-effacing and the accidental cover art was likely culled from Earl’s camera roll or a Snapchat memories folder. He’s always been known for his reticence — his last record was called I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside, after all — but this effort established Earl as a hip-hop analogue to Richard D. James or Burial. Unlike Kanye, who has churned out his own his own string of comparably short releases in recent years, Earl didn’t require frantic rollouts or release parties to contextualize his work. Instead, he was an anti-persona of sorts, revealing himself solely through his verses, save for the occasional winkingly cryptic tweet.

If it were as accessible a medium as streamable album, Some Rap Songs could have conceivably found life as a poetry chapbook, its hacked-up jazz samples swapped out for a Xeroxed photo-collage or some vague film photography. Most tracks clocked in at around a minute and a half, carried by a conversational open-mic-night delivery and unvarnished instrumental loops that growled and undulated like stirring creatures. The production was swampy — beyond lo-fi, even — and it was Earl’s pen that prevented us from drowning in the murk, intentionally sending listeners to the internet to find transcribed lyrics.

On wax, Earl’s writing sounded effortless and casual. On paper, it divulged its poetic complexities. Compressed into dense chunks of meaning, stanzas bulged with subtext and tucked emotional weight into enjambment. Earl gave updates on his life like a human projector reel, eschewing lyrical scene-setting for disjointed slideshows of snapshots: picking out his father’s grave, finding new collaborators in MIKE and Medhane, bad trips. Images passed by as unpredictably (and sometimes as painfully) as calendar dates being retroactively filled in.

“Why’s it so muddy in the creek, poet?”

Earl’s at his best when he just misses the mark, carving out ghostly tableaux with the bluntest edge possible. “Imprecise words,” indeed.

44

D’Angelo

Black Messiah

[RCA; 2014]

“Who will survive in America?” How do we conceive sexual healing when bodies that bend into kisses are subject to hails of police-sanctioned bullets? How do we sing soul when we can’t breathe? Two truths: soul music, the righteous reaffirmation of the revolution as incontrovertibly bodily, is incontrovertibly America. And: the premeditated extermination of brown bodies is also (incontrovertibly) America. This is the world D’Angelo returned to; this is the world D’Angelo left. Over the squelches and heaves of Black Messiah, confusion and outrage emerged, a gospel anger over real fear. Even that falsetto, the one we’ve always quivered for, cannot balm the truth we heard articulated every day of this agonized decade: this world is killing us. And yet alongside that anxiety was a love and a joy so hot and bright we felt opened up and sated in an embrace we’d craved, still crave. Hate and love on two hands. This too, is not a contradiction. The stakes of those poles, the duality and want in D’Angelo’s voice, we heard the struggle of every body seeking the right to be alright. Black Messiah, the fire this and next time, burned like Langston: “O, yes, I say it plain/ America never was America to me/ And yet I swear this oath — America will be!”

43

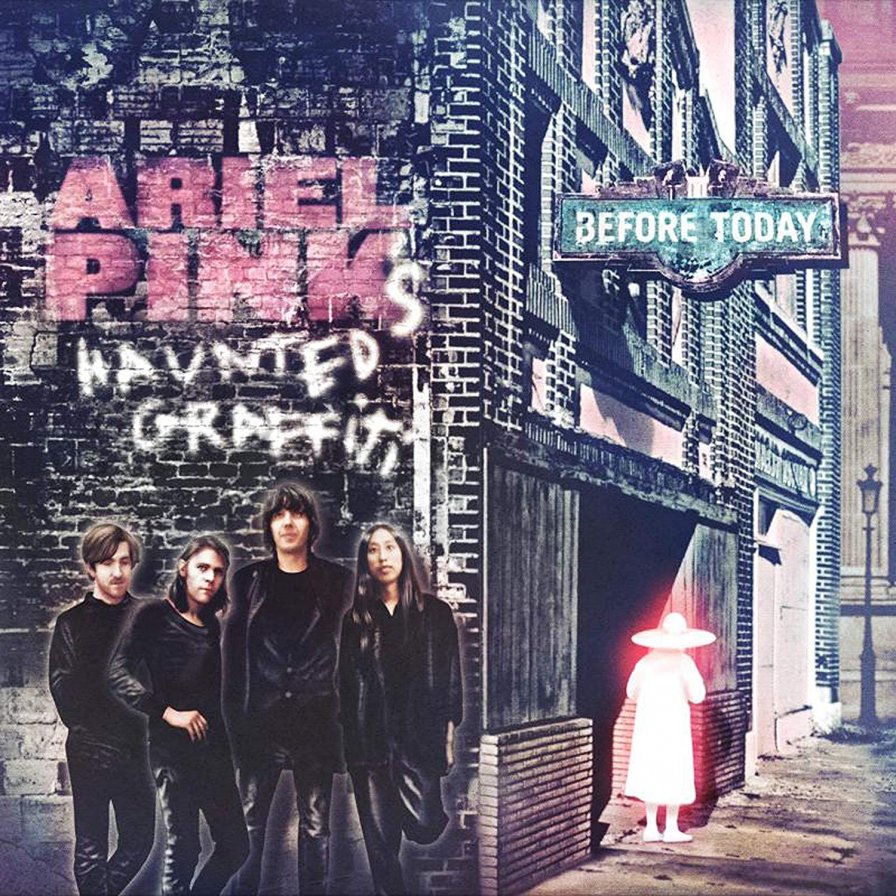

Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti

Before Today

[4AD; 2010]

Ariel Pink spent most of the 2000s establishing himself as the new golden child of lo-fi music, recording wounded, nightmarish pop songs that carried the same torch as outsider geniuses like Tonetta and Daniel Johnston. At the height of the late-2000s indie boom, however, he leapt to the big leagues by signing with 4AD, taking his act to a new level on par with heavy hitters like Animal Collective, Deerhunter, and other groups who seemed to be proving that notions like “bands” and “albums” were still doing just fine. Then in came Pink with Before Today, a murky, dissociative haze of a pop record that slinked through a nocturnal wasteland of butt-house blondes and menopause men, all held together by yacht-rock hooks and the yelps of a man who sounded as desperate for sex as he was for fame. But there was truth in Pink’s sardonic pleas; unlike his peers, Pink saw the era of rock & roll disappearing into the rearview, dissolving like mush alongside all the tacky pop and TV jingles that we had previously ignored for so long. Before Today honored these forgotten cultural artifacts, elevating them to impressionistic heights with unbearably beautiful songs that cut through all of Pink’s raunchy pranks to capture the dying wish of a washed-up generation of wannabes. It was pop music built from the memories of a time now out of reach, a sound fading further and further into the distance, becoming more distorted and dreamy with each passing streetlight.

42

Fiona Apple

The Idler Wheel Is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Cords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do

[Epic; 2012]

For the first three albums of Fiona Apple’s career, Jon Brion was a major factor. He played a slew of instruments on her groundbreaking 1996 debut Tidal, repeated the feat while fully producing 1999’s When the Pawn…, and had produced the original version of 2005’s Extraordinary Machine before Apple decided to re-record most of it instead with Mike Elizondo and Brian Kehew, though the results didn’t end up venturing far from Brion’s Mellotron-esque cinematic big band wheelhouse.Taking a full seven years to concoct her fourth album, 2012’s The Idler Wheel… saw Apple explore a rather minimalist aesthetic. Her lyrics were as fierce, emotional, and poetic as ever, but the sound was dramatically stripped down. Produced with touring drummer Charley Drayton, he and Apple (credited as Seedy and Feedy) played a myriad of eclectic instruments, from autoharp and celesta to bouzouki, kora, and Teisco, yet it always felt like simply hearing two talented musicians jamming in a room. Although the sound still delivered her typical orchestral lushness, the sparse rawness gave space for Apple’s vocals to connect on a visceral, primal level. It hit you right in the feels.

41

The Caretaker

Everywhere at the end of time

[History Always Favours The Winners; 2016-2019]

Borne of fascination with the haunted hotel ballroom of The Shining, Leyland Kirby’s The Caretaker project had long used manipulated and repeated phrases of early recordings to probe concepts of memory and mortality, but Everywhere at the end of time was a more systematic attempt to auralize the process of decay, disruption, and disintegration associated with a particular neurocognitive disorder, encapsulated in the premise that his Jack Torrance-channeling alter ego was stricken with dementia. Beginning in 2016 and released as 6 albums over the course of the following 3 years, these installments began with slightly altered — slowed down, reverb drenched, but fairly wistful and mellifluous — fragments of lighter-than-air ballroom pop, drifting in and out with a feeling of reverie. Smatterings of record-surface noise accented these songs in ways connoting nostalgia. By the end of the series, though, the signal-to-noise ratio completely tipped, with anything resembling more natural instrumental timbres mostly buried under layers of rumbling and crackling bass that were disorienting and ominous. This was the sonic simulation of the self dissipating into oblivion. The total experience was the deep subjective horror of losing oneself, an encounter with the abject, and the result was one of the most ambitious conceptual sound works of the 2010s.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series