We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

“I can hear everything. It’s everything time.”

Here we are, floundering at the tail end of the decade, grasping to make sense of the last 10 years, when that ancient quote (actually from Gang Gang Dance in 2011) had already provided this decade’s temporal framework for what feeling and existing might look like this decade. This quote, this foundational assumption, presaged this decade’s perceptual and material eruptions of sounds, of images, of ideas, of bodies; reducing our grandiose theories into beautiful yet fairytale simulations of purity and vanity — into rain and glitter. It was a statement, but also a warning, heralding — perhaps even willing into existence — what was to come: a decade both explosive and incomprehensible. It was everything time, and we could barely handle it.

Time, this decade, figured as much into our writing as words themselves — even when we didn’t realize it — and the same could be said of its music. Many of our early favorites this decade, from James Ferraro to Ariel Pink to Oneohtrix Point Never, would effectively swap traditional notions of musicality and engage directly with phenomena like nostalgia, cultural memory, and the corresponding junk left behind. No longer just a simple, comprehensible repository for things that happened, the past became part of the exclusive present, because distinguishing between the two increasingly felt like what time eventually does to the differences between 3rd and 4th grade, or what increased distance does to rocks and pebbles. Our past was not just aestheticized for apolitical nostalgia, ironic indulgence, or mindless repetition; the past was restaged, reperceptualized as a disruption in our listening, calling into question our entrenched, vestigial expectations concerning “originality” and taste. The results were sensually provocative and perverse, sometimes even confoundingly rote, but it infected the entire decade, offering dynamic, multilayered ways to not only subvert our temporal orientation, but also explore how affect itself could challenge our assumptions about resistance under capitalism.

And indeed, most of our favorites this decade didn’t hinge on signaling their politics. (Didn’t need them to either. We have plenty of ways to know when we’re getting fucked.) From vaporwave’s radical appropriations and Kanye’s destructive provocations to PC Music’s wild HD pop experimentation and Dean Blunt’s drifting, ephemeral gestures, this decade’s most controversial musics — at least the ones we cared most about here — were not marked by political upheaval or rupture, but by ambivalence and ambiguity, even uncertainty. This decade, it was OK to not know whether you “liked” something or understood what was “meant.” It was OK to not be able to envision a future because our depictions were always-already anachronistically displaced. It was OK to not force yourself to choose between celebration or rejection, because our art’s value was in perpetual oscillation. Music, here, was quickly dematerialized, reterritorialized, and re-coded for algorithmic consumption (18+), collapsing and folding into itself (E+E), stumbling into bizarre juxtapositions (DJ Rashad), calling attention to the medium itself (D/P/I), and vomiting brilliant recombinations (Klein). This restaging of aesthetics happened almost instantaneously (Lil B), sometimes accidentally (Farrah Abraham), and oftentimes originating from and rapidly reproduced by quick-witted, meme-savvy teens who had no reason or incentive to explain themselves.

So, yes, sometimes it was about having faith in the creative output. But other times, it was about having faith in selves. In this decade, it was okay to cry, to embrace our E•MO•TIONS, to vamp on our mercuriality. In this decade, death was real. Representational and symbolic exchange is always subservient to material transformations, and some of our favorites offered quite devastating ways to mourn, from Carrie & Lowell to A Crow Looked At Me. Still others deepened how we relate to our bodies, uncovering new materialities and new compositions (Elysia Crampton), exploding our “normative biopolitical imperatives” (SOPHIE) and “demanding transmutation” (Arca). We witnessed this shift in many of the artists on this list, and some of us underwent (and are currently undergoing) this shift ourselves. And yet we were constantly reminded that our bodies, while forever expressive, were also forever exploited. They were trapped in “corrupted relations that exist between postcodes” (Babyfather), hopelessly tethered to the “elaborate wretchedness of humankind” (Scott Walker). Who-we-are was in conflict with what-we-do, and the ambient technologies that enabled much of our communication this decade provided exactly the kinds of platforms that would encourage not civic participation, but data generation. Before we knew it, “taking a chance” meant adding a new brand of deodorant to our shopping cart. Welcome to the future?

If the correlate of a past that’s endlessly reproduced is a future that never manifests, perhaps imagined futures simply lost their critical role and had become junk themselves. Perhaps they were simply cultural artifacts rendered meaningless through a technological materialism that offered both sensory replenishment and heightened temporal awareness. The future, just as with the past, was not immune to the aestheticization process, as shown in our decade’s obsession with futurity. But sometimes all it is is scope — rocks and pebbles. Because if we zoom out — from the days to the months to the years, to the decade and beyond — what we find in the chase for that elusive wholeness, that unifying element, is that the thing that gets you to the thing has always been another thing. Music, for us, was one of those things. We often framed it with theory, but we felt it as desire, and it dripped from our ears, like nectar. A sweet, sticky, golden everything. While music articulated the complexity of our feelings this decade, changing us from the inside until our insides were inside-out, it also reminded us of a simple yet paralyzing tragedy of personhood: the moment we’re always waiting for is likely a replica of one we’ve already felt — and may never feel again.

This is what time does. It eventually renders even our most obsessive desires moot, as we move from crisis (financial) to crisis (ecological) to crisis (individual). Everything is fleeting. But unlike the first decade of TMT’s existence, in which it was often marked by privileged discernment, “intellectual” curation, and faith in the noisy subversion of capital (look how that turned out), this decade we strove for disunity, telepresence, and multiple perspectives: how our lack of consensus made room for possibility; how we embraced trends and transition in a time of sensory abundance; how fluid identities could emerge through syncretism, hybridization, and bottom-up subacculturation; how we practiced embodiment to tell cute stories about affect, movement, and sensation; how nuance offered passageways to our own materiality; how our music provided counternarratives and problematized notions of truth; how noise was no longer our noise (but was actually our noise all along); how we found in our music semblances of healing and palliative care in response to some exhausting, though not unprecedented, years.

We all know how those later years felt at home, under the covers, anxiety draining our souls, but those very same years felt different while clicking around on the web. Time plays differently here. In virtual worlds like Second Life, time has no immediate aesthetic effect: nothing crumbles, nothing washes away with time. Even if all of the avatars staged a mass exodus, it remains preserved forever in its eerily pristine, uncanny state until intervention, whether it’s a code update, through technological obsolescence, or actual physical disconnection of its servers. In our world, here at Tiny Mix Tapes, time shows itself in our digital ruins, manifesting as technological breakdown and incompatibility: broken images and incorrectly rendered text, conflicting coding languages and unreadable characters, dilapidated streaming embeds and exhausted hyperlinks pointing to a musician who may or may not have ever existed. It’s long since happened to early versions of the site, going back to our Geocities days in 2001, and we can already witness this process happening even in the posts we published this decade. The digital deterioration is real, and it’s both haunting and beautiful: the former because our identities become threatened by a past that eats away at itself, and the latter because the deterioration will eventually create space (physical, emotional, virtual) for something new and different.

This is something to celebrate. This is what we want (even if it’s fake). TMT wasn’t made to be projected into the future, nor was it made to be a forever lasting anything anywhere. That’s what plastic’s for, and there is beauty in letting go. Who knows what the next decade will bring, but as this one comes to its anticlimactic close, bringing us no closer to truly understanding our world but perhaps closer to accepting and embracing our eventual deterioration, the truth is, we don’t even have to think about music anymore. Words are just words that you soon forget (Laurel Halo), and while we all do stuff, sometimes stuff does itself (PC Music). If our most prolific artists (Lil B, Dean Blunt) taught us anything about excess in a supposed age of specialized, niche-driven taste — a marketer’s paradise, by the way — it was that we’re all really just amateurs, winging it. We love theory and criticism, but they alone won’t save us from anything. All we can say with confidence is that, past the cultural explosion and incoherency of this decade, through the blurriness of everything-time and its spectral hold on how we perceive the world, we here at TMT feel overwhelming gratitude: for the time we spent together as a scrappy yet passionate family of “writers,” and for the time we spent sharing with you, “the readers.”

Sincere thanks to all of you out there. We are eternally grateful that anyone anywhere was willing to join us in this experiment in criticism and music writing. <3

To close out the year, we are sharing our Favorite 100 Music Releases of the Decade. It was compiled from individual lists by current writers and some former, with minimal intervention. To prevent every single Dean Blunt release from occupying a spot on the list, we imposed a limit of two releases per moniker. So, yes, this means that many favorites are missing (find some of those here, here, and here). We apologize for any inconvenience this may have caused.

100

John Maus

We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves

[Ribbon/Upset The Rhythm; 2011]

Find a free text-to-speech. Copy this blurb into it, pick the homie “Charles” (he has the best voice), and press play. Now, close your eyes and listen. Envision a Lazy River that would top a Travel Channel “best of.” Now immerse yourself in it. The water temperature sits in that sweet spot between “little more than lukewarm” and “first step into the shower” — the Maus Zone. Can you feel it? Let the river flow through you in its unique, tantalizing ways — it has an innate fluidity that could both kickstart a party with friends and cause you to cry driving alone on the Florida Turnpike. Now imagine nearby innertubes playing analogue synth and spoken word tapes of Alain Badiou until slightly deflated, and then listen for a piercing guitar lick here and a synth wail there. This is the music of the Maus Zone, and at the turn of the millennium, this completely ecstatic, life-affirming sound expressed itself as We Must Become the Pitiless Censors of Ourselves. It was, and still is, worth every moment.

99

Kara-Lis Coverdale

Grafts

[Boomkat Editions; 2017]

In recorded music, there is always an end. We’re keenly aware of it, and that expectation of a conclusion, of a piece ending, is integral to how we experience music. But on Grafts, Kara Lis-Coverdale used some type of magic that we couldn’t quite explain. Every time we listened, it was as if we had entered a timeless vacuum. There was nothing around, except a moving, glittering display of heavenly lights splayed all around, lapsing over each other like waves. It was like the packaging was gone. Rather than feeling anxiety over its impending end, we felt in control, as if we could stay in “2c,” “Flutter,” and “Moments In Love” forever. But, despite the poignancy of Coverdale’s spell, the music didn’t go on forever. We could always go back and stare at the lights as long as we were around — and we often did — but there was indeed an end. There is always an end.

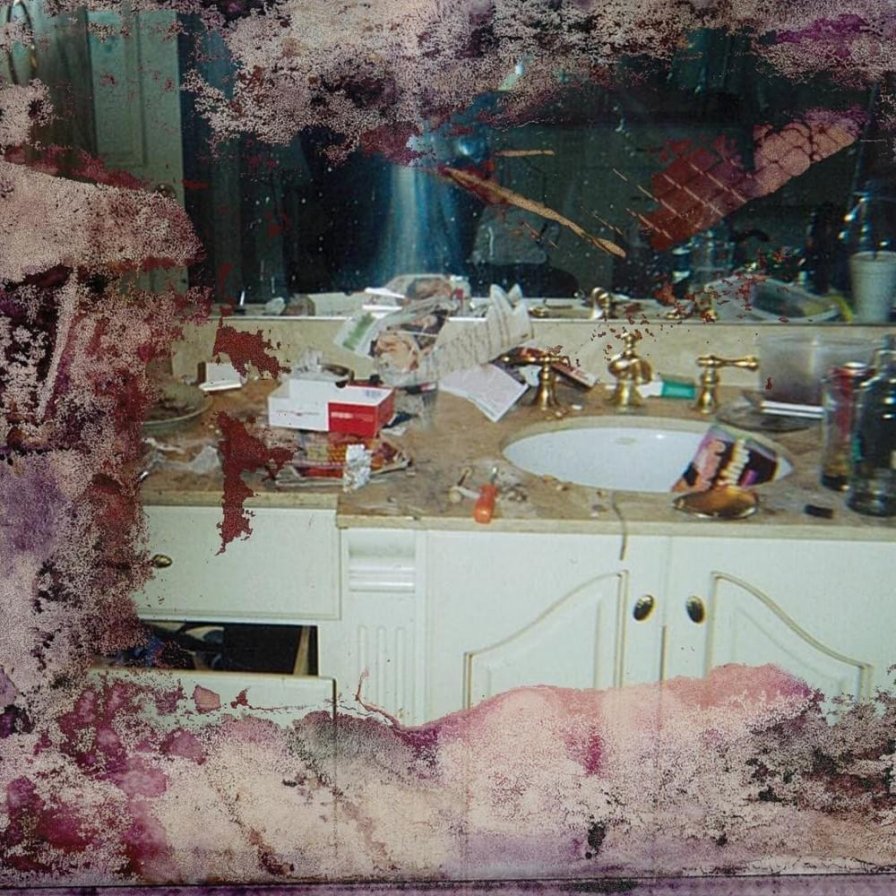

98

Pusha T

DAYTONA

[G.O.O.D. Music/Def Jam; 2018]

Pusha T’s DAYTONA served a perfect course and deserved a star from the tire people. What was not to like? Pusha’s calligraphic, unmistakable flow; a chef with a savory cut in rare supply. Kanye’s taste in suppliers, his attention to detail on every beat. The love for the material, the proportions; it all mattered. Every bite worth taking. Each piece a scrap of soul worth more than its weight in gold. A life told in layers — the tarnish, the beauty, the new material between. Hold still and sense his history. Organic poetry. Hot sauce and tennis balls. Life baked in. Ye rang out. Reduced, condensed. Perfect timing, perfect amount of heat. Stopping just short of too spicy. Haute suite. Look, there’s obviously still gonna be some things that only T gets to know. But it went deeper than that. You can’t teach it, you know? DAYTONA, this little thing. Can I have some more?

97

Deerhunter

Halcyon Digest

[4AD; 2010]

Here we are, nearly a decade down the road from the release of Halcyon Digest, and the album has littered my personal memory databank with traces of its 11 marvelous tracks. Miming along to the saxophone parts on “Coronado” while standing on the lawn of my decrepit college house. Soaking in the isolated stillness of “Sailing” to accompany feeling like my heart had been punted across New England. Closing my eyes in Webster Hall and being lifted to the sky as “Helicopter” folded over itself and exploded in inevitable breathtaking fashion. Honestly, it feels quite fitting, as Halcyon Digest was itself an album of memories, hazy recollections of past lives both real and imaginary. It was pictures and words and designs, cut out of old magazines and rearranged into something new. Cover versions of Golden Oldies that never existed. It was hearing “Desire Lines” for the 60th-odd time and wondering yet again if one day it would be physically possible for humans to live inside of a song. Something fleeting and ephemeral etching itself into permanence.

96

Bill Orcutt

A History of Every One

[Editions Mego; 2013]

Guitarists will sometimes warm up by hitting their strings a little before starting to play. For composer and interpreter extraordinaire Bill Orcutt, sometimes hitting is playing. Indeed, there were sequences on A History of Every One that were downright barbaric on first listen. As soon as Orcutt’s treatment of the trade union morale-booster “Solidarity Forever” started, it was obvious that we were in for a one-of-a-kind slab of magic. But with traditional spirituals standing next to festive fretworkouts and minstrel and work songs marching alongside two Oscar-winning Disney ditties, there was a different sort of fairytale glitter going on here. A History of Every One was still a lovely piece of lunacy, however, and despite many moments of extreme strain and disorder, the album had a sweeping, strange beauty that has been making our heads swim since its release in 2013. Far from being a time capsule, the album pointed a way forward in free expression, and everything worked. Containing a dozen tours de force, each one indistinguishable from its most common — or most deformed — version, A History of Every One was a let-it-bleed collision of energies that is still one of the more “alive” guitar experiments you’ll likely ever hear.

95

Beyoncé

Lemonade

[Parkwood/Columbia; 2016]

Where Beyoncé established Beyoncé as a brand, Lemonade positioned said brand as a mode of performance art. Knowles-Carter had already turned her releases into unannounced audio-visual events with her self-titled 2013 album, but with Lemonade, the pop icon’s not-so-private personal life and changing relationship to American and global media consumption seemed inextricable from the project’s genesis, distribution, and reception. Released exclusively on the artist’s own streaming service, accompanied by a 65-minute film on HBO, the album’s tracks played like 2016’s feminist response to Here, My Dear, preceding the #MeToo movement just as Beyoncé’s Super Bowl performance of “Formation” (the album’s lead single turned bonus cut) preceded the NFL’s identity crisis, the latest terms of which are now being negotiated by none other than Beyoncé’s husband. Considered alongside 2017’s 4:44 and 2018’s Everything Is Love, the album also kicked off a trilogy of brilliantly transcendent, if also tellingly misunderstood, sociopolitical treatises from the Knowles-Carter family. Perhaps most importantly, though, Lemonade was the decade’s most ambitious break-up-to-make-up album, one for life partners to argue over and embrace together like no other. Who knows? If C Monster saw it premiere with Savannah, maybe it’d be his favorite Beyoncé album, too.

94

Zs

New Slaves

[The Social Registry; 2010]

New Slaves hit me hard in the chest and never left. Every song was a law, a sculpture of raw energy, a spectacular commodity. Twisted and beautiful, wrought from astounding performances and inspired studio magic, New Slaves is still revelatory 10 years on. It was in 2010, at my (and Jonathan Dean’s) beloved campus station, when I first heard “Gentleman Amateur,” which instantly hooked me on the group. And it was also in 2010 when Tiny Mix Tapes ruptured itself and gave New Slaves the #1 slot in its year-end rankings, which is also the moment I realized that this site knew what the fuck was up and I needed to write here. But 10 years on, I still can’t adequately explain how amazing this record is. I can barely even explain how it sounds. “Unique chamber music compositions using rock instruments, microtonalities, and extreme textures that never underestimate their audience or compromise on execution.” “Noisy, raw, gorgeous, difficult, caustic, cleansing, numbing; a slowly exploding beautiful art bomb.” Something along those lines, but better. I would want to assign a specific turn of phrase to it, to coin something unique to describe this stunning record’s idiosyncratic noise vision. But the best music is always hard to explain. That’s what makes it so: the impossible things it conveys that can’t be captured in language. The things it fantasizes aloud, the new fantasies it creates in turn. There’s proof of something here, something we haven’t figured out yet, buried deep in the chaos. Some new model for living, adapting, and surviving. With it comes this strange optimism, that the harsh rigors of the reality you find yourself in can be worn, like armor — the proud decorum of a future corpse.

93

Bill Callahan

Apocalypse

[Drag City; 2011]

I share a space with Bill Callahan. It’s not a small space, it’s a city. We see the same sights over and over again — violet-drenched sunsets, eternal grids of highway chrome, the crystalline owl peering above the Austin skyline. The same grocery stores and gas stations and the DMV. Existing day-to-day in a space like this, the wondrous and the mundane begin melting together, smearing like the mountain landscape of Apocalypse’s cover. Bill Callahan’s masterpiece resides within that smear, coming across as both grounded and unknowable. Our home country, which contains our home city, which contains our home structures (physical, social, interpersonal), is viewed bleary-eyed from Australia, its avatars a legendary talk show host, four legendary country singers, and a small sampling of our atrocities, not legendary but sickeningly real. By the record’s end, Callahan has denounced the life that so consumed him a half hour of album-time prior, settling into a gentle ride and ultimately becoming the road itself. Has he finally become something so ethereal and beyond himself that he exists only as part of the landscape itself? Absolutely not. His final words on Apocalypse: “DC 450.” It’s the album’s catalog number, reminding you that this is an album, a finite work of art that, brilliant as it may be, simply exists.

92

Actress

R.I.P

[Honest Jon’s; 2012]

In a time when time ran backwards (2012, to be precise), rising soccer star turned archeologist Darren Cunningham excavated fragments of recordings from a time after human extinction. Caked with lime, richly warped and discolored by mold and decay, haunted by chrominance signal ghosting effects as well as actual ghosts, these artifacts had nonetheless survived, on the whole, in an acceptable state of preservation. It was determined they were/will be created by AI military think tanks in a style that exhibited vestiges of 21st-century rap and house and suggested a corollary interest in the by-then obsolete concept of “Dance.” The think tanks were/will be specifically mandated to reverse-engineer and weaponize the concept of “emotion,” and their inability to grasp anything but its surface manifestations, combined with the organic processes of reverse time and reverse soil and a software-driven sense of intellectual longing, created its own unique textural poignancy that found its way into unexplored human neuro-pathways, arousing actual emotion amongst the final generations (in forward time) of homo sapiens to survive on planet Earth.

91

David Bowie

Blackstar

[Columbia; 2016]

Blackstar was recorded in secret and released two days before David Bowie died from liver cancer. Bowie knew this was going to happen, but we didn’t. I’m interested in those two days. Now, we can’t separate these events from one another, Blackstar and David Bowie’s death, but there were 48 hours where the album was just another new project from an aging rocker. As we look back on Blackstar, there’s a strange way in which Bowie lives beyond his death more than some others who die, because he’s rooted so deeply in this object. He affects us from it, and so he doesn’t seem truly gone. A highlight of the 2010s and one of Bowie’s most powerful records, this album continues to remind us that the things that unfold in this world change the way we see artworks. The dark grooves of the prescient “Lazarus,” the devastating new meaning of “I Can’t Give Everything Away,” the frenetic cadence and the mysterious sci-fi frame of the title track. What were those two days like for people who were listening, before this album became what it is now?

90

Jenny Hval

Blood Bitch

[Sacred Bones; 2016]

Jenny Hval spent the first half of the decade putting words under a microscope with lyrics that were at once blunt and razor sharp, where music (or sometimes just sound) grew organically from her confident yet deadpan delivery. While Blood Bitch was a culmination of that process, it was also a turning point. Hval’s self-examination expanded to an exploration of identity stretching time, space, gender, and myth, delivered with a newfound sonic warmth (“Female Vampire”), vocal tenderness (“Period Piece”), and lyrical vulnerability (“Conceptual Romance”). But in a decade where heel-turns to pop music came to feel like a cynically predictable career strategy for experimental artists, few on either end of that spectrum took the kind of risks Hval threw herself into. The gasping, out-of-breath pulse running through “In The Red,” the screamed panic of “The Plague,” the whispered dream diary of “Untamed Region,” and even the candid question “What’s this album about Jenny!?” blurted out right in the middle revealed an artist able to make her music more challenging and spiritually probing than ever, all while embracing pop music on her terms. Blood Bitch was one of the most open-hearted albums of its era, even — or especially — when it was dripping with blood.

89

infinite body

carve out the face of my god

[Post Present Medium; 2010]

At the turn of the decade, harsh noise expat Kyle Parker sighed ambient tracks of relief more suitable for avoidance than integration, going away than getting along. As the self receded into absence, “Dive’s” slow fade in of granular chordal melds resonated with coarse serenity inside the curved bowl of an empty skull. Moving his carapace through symphonic mandala (“A Fool Persists”), trailing expoflora (“Drive Dreams Away”), and marine life (the title track), Los Angeles-based Parker looped and steered his exhausted orchestra-of-one in an aftermath of fraught nerves. Embedded in the collection of post-escapist sustainments, beacon track “Sunshine” blinked ChipCorder-esque throbs across an overcast outstretch of dull haze and polymeric shimmer. Spatial and substantial, linear and circular, Carve Out The Face Of My God die-cut hollowed-out residue from hallowed music into flatlines that reflected the nihilism in the divine, and vice versa.

88

The Knife

Shaking the Habitual

[Mute; 2013]

Before we get too deep into this, I feel this obvious detail deserves recognition: Shaking the Habitual, as a title, was dead-on. I mean, even beyond its cheeky referencing of Foucault. Sure, Karin Dreijer Andersson and Olof Dreijer were committed to “[shaking] up habitual ways of working and thinking… [of re-evaluating] rules and institutions,” all that good post-structuralist shit, but what really made it resonate like The Concern for Truth never could was how truly SHOOK it left us all. This thing was so fucking monsterous, it famously broke our scoring system. I once listened to it very loudly and in its entirety on a plane; somewhere around “Crake,” I thought there was a real possibility that we were going down (what with all that clanking), but I vividly remember being way too unconcerned about it. Shaking the Habitual’s genius was that it riled you up — about gender stereotypes or fracking or boring sex or whatever — but it never killed your mood. There was a dreadful irony here that music like this could, through its physicality alone, relinquish our grip on our privileges, our violent habits, our possessions, that these sick beats and synth squelches could “end succession” if only more people would hear it. The Knife were bent on “failing more” though, but not before they succeeded in completely dismantling everyone’s expectations. Maybe this is where it starts though: with a flurry of wooden clicks and breathy chirps and rapturous screeches, like cracks in a dam holding back hoarded wealth, like an unshakeable urge in the left foot of a billionaire who’s never danced. In all honesty though, thinking about kicking capitalist habits is hard, but when this shit is on, I’m ready to lose. Bring it on.

87

Amen Dunes

Through Donkey Jaw

[Sacred Bones; 2011]

For Damon McMahon, the transformation from Mark Tucker to T. Storm Hunter occurred sometime during recording “Jill.” The manic, fragmented psy-fi of its locus: a discombobulating melody that bounced across every surface, sounding like a stalled Bataszew. It was the beginning of a disconnect from D.I.A., but it was also the mutagen that further separated himself from an outsized beginning. McMahon once lamented that he hoped Through Donkey Jaw would be hated, because he thought it wasn’t quite as sincere as his future recording output would be. But here we stand, and Through Donkey Jaw might be McMahon’s most sincere output. The range of emotions were uncontrollable. McMahon ripped his old formula to shreds, disassembling it one song at a time until the record ended in a scrapheap of teary-eyed confessionals. The road McMahon has taken since has been lengthy, but each subsequent release has recalled Through Donkey Jaw’s imitable spirit in some way. And as he’s polished his ride to a fine sheen, he hasn’t buffed out the well-worn scratches or picked at the rust. McMahon has never been able to shake his confessional tune, never abandoning his own version of Tucker’s 1964 Cadillac. In fact, unlike his predecessor, he’s come to own it as the reliable, if beat up, mode of transport is was built to be.

86

Rich Gang

Tha Tour Pt. 1

[Cash Money; 2014]

Obviously, we don’t accept the term “mumble rap” as a meaningful genre descriptor: Listening to this towering mixtape collaboration between Atlanta innovators Young Thug and Rich Homie Quan does not entail any of the strain implied by perceiving spoken words beneath the friction of mumbling. It’s instead a pure thrill to revisit Young Thug’s exuberant leaps in pitch, his tangled, unpredictable flows, his syllables flung like Jackson Pollock drips. And though less influential, Rich Homie Quan is a gripping stylist, too, his drawl smeared, dipping in volume, marked by inventive dynamics and repetition. The mixtape was a lexicon of ear-worms. Every song was memorable, and yet our ears were able to pinpoint new phrases with each spin. We listened while availing ourselves of the crowdsourced transcriptions on Genius, comparing what we heard with the majority opinion. We listened by firing up old hard drives of leaked MP3s or prying open the browser window of DatPiff. (This mixtape is still not available on major streaming services.) Even though the term “mumble rap” still sucks, listening to Tha Tour Pt. 1 made us reconsider the term as a reminder of the way Young Thug and Rich Homie Quan helped us hear, in all audible language, the eruption of melody out of speech.

85

Helen

The Original Faces

[Kranky; 2015]

There’s a scene early in the 1989 film Weekend at Bernie’s in which star Andrew McCarthy attempts to extract his boom box from an impressive amount of tar built up on a steamy NYC rooftop. This imagery — a boom box encased in muck — is an apt metaphor for the sounds produced on Helen’s 2015 album, The Original Faces. Liz Harris (Grouper, Nivhek) was joined here by pals Jed Bindeman and Scott Simmons (with backing vocals by the mysterious “Helen”) for a 12-song missive of what might be referred to as “surf noise,” if classifying such things is important to you. Beginning with the pleasantly noodling “Ryder” and ending with the short-but-sweet title track, the group burned through 33 minutes’ worth of sonic downer bliss; even the songs lasting south of two minutes left an indelible mark. But despite its relative brevity, the music was catchy and dense enough that you’d find yourself discovering new sounds deep in the mix, like diving through a new cereal box for the prize buried at the bottom. The Original Faces was the type of album that socked you in the stomach for your lunch money then tripped on its way out the door, a roaring yet surprisingly tender addition to Harris’s distinctly overachieving and achingly gorgeous oeuvre.

84

D/P/I

Fresh Roses

[CHANCEIMAG.es; 2013]

Microseconds into the opening pitch-shifted warble of “In Dreams” — wait a minute, is that Roy Orbison? — I knew there was something special about Fresh Roses. Alex Gray’s D/P/I project always had a sort of capacity for serrated incision, an ability to recombine the sonic lost & found into a thrumming beat or a collage or an open-source cave painting that pointed 13 different directions at once. But there was something so crystalline about Fresh Roses’s vision. It sprawled from the towering centerpiece of “DEPRESSION SESSION,” a piece wherein we were cast about by the (de)motivation of a TED talk’s angry older brother while hard drives went senescent in the periphery. Country songs melted, beats were cheese-grated: WAKE THE BODY BACK UP! Forgive me, but in the last 10 years, so much that was SUPPOSED TO BE SOFT went hard as rock. What stage of post-irony are we in again? Who’s in charge here? I can’t remember cuz I deleted most of the note on my phone where I was keeping track. All it says now is “Fresh Roses.”

83

Andy Stott

Luxury Problems

[Modern Love; 2012]

Andy Stott has had his finger right on the pulse this entire decade, but Luxury Problems in particular continues to hit just as hard as it did in 2012. Shortly before its release, after years of balancing his techno output with a day job at Mercedes, Stott quit the luxury car business. The change deconstructed the rhythm of his life, day bleeding into night and back into day, as if time belonged to another existence. And that was the sound of Luxury Problems — techno that lost all sense of urgency, all sense of compulsion. Techno that techno’d to techno, for no one and nothing. And yet it was so alive, like the beating of some dark, dank heart powering the underworld and, indeed, the one above ground, too. Still, the most we could do was feel its heat; we knew it was there, but we couldn’t know it in itself, separated as it was by an impenetrable and unknowable mass. To get lost in non-time was the ultimate luxury problem, and the record took us right into it, enveloping us in a peculiarly woozy sludge that we willingly got ourselves stuck in. It was a beautiful, even inviting, sludge, thanks to Stott’s old piano teacher Alison Skidmore, whose layered, decaying choral vocals were otherworldly and perfect for Stott’s compositions. The collaboration was fruitful in a way that Stott could not have imagined when he reached out to her. I mean, they hadn’t seen each other in 15 years! Go ahead and call your old piano teacher. Try to make something as good as Luxury Problems.

82

EMA

Past Life Martyred Saints

[Souterrain Transmissions; 2011]

The first song on Past Life Martyred Saints ended with Erika M. Anderson declaring “Great grandmother lived on the prairie/ Nothin and nothin and nothin and nothin/ I got the same feelin inside of me/ Nothin’ and nothing and nothing and nothing.” Was it emptiness that Anderson felt? A lack of agency in a world where her role was sharply delimited by forces outside of her? Or did we detect something productive in this emptiness, something of the pioneer spirit of her ancestor that suggested limitless possibility? The ambiguity that characterized these lines permeated the record as a whole. The imperative “Momma’s in the bedroom, don’t you stop” from “Breakfast” could have been either the breathless command of a young lover or something infinitely darker. Her lament on “Marked” that “I wish that every time he touched me left a mark” could have signified either romantic yearning or a desire for evidence of the damage inflicted upon her. It was from this muddiness, this imprecision, that the album gained its potency. What broke our hearts was Anderson’s willing recognition that you don’t stop loving the things that try to kill you, even when you know you should.

81

Freddie Gibbs & Madlib

Piñata

[Madlib Invazion; 2014]

The recording of Piñata began as an unlikely collaboration between two artists on divergent paths: Madlib had established himself as a producer of such diverse talents that he set himself the task of releasing an album a month throughout 2010 and pulled it off; meanwhile, Freddie Gibbs had garnered hype as a rising rapper, was snatched up by a major label, and just as quickly became a casualty of the game, languishing in relative obscurity during the three years it took to record the album. Gibbs’s situation was so dire that he recorded his vocals while literally living on the streets and fired them back to Madlib, who summoned his crate-digging magic to create an album that weaved thug rap braggadocio with eccentric soul samples. With guest spots from established legends (Raekwon) and artists who would go on to define the decade (Earl Sweatshirt, Danny Brown), Piñata was a classic as soon as it hit record stores (they were still a thing back in 2014, if you’ll recall). The ultimate proof of the record’s status was the ongoing trajectory of Gibbs and Madlib: by the time they reunited in 2019 for the sequel Bandana, it felt like a victory lap from two legends in their own right.

80

Graham Lambkin / Jason Lescalleet

Photographs

[Erstwhile; 2013]

For Photographs, Graham Lambkin and Jason Lescalleet traveled to their childhood homes in Folkestone, England and Worcester, Massachusetts to complete the album trilogy that began with 2008’s The Breadwinner (recorded at Lambkin’s house in NY) and 2010’s Air Supply (recorded at Lescalleet’s in MA). The result was a movie-length examination of the relationship between memory and location, providing an audio verité glimpse into the friends’ encounter with their pasts. As if listening in with a glass to the wall, we overheard discussions about Lescalleet’s tea preferences, Lambkin’s prized banjo, and the olfactory properties of Mexico City as compared to Jacksonville, Florida. In the tradition of Luc Ferrari’s Presque Rien, Photographs argued for field recording’s potential to create immersive soundworlds on the premise that the “world itself” is compelling enough to be listened to. Of course, with Lescalleet’s involvement, the field recordings didn’t go wholly untreated. “Danger of Death” featured a disorienting ear-piercing tone, while “The System” provided three minutes of digital noise. But when counterposed against the lovely choir on “Quested to Saint Hilda” or the gorgeous outro of “CT20 1PS/Rinsing Through the Shingles,” such moments only deepened the impression that this album, like a photograph, contained all the beauty and ugliness of the past.

79

Beach House

Teen Dream

[Sub Pop; 2010]

Would I have arrived without the direction that she indicated by hand. That she folded into a soft edge. Would I have followed her voice around the mirror, into the hum. I knew the sound, even though I could not place it, because it looped and guided me to a wide open field, a hell beneath the stairs. The shape of her mouth deciding whether our bodies would crystallize or recline or bend, depending on the quality of the vowel. You tell me only time can run me. I thought I understood the architecture until something round slipped and rolled into the night. I thought I understood where to coil, where to lounge, where to tear a moment from the days that carry us on forever. Where I might have drawn the curtain and organized the light, I surfaced into a kind of gold that blurred what I could remember about tracing half a circle into thin cotton, ecstatically. Teen Dream made the room warm so that mood could become texture, made the haze, the grain, a ritual. The seam of my dress, the rim of the glass, spiraling. The wing of my eye, the frame, melting into a time I could make glow.

78

Solange

A Seat at the Table

[Columbia; 2016]

A Seat at the Table succeeded and grew deeper with each listen, because it was Solange laid bare: a chunk of her humanity, with all the complexities and messy contradictions, assembled with grace and stitched with anger. On “Cranes in the Sky,” the effortless, pure beauty of her vocals wrapped themselves around laments aimed at the emptiness of her depression. It was this juxtaposition that structured the album. Even “Mad” and its message of both holding on to and letting go of emotions slid by with the ease and simplicity of clouds on a calm summer day. Yes, this album was a statement about race in modern America, highlighted as such on tracks like “Don’t Touch My Hair” and “F.U.B.U.” Yes, this album reveled in the fond memories of lessons from the past (hello, Master P) while also looking forward to a world with greater musical possibilities (hello, “Don’t Wish Me Well”). But what made this album special was never just its individual parts. This album was an encapsulation of all that Solange has been, can be, and is, but it never lost sight of the beauty, ugliness, and complexity of what it means for any human to be alive.

77

Women

Public Strain

[Jagjaguwar; 2010]

Women died an unceremonious, explosive death shortly after the release of Public Strain. It seemed to be a fitting end for a band whose genius seemed almost unsustainable, given how fully formed and peerless their final album was. But the death of Christopher Reimer in 2012 brought everything back into perspective. An unfair, untimely, shitty loss for music as a whole, it is fortunate that we have Public Strain to remember him by. The album stands as a perfect summation of his virtuosity, a true guitarist’s record, vast and expansive, grasping at new sounds and eager to explore riffs with cool curiosity. There are few rock records that can unite drone and pop so fruitfully, flitting between bold experimentation and crowd-pleasing melody, but Women straddled that line with stunning ease. Simultaneously warm and frigid, calculated and emotional, Public Strain was simply an indefinable treasure. It now sits in the annals of classic post-punk records, new and experienced listeners alike lucky to uncover its hidden secrets.

76

Chief Keef

Almighty So

[Glory Boyz Entertainment; 2013]

Chief Keef foils the list-maker like no other. Bang, Part Two signalled a hard left into a genre all his own, and for all the linear, phased creative development he’s undergone since, no two releases fail to resist comparison (to one another, let alone to anything else, to say nothing of the ever-shifting mass of snippets and loosies that comprises seemingly half his body of work). Almighty So isn’t a bad place to start, though. Something like a Rosetta Stone for Keef’s mid-decade output, the mixtape foreshadowed the ear for production that Sosa would soon take into his own hands, the pop predilections that would congeal into the much-delayed but once-contemporaneous Thot Breaker, and the leaned-out sensibilities that would resurface in his present “underwater” period (which, purportedly, will deliver us Almighty So 2 any day now). While the urgency of simply getting familiar with Keef dwarfs the importance of the specific point of entry, why not Almighty? As Sosa fandom has narrowed (somewhat) and deepened (near-religiously) over the course of the decade, no tape’s appellation has proven more prescient. All hail!

75

Eli Keszler

Stadium

[Shelter Press; 2018]

Eli Keszler’s musical career has been built on expanding the vocabulary of percussion, and with Stadium, the experimental drummer and sound artist crystallized his clearest vision yet. From the breakneck pace of opener “Measurement Doesn’t Change the System At All” to the cloaked ambient textures of the provocatively titled “We Live in Pathetic Temporal Urgency” to the synth-led “Fashion of Echo,” Keszler placed tendrils of jazz throughout the entire album. Was the gorgeous drone that kicked off “Was The Singing Bellowing” the work of meticulous field recordings, multiple stompboxes run in series, or a combination of both? How about the genesis of the broken beat that propelled “Simple Act Of Inverting The Episode?” You could take a guess at what the influences were (maybe if Cid Rim got together with Jon Hassell?), but the tunes resonated inside entirely uninhabited territory. Having produced several large-scale art installations outside of his music project, Keszler has understood for years the uncanny spaces that sound traverses, and nowhere was it on better display than on this outstanding record.

74

Angel Olsen

Burn Your Fire For No Witness

[Jagjaguwar; 2014]

Floating our way midway through the decade like some eerie-ass fog off some swampwater, the sophomore effort from Angel Olsen somehow rendered the heaviness of existential dread and the messiness of constant anxiety sheer and weightless. Indeed, just like a gaseous vapor, it felt like a beguilingly uniform affair: no track was a highlight, because no track was a lowlight, either. More significant to its place in history, though, is the fact that, by the time the last of this album’s ambiguous-yet-personal lamentations had ended, Olsen’s quavering, confused-but-confident howl proved we hadn’t heard NOTHIN’ YET. It’s easy to forget it here at the end of the 2010s — now that her songs have fully ascended to the heights of full-on electro-acoustic oratorios — but Burn Your Fire managed to stubbornly exist in that dizzyingly low-oxygen “Goldilocks Zone,” wherein both her vocal range and instrumental palette took ramshackle steps forward from the sparse mumble-folk of her debut but hadn’t yet reached their terrifyingly confident, pop-diva potential. Here on her debut for Jagjaguwar, Angel Olsen didn’t yet know how to tear her way into our hearts with countless elaborate and glimmering hooks. So she did it the old-fashioned way: with 11 rusty fish hooks.

73

Panda Bear

Tomboy

[Paw Tracks; 2011]

Before I was a critic, I was a chorister. Which means that I sound things out instead of pinning them down, and I know that can make me hard to follow. But let’s not pretend that the density of a call across rooms in a home you know fondly doesn’t tell you things its diction can’t. Or that the difference between silence and hush burnished and lucent isn’t a messianism of sorts. Even the imprint of a body on a bed or the contours of the palm on a handmade bowl could adumbrate the forgiving carpentry of a sacristy if the touch is tender enough.

Now I see you again

Now I feel you again

Now I know you again

Tomboy is expanse. The vastness of your uncle’s snug embrace or the last note you heard Thomas sing before you grew apart and he died in his mother’s house a couple weeks before you both were supposed to turn 21. But only one of you did, and time’s profanations elongate your distance to his rude and rapturous colophon. When I slammed my finger in the car door and moved prematurely to the alto section, Mr. Brady told me to hold my horses: I’d miss my head voice soon enough. I can’t sing like Noah Lennox anymore.

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

I know I know I know

Conventional wisdom crumbles bitter in the mouth, but artless smiles stay, yawning broad like dad’s shoulders or the hymnal breath shared before a kiss. Everyone knows what they say, but it’s clear now how it’s what they don’t say that counts. Sometimes a voice refracts indefinitely, marking every surface it osculates in its weft of gentle intimacies. Sometimes the louder a voice is the more it amplifies the quiet gossiping of its sonic substrate: the muted bray of the congregation at evensong or the windblown howl of the benfiquistas chanting for Óscar Cardozo in his gangly prime.

Don’t break ties that hold them

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

Don’t break

After “You Can Count On Me” unfurled into so many voices, silence, properly speaking, ceased to exist. There is always and there is only chorus.

72

Matana Roberts

COIN COIN Chapter One: Gens de Couleur Libres

[Constellation; 2011]

It was her saxophone, screaming alone, that shattered the silence. This first gripping sound of Matana Roberts’s 12-chapter COIN COIN project — named after freed-slave-turned-entrepreneur Marie Therese Metoyer — threw us into one of the most conceptually ambitious, sonically captivating, emotionally raw musical odysseys of the decade. The Chicago-born saxophonist and composer, employing graphic scores and practicing a technique she called “panoramic sound quilting,” assembled a 15-piece ensemble for this introductory installment of her multi-part exploration that combines personal ancestral narrative and the broader African-American experience. In a historical moment when dwindling attention spans sparked a billion unread think pieces (and skipped podcast episodes), and the relevance of albums for many declined (once again), and even the celebrated ephemerality of pop songs started feeling like a grueling eternity (because what would the algorithm recommend next?), Roberts went unapologetically, no-fucks-left-to-give LONG. FORM. It was timely and untimely, personal and political, beautiful and violent, all at the same damn time. In 2019, to wrap the decade, Roberts delivered the magnificent COIN COIN Chapter Four: Memphis. At this pace, we can anticipate two more decades of COIN COIN. Twenty more years of inspiring, edifying, and courageously unpredictable music to look forward to.

71

Frank Ocean

channel ORANGE

[Def Jam; 2012]

Funny to think about the world when Frank Ocean was just another Odd Future affiliate. Sure, the crooning-over-others’-beats mixtape nostalgia ULTRA showed promise, but Christopher Breux did not truly become Frank Ocean for many of us until channel ORANGE’s second single “Pyramids,” a nine-minute prog’n’B banger with a filthy extended John Mayer guitar solo. Goddamn if those first synth stabs don’t still get me riled the fuck up! What’s stunning is how well channel ORANGE holds up years later, even as it’s been eclipsed by the perfect Blonde, the if-you-blinked-you-missed-it Endless, and a host of non-album singles evidencing Frank Ocean’s brilliance. But this one’s just as important to the story. It’s easy to forget how significantly the sound of R&B has changed from 2010 to now; perhaps nobody carved out the contours of that change more than Frank. Get into your time machine and maybe you can find your way back to the date Frank published his infamous “thank you’s” Tumblr letter — oh wait, thanks internet! — a landmark development in the way we discussed blurred gender and sexual identity in rap and R&B, and truthfully the world. It was also a transformative moment in our collective relationship with Frank. Now, we felt, we knew him. For real. And the music on channel ORANGE became something more, something vital for so many of us, as we explored all of the ups and downs of this crazy life. Because somehow, it seemed, Frank knew us too. So no, Frank… thank YOU.

70

Giant Claw

DARK WEB

[Orange Milk/Noumenal Loom; 2014]

We have no time for anything anymore, so we demand everything all at once. As information from all corners of the corporeal and incorporeal worlds course through the cyberculture at ever-climbing rates, any authentic aesthetic discrimination seems more and more an impossible task. Attention takes its place as the highest commodity, and algorithms work tirelessly and silently to map our psyches according to how we invest (Besetzung). Moreover, as all these signifiers, familiar and unfamiliar, fly past us too quick to catch, maybe too quick to even see, they become alien and incomplete. We have more content than we know what to do with, and it’s killing us. Released at just about halfway through the decade, Giant Claw’s DARK WEB was something of a saturation point — it signified the primacy of a cultural thinking that was too expansive to contain itself. Just look at that sphere on the cover, burst open and oozing, slathering our so-called culture with its vital pulp. However, this spilling out was not some unmoored anarchy of thought and sound, but, as Adam Devlin suggested way back when, it allowed DARK WEB to behave as a restorative for our hypercaffeinated condition, congealing its chopped and aerosolized R&B vox, trap hits, and carnivalesque MIDI pomp into some sweet, strange medicine. What Keith Rankin did here was a working-through and a making-sense of what it means to truly have the world, in all its immense teratical glory, at your fingertips. In that sense, DARK WEB was a true slice of the sublime — encounters with an ineffable internet sliced and rendered down into something we just might be able to eff with.

69

Lolina

Live in Paris

[Self-Released; 2016]

Monopoly’s first iteration was named The Landlord’s Game, a brainchild of Lizzie Magie who in 1903 set out to create an educational tool to model the ill-effects of wealth consolidation and rent exploitation. Magie lived during the height of the Progressive Era, a reactionary movement that sought to eliminate corruption and address the problems wrought by industrialization. Magie and her peers lobbied for more government regulation and more public ownership of land and other capital. Fast forward a century to the 2010s, a decade in which wealth inequality soared, political corruption and election tampering became the norm, and the world began to enter a state of economic transformation not unlike the early years of Industrialization.

It’s fitting that, over a century after Magie first postulated The Landlord’s Game, Lolina (a.k.a. Inga Copeland) would settle on Monopoly as an aesthetic referent for her politically-charged 2016 performance in Paris for RBMA. Like Magie so long ago, Lolina’s performance subtly explored the ill-effects and dangers of exploitation and wealth consolidation amidst globalization and immigration. The audience was quite literally immersed in Monopoly (projected onto larger-than-life screens), as Lolina soundtracked the board itself with a genre hodgepodge bordering on directionless, with everything from playful melodies to hammered synth loops to random soundbites to cuts from her previous albums. Most of the board’s squares contained London landmarks, but the performance’s implication(s) could have been applied to any number of major cities. As the “game” approached its climax, plastic houses sprouted across the board indiscriminately, suffocating the squares before bursting into flame.

It’s difficult to conclude there were any overt political inscriptions woven into Lolina’s performance, but whether she intended to or not, she provided an important conceptual space for us to contemplate globalization, the 2016 election, Brexit, the 2015 Paris attacks, eco-crises, and all the other seemingly insurmountable political catastrophes that the 2010s bestowed. Lolina inflected her art with ambiguity, seldom a reach for the particular, but rather a vague motioning toward the undetermined. Here, she directed our attention to the delicate precarity of our condition, and she did so with a sigh of calculated simplicity.

68

Colin Stetson

New History Warfare Vol. 2: Judges

[Constellation; 2011]

I once saw Colin Stetson play solo in a jazz club in Dortmund, Germany. I guess Jazz Time is different from Rock & Roll Time, or the Germans’s reputation for timeliness is correct, because the ticket said 8:00 and by God they started at 8:00. This was unheard of in the American rock bars that I was used to frequenting. So I got there late. Perhaps this was for the best, because the effect of opening the club doors into a wall of sound coming from a solitary man onstage couldn’t have been planned. The audience remained Germanically stoic until the last blast from Stetson’s bass sax faded away and, after a pause, someone in the back of the room said “Wow.” There’s really no other proper reaction to Stetson’s playing, which he perfected for New History Warfare Vol. 2: Judges. Stetson placed contact mics strategically on his horn and on himself, which picked up his superhuman performance to create a full band’s worth of noise. For this outing, Stetson invited Laurie Anderson and Shara Worden to perform vocals that describe the terrors of war, just in case he alone wasn’t loud enough to evoke the same. He needn’t have worried.

67

18+

MIXTAP3

[Self-Released; 2013]

MIXTAP3 was an exoskeleton with the vulnerable innards included. Bright and dark, cold and warm. It was streaks of spit and sour breath on avatar skin. It was ringtones and heels clicking in an alleyway. Chords and notes trailed like lamplight. Boy and Sis moved with wolf smiles and soft hand, their breath percussive through unconsciously relaxed jaws. Eyes shifting. Their words were equal parts dismissive and full of longing, like a fuck-site profile come to life. It was easy to visualize the pair nodding to every beat, slowly twisting thumb rings in a corner. Alone and watched. But physicality isn’t gospel. What MIXTAP3 explored and facilitated so perfectly was the lift and tilt of persona, what could be expressed and unseen.

66

Grimes

Visions

[4AD; 2012]

It’s so easy to forget now. Especially now, when you have a bullshit job where you want to tell the boss to fuck right off and wipe that shit-eating smile off his lackey’s face. It’s easy to forget that once you could feel something with music. Feel a lot more than distraction, or mere admiration. When music was your blood, more than anything else. A good beat, a good voice…that was enough to forget about everything else and remember who you are.

I know you’re faced with something that could consume you completely…

Music has been so much to you. It’s given you life, it’s brought you closer to your friends, your family, the ones you loved. It has given you friends, for fuck’s sake. Have you forgotten that?

You could be a better friend…

But now you remember. You remember what C told you to begin it all: Shut. The. Fuck. Up. Even now, years after you played this, you still feel something greater than you understand. The dynamics have changed, with so many gone and moved on. [So many yielding to despair like it was trendy]. Don’t… no. I know you won’t give in.

I know the way (I don’t know the way…)

That’s right, remember. This. Is. Not. You.

65

Titus Andronicus

The Monitor

[XL; 2010]

Like most people of this generation, my first exposure to Titus Andronicus was, of course, when the blogs posted about them performing “A More Perfect Union” on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. Of course, that led to seeking out The Monitor in full, which led to realizing “A More Perfect Union” was actually a seven-plus minute anthem that opened an exclusively anthemic album, followed by thoughts of “what’s all this about the Civil War now?” and then ultimately culminating in this next thought that is concise yet said with complete confidence after all this time: The Monitor is a masterful album. Set against the backdrop of one of history’s greatest internal struggles, the album dug in on all kinds of personal internal struggles that have come to, in part, define this weird decade. How can we solve any of the world’s problems when we can’t even solve ourselves? Is this still a war we can’t win? After 10,010 years, it’s still us against them, still us against them, still us against them, and they’re winning. The key to surviving, though, is to keep the fight alive, regardless. “You’ll always be a loser and that’s okay.” Scream it until you can’t anymore. Rally around the flag.

64

Jeremih

Late Nights: The Album

[Def Jam; 2015]

Sardined centrally in a crush of clubbing bodies; the Uber should be here by now; we couldn’t get out of that summer rain. Listen to me: I’ve been working on a list of situations not improved by Jeremih’s Late Nights: The Album, and the list is short. Jeremih’s salacious R&B was so effusively infectious that every second of it displaced the right now with a pulp of phased-out memory, real and imagined, warmed and cooled by effervescent bisexual lighting. Blame it on the drink, baby. As late, late night blurred into early morning, as drink flowed and intermittent trysts came and went, Late Nights slid from the crystal heights of “Planez,” to the stumbling clatter of “Give No Fuks,” to the woozy womp of “Woosah,” into the next-morning migrained clarity of “Paradise.” Don’t worry what time it is. All your friends are still here: Future, YG, Migos, Big Sean, Jhene Aiko, Juicy J, Twista. No one’s going home; no one’s running behind. On Late Nights, every hi-hat split itself into triplets, every backbeat was the flick of a lighter, and every sinuous inch of melody was so pure that it was hard to imagine a time when it didn’t exist.

63

Charli XCX

Vroom Vroom

[Vroom Vroom; 2015]

Charlotte Aitchison always had a good ear when it came to diversifying her production. But before Vroom Vroom (and despite her involvement in some absolute classics), she struggled to find a consistent sound that could match her persona. And then along came SOPHIE. While this marriage of pop powerhouses was perhaps inevitable, it was still really cool when it happened. Vroom Vroom looked like a lap dance in latex, smelled like perfume and sweat, tasted like Red Bull and vodka, and felt like grime and chrome. And it sounded like the future. SOPHIE’s production was dynamic and energized, but Charli herself is the reason we’re still talking about this EP. She flowed seamlessly from pleasure-seeker to provocateur, displaying the confidence of a pop diva at the top of her game. With a trunk full of the best beats and hooks of the decade, Vroom Vroom was Charli XCX behind the wheel of a lavender Lamborghini, parked and honking outside your house, as if to ask if you were game enough to come along for the ride.

62

Aaron Dilloway

Modern Jester

[Hanson; 2012]

Emerging from an immersive, cultural shift, Modern Jester was conceived several years after noise proliferator Aaron Dilloway left his home in the US and spent several months collecting field recordings in Nepal. The way in which that overseas experience directly impacted his approach to production here is unclear, but the very thought of tackling a creative outlet after spending a prolonged period in new environments is exciting at the best of times, let alone when left at the hands of such a staunch and expressive practitioner. Modern Jester came way after Dilloway’s impeccable Sounds of Nepal series, but the frantic and coarse approach to field recordings could be heard all over the latter release, as it drew on musically diverse and abstract themes: automation, repetition, fear, isolation, desperation, and havoc. From the 18-minute cacophony of “Look Over Your Shoulder” to the berserk frenzy of “Tremors,” Modern Jester exemplified the sheer breadth of possibility within creative composition while remaining aligned to a core aesthetic. Every listen conjured a range of emotional responses, which felt as though they were based on direct experience — from Nepal or otherwise — and even now, Dilloway’s berserk masterpiece remains utterly unparalleled in both ambition and audacity.

61

Jessy Lanza

Oh No

[Hyperdub; 2016]

Jessy Lanza rides a bicycle in the music videos for “Oh No” and “I Talk BB,” released about a year apart. In the former, she emerges from the fluorescent light of an underground parking garage to the dark streets above, where she, her reflective jacket, and the pavement below are lit by the flashing, multicolored lights woven through her shocks. There are signs of life around her — some distant traffic, a customer loading up his car with groceries — but all of the attention is on Lanza and her psychedelic ride. Eventually, her environment begins to distort and fall away, like in the moment at which the viewer becomes one of her wheels, and the world turns into a spinning void. The video for “I Talk BB” has more pathos; from close range, we study people and animals, couples and individuals caught up in their interior worlds, and other engaged in their own forms of commute, all bathed in diffuse sunlight as Lanza passes them by on her bike. We see stock images of smiling families and professionals plastered on shop windows and benches. On Oh No, Lanza’s ecstatic pop takes you on both kinds of ride: it can be chaotic, obscure, and subjective, or it can be bright and empathetic, putting you in touch with something outside yourself. Here, Oh No is not an exclamation of horror or disappointment; it’s giggled with tentative excitement, like a reaction to something thrilling and unfamiliar.

60

Klein

Tommy

[Hyperdub; 2017]

Love & hip-hop: Atlanta — that’s, like, a reality TV show, right? Yes, and it’s also electronic artist Klein’s backstory for her debut album on Hyperdub. Beyond providing a title and a source for sound samples, the show’s bad-girl guest Tommie Lee served as an archetype of obstinance: “What would Tommie do,” Klein mused in an interview, “like, she wouldn’t even care.” Likewise, three albums into her own career, Klein showed little interest in playing sweet with the powers that be. Recorded primarily in her bedroom, Tommy was as volatile as its namesake’s reputation: gaseous piano chords looped over fractured beats, blasted by noise, then smeared into opaque drones. Whether crooning or chanting, Klein sang wordless alleluias chapeled in her body, riffing across scales with gospel exuberance. Produced with an ear for entropy, Tommy thrillingly bridged two separate worlds, the musique concrète tactics of Pierre Schaeffer’s avant-garde with the vocal prowess of Billboard R&B divas. But unlike her plaque-chasing peers, Klein has better sense to save her walls for family portraits. Real gold, as Klein well appreciates, can’t be won by committee vote. It doesn’t sparkle so brightly — or so easily.

59

Low

Double Negative

[Sub Pop; 2018]

On Double Negative, Low had successfully pulled off a feat few recording artists would’ve dared entertain for a 12th album in a 16-year-long career: they’d transposed the essence of what made their music different than anything that come before into a sound both fresh and contemporary. In Low’s case, what that meant was putting the bewitching vocal harmonies of founding members Alan Sparhawk and Mimi Parker through a metamorphic treatment of heavy digital processing, chopping and twisting and then ultimately placing them against an indescribable, half-instrumental, half-synthesized backdrop that clattered around as if molded from static alone. On the one hand, listening to the album was akin to discovering a decaying Disintegration Loops-like residue of a musical past, which was somewhat cheekily making the self-deprecating point of the datedness of Low’s world; on the other, Double Negative offered a blueprint for veteran artists whose spirit had not gotten old but whose expressions could use a facelift. More than anything, though, the album belonged: to Low’s awe-inspiring legacy, to a post-genre musical landscape, and to a world that increasingly felt like a disintegration loop itself.

58

Jam City

Classical Curves

[Night Slugs; 2012]

Classical Curves was the sound of a new world in the process of creation. Released in 2012, it thought through the emerging aesthetics and politics of the post-recession: a world in which decay was made structural, where collapse was folded into “growth.” It made visible the wreck of neoliberalism, its primal scene, endlessly repeated — buildings with pools and doormen in a state of constant tumescence, accompanied by homeless people round the corner, always kept out of sight. In Jam City’s native south London, Classical Curves sounded like “regeneration,” the flattening of specificity to make way for a verticalized generic. In its jackhammer beats, we heard the demolition of shopping centers, the exile of local communities, their making way for dull flats, lifeless gyms, and bad coffee. These losses wrapped themselves around Classical Curves, making themselves heard in its vocalic synths, their sighs the echoes of lost worlds. No mere exercise in late-capitalist fetishization, then, Classical Curves wanted to move us. It wanted to make us dance, and in so doing, it wanted to make us think. In its elegantly-shaped empty spaces, in the uncanny funk of its mechanized movements, and in its provision of a shape for pop to come, Classical Curves developed a sound that helped us understand where we came from and where we were going. This was how we related to our bodies, our clubs and our cities in the deadened hyperreal zones of the 2010s.

57

U.S. Girls

Half Free

[4AD; 2015]

Eight songs and a skit was all it took. Despite its brevity, Half Free felt enormous, genreless, miragelike. Its production hit a pleasingly foggy mid-fi sweet spot, overcast, suggestive, noirish — an appropriate objective correlative to the stories its songs contained, populated by dead soldiers’ widows, familial cruelties, and strained spouses, all told first-person. These were stories, all of them, about women wronged by men, or left behind by men, or contemplating vengeance upon men. The eight songs played around with as many genres, tied together by Meg Remy’s voice and almost country-esque command of sung storytelling. The heart of Half Free, though, wasn’t really a song at all. It was “Telephone Play No. 1,” the minute-long Rorschach blot of an interlude that stopped the album after two tracks. With each listen, it could reveal a new meaning, and yet it was the hardest thing on the album to listen to, the aural equivalent of the very bright light an optometrist shines into your pupil to look at the back wall of your eyeballs.

56

Triad God

黑社會 Triad

[Presto!?; 2019]

NXB, the full-length start to the partnership between London via China via Vietnam MC Vinh Ngan and experimental electronic pop producer Palmistry, had all the markings of the unique aural aesthetic the two would decide to stamp the name Triad God squarely on. It was 黑社會 Triad, however, following after seven years of near-radio silence from Ngan, that took that aesthetic and turned it into a sublime, unprecedented sound artifact of crushing immediateness and bewildering beauty. On 黑社會 Triad, Palmistry’s minimal synth melodies and deconstructed hip-hop beats dissolved into digitized operatic yowls and towering ambient vistas, while Ngan’s lethargic, mostly-Cantonese rapping became full-on confessional poetry, delivered via fragmented, half-awake monologues. As the album progressed, the two sources of sound and substance became increasingly desynchronized, to the point of their co-existence appearing less like music and more like a field recording of a very real, very painful moment in someone’s life. Listening to vignettes such as “So Pay La” felt like having your friend suddenly pour their heart out to you in the wee hours of a Sunday morning, when you’ve had way too much to drink and can’t wait for the person working the kebab stand to call out your name. You don’t understand half of what your friend is saying, but the gravity of the moment hits you just the same. And then you listen.

55

Drake

If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late

[Cash Money/OVO; 2015]

And, just like that, Napoleon crowned himself. Finally endowed with the heavy airplay (all day / with no chorus); laundry list of famous exes; and, well, bands that a young Aubrey had always flirted and fantasized and fronted about, Drake emerged on If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late as an a priori. No longer just my homie over there who think ur cute, the perpetual aspirant already unconvincingly flexing with Nickelus F on Room for Improvement, Drake could finally stop orbiting every possible influence, opportunity, and storyline and let his own tumid gravity constellate his place in the pop/rap cosmos. The self-styled (for how could it be otherwise?) 6 God looked good as a celestial body, his stardom as unassailable (though truly nothing was the same with dude after Sauce Walka ethered him — OOWEE!) as it was inaccessible. None of which is to say that Drake’s hard-won iconicity licensed empty simulation, the stuff of media studies undergrad dreams; if anything, If You’re Reading This demonstrated why Drake’s corpus of pastiche and reference, a seriously jacked body with seriously juiced organs seemingly cobbled together out of logos and other simulacra, commanded such fervent brand loyalty. On display in If You’re Reading This were Drake’s unmatched powers of curation and customer service, his perfectly calibrated sensitivity to the affective life of human capital in a rapidly and rabidly freelancing world pivoting to video. Because who else other than the internet’s busiest simp could demonstrate how performative disavowal is no match for the architectures of desire goading our most egregious and mundane fantasies? Sorry Jenny Holzer, Drake isn’t going to protect you from what you want. He is what you want. Oh, you gotta love it.

54

Jason Lescalleet

Songs About Nothing

[Erstwhile; 2012]

With its cheeky concept and punny track titles, one might be tempted to assign a type of theoretical gravity to Songs About Nothing, casting it as some high-level comedy of deconstruction. One might be impelled to hunt down traces, quaff some pharmakoi, and split the différance. And that’s all well and good. Discourses about appropriation, decontextualized sound as plastic, politics of pastiche and irony, metaphysics of presence, decay and deformation, being and not-being: each potentially generative avenues of exploration into Jason Lescalleet’s monumental work. However, we don’t need to distract ourselves with what is external — Songs About Nothing stood alone populating the void, in defiance even of its own title and network of samples, references, and appropriations. Great buzzing existential meatsaws scourged its 76 minutes and shred all stable signifiers within. Whether it was the Big Black samples stretched and savaged and smote completely; the sounds of birds, trucks, protests, and helicopters; or the low, insinuating tones encrusted with digital manipulation, the corruption, the destruktion, was total. There were no little ditties or ambient soundscapes, just obliviated airs and anti-environments. While, of course, no thing can be about nothing, it was difficult to escape a sense of vacuum here, an inert core around which Lescalleet had constructed his capital — gleaming spires of nullity and broad boulevards of implosion. It was equally difficult to visit that place without at least carrying back the faintest whiff of annihilation.

53

Lorde

Melodrama

[Republic/Lava; 2017]

What is this tape? The tape was Lorde’s album-long ode to the passion of youth and the beauty of destruction. It was a generational statement. Maybe I was a generation behind, but none of that mattered. I fell in love with this tape — its dazzling synth lines, introspective hooks, and Instagram-ready lyrics. No other pop record from this decade better captured living fast and dying young. Whether it was blowing her brains out on the radio or ending up painted on the road, Lorde (like so many singer-songwriters before her) distilled her experiences into universally relatable moments. This was what it felt like to be a 19-year-old in the 2010s. It felt like staying up late, alone in the dark, writing something. It felt like being the only person on a subway car full of strangers. It felt like something slipped under your tongue, the excitement of telling a friend that that one person texted you back. It felt like you were on fire. And this tape was worth sharing with someone you love so that your fires could feed on one another, burning brighter and fiercer. So what is this tape? This is my favorite tape.

52

Kendrick Lamar

good kid m.A.A.d city

[Top Dawg; 2012]

Are there any words that have yet to be spilled about the major label debut from one of the most popular rappers working today? Perhaps it’s worth honing in on the fact that good kid was personal and emotional, serving as an entry into a mainstay genre that isn’t frequently known for either of those things. Kendrick wasn’t immune to the characteristic bravado, but while that personality trait permeates among rappers seemingly out of career or cultural necessity, what we had on the album was a retrospective on youthful misguidedness. The machismo reflected on “Backseat Freestyle” isn’t who Kendrick is today, and similarly, the robbery described on the subsequent track, “The Art of Peer Pressure,” isn’t used as a feather in the cap by present-day K-Dot. It was clear as things progressed, and certainly by the end of the album, that the Compton native was more concerned with describing the mindset, commonly errant and adjacent to tragedy, that he had growing up in the 1990s and the 2000s. Clever flow and consistent production helped deliver self-awareness to listeners. Even most TV shows don’t have this level of character development.

51

Shabazz Palaces

Black Up

[Sub Pop; 2011]

It’s difficult for me to address Shabazz Palaces historically, because they initially struck me as an aberration. Overshadowed by a residual “O.G.” politics, their earliest EPs felt just a little too stiff, too needlessly esoteric, for me to fully enjoy, like a pre-Wu Genius close-reading Farrakhan. And aside from pulling the obvious “hipster rap”/backpacker card, calling these guys “old school” was probably the biggest diss you could lob; Ishmael Butler clearly wanted to do something different with his resume. So, hardly rejecting their posture’s awkward inconsistencies, Shabazz Palaces’ 2011 debut album Black Up pretended a subtle homage to the debased currency of youth. And it worked, all because it hinged on risk and diversion. I say risk because who, exactly, was clamoring for this kind of album in 2011? Who, exactly, was Shabazz Palaces for, aside from maybe Butler himself? Despite their continued presence and with the benefit of hindsight, I’m still not sure I know the answers to those questions, and I don’t want to pretend I do. Ultimately, it’s easier to define this album by what it wasn’t, rather than what it was — and it certainly wasn’t Take Care.

50

Julia Holter

Loud City Song

[Domino; 2013]