We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

20

Scott Walker

Bish Bosch

[4AD; 2012]

Although Scott Walker was reclusive and disinclined to give interviews, those that are available to us showed a genial, good-humored human. Nonetheless, Bish Bosch, 2006’s The Drift, and 1995’s Tilt have cast a remarkable pal over their respective decades. They stood apart from other significant works of their time both by design and by their innate refusal to wed their eloquence to mere elucidation. These albums reported on alienation so profound, so far flung they felt like urgent, immaculate, yet hopelessly tangled transmissions from purgatory. One can repeatedly look up the words “macaronic,” “mahout,” and “mascon” and still find no illumination. Every line a shining, austere forgone conclusion, all the more dazzling for its elusiveness. He may’ve been light and jocular with Jarvis Cocker, but the work showed a stridency and obsessiveness that screamed to the listener. Not for help, but just to have someone to scream to. Like the bizarrely hilarious, churning “Epizootics!,” abject isolation has a terrible momentum to it. It’s perhaps safe to say that if Walker didn’t find a place for this momentum, he’d have been lost to us like Syd Barrett after that first dandied blush.

But we didn’t know the man 2019 took from us. One can recognize the liability of seeing and interpreting without interacting. The acute sensory realm of this trilogy notwithstanding, the music could take on this draggy sort of weight. And yet you gotta hate it when people say “it’s called depression” in a dismissive way. Besides it being simply reductive, it slams shut the doors of lateral moves (a.k.a. creativity), which save us from fully succumbing to despair. These albums represent the pinnacle of this creativity at its most relentless. And the remnants of the crooner’s former teen idol self became hardest to grasp on Bish Bosch. The soul, or pained lamenting, of that previous life gradually gave way to glib, sneering pronouncements over a cluttered dissection table. In both phases, there seemed a tactical emotional detachment, but this was only a means for Walker to better get to something more genuine.

Just as the 1960s and 70s showed Scott Walker to be a willing, ambitious pop interlocutor, these albums showed us a sizable void of endless relief on the other side of fame’s dogged obligations. While not strictly fear-exploiting, these albums were only pop in the sense that a horror film is. And Scott coolly escorted us through these nauseating, dispiriting, and alarming scenes, nowhere more Crypt Keeper-esque than on this album (unless one counts the 2014 Sunn O))) collaboration Soused, which can’t help but feel a bit like an addendum). There was a dry giddiness that both buoyed and ballasted the audience’s sinking feelings. It may’ve elicited some uncomfortable laughter, but a choking vast crush of space soon followed. And it wasn’t hard to see those pitted glaring eyes of his in those moments. You knew that he was a vessel in those moments, that “elegant” is transitory while “explicit” is definitive. The rubberneck field notes were laid out, and authorial distance didn’t soften them (even on the gorgeous, desiccated closing ballad, “Conducator”). The crude, evergreen armchair dismissal of what gets called “provocative” as “rubbing one’s nose in shit” seemed a relative phenomenon to Bish Bosch. Having provoked this sort of defensive counter-provocation among disillusioned fans of his early work, Walker only seemed to restrict his Id less, wringing purple spits of off-puttingly tactile verbiage into his drone and clatter.

Scott Walker prized the text first and foremost, and the urgency of having words matter puts him (plus the seriousness of much of the subjects he writes about) much in line with equally vital neo-conceptual artist Jenny Holzer. In times of shrinking attention spans, abstracted, pithy language became less an obfuscation than a lunge away from glazed, transactional impatience (since we all have glowing rectangles behind our eyelids, Holzer often infuses her text pieces with LED lights). Walker obviously adored language, and his exuberant fetishization of it was contagious. Reclusive though he might have been, he managed to be quite the boon to other brave souls who endeavored to meet him half way and listen. These last four albums may serve as poetic testaments to the elaborate wretchedness of humankind, but it was delivered in a way that felt more hale and hearty than usual for this sort of thing. A more comprehensive consciousness of the physical and temporal world around one may have a mighty sag to it, but Walker heaved a glad shoulder and found a mesmerizing gait. Bish Bosch fleshed out our latent existential woes, but once through, he flushed them out as well. Both a purgative and arresting (his voice remained elocution personified) experience, this album was nonetheless probably the least replayed favorite of many (this writer included). But as in previous decades, Walker had a way of cutting through the drowsy haze of moodiness or casual preference and right to a never-convenient, always-essential absolute.

19

Oneohtrix Point Never

Replica

[Mexican Summer/Software; 2011]

Change is the inevitable failure to repeat the past. We are so bad at repeating the past, at replicating the same thing again and again, so as to create a reassuringly familiar simulation of our past lives and selves. We always fail, we always make mistakes, but in the process we create the future.

This is the temporal drama Oneohtrix Point Never played out in 2011 on Replica. The producer’s fifth album, its most distinctive feature was an almost anal repetition of the same set of micro-samples, drawn largely from television commercials of the 1980s and 90s. Most of its 10 tracks stuttered, skipped, or stammered with the sounds of fragmented keys, incidental noise, beats, and vocals. Virtually all of its samples were rendered unrecognizable and uncanny by their truncated lengths. But more importantly, while each replicated mini-phrase was usually identical with its predecessor in purely sonic terms, each repetition created a new context, thereby altering each sample’s resonance and meaning, separating it incrementally from itself.

This process of separation was enhanced by Daniel Lopatin’s increasingly mature and sophisticated production. Washed-out, floating synthesizers were superimposed and wafted over the juddering samples, inflecting them with a profound sense of mourning and loss, highlighting their failure to retain the same significance, illuminating their passage from the same to the different. Lopatin talked in interviews about the idea of the replica as a way of coping with the decline of human knowledge, but the music on Replica spoke to much more. It was the sound of culture changing in the failure to reproduce itself, of society changing, of individual identities changing, of DNA changing.

Replica, then, was an album about the impossibility of replicas. Yet this impossibility was a necessary precondition for the evolution of life and for history, which is why the album was and still is as beautiful as it is fatalistic. Tracks like “Andro” and “Submersible” drifted nebulously, pregnant with creation and an irrepressible suspicion of possibility, each additional sample or chord always invoking something much bigger than itself. Other tracks, such as “Power of Persuasion” and “Nassau,” accumulated poignancy and weight with each stubborn loop, unfolding new sensations despite the ostensible duplication of source material. And, at all times, the mortal failure to reproduce an identical copy of what came before could just as easily be heard as a victory, as a liberation from codes, conventions, and precedents.

Yet despite its conceptual depth, Replica was as much a stylistic and aesthetic triumph for Daniel Lopatin as anything else. Pushing him away from the synth-heavy coldness of Returnal and previous albums, it took the chopped & screwed blueprint laid down by his 2010 Chuck Person’s Eccojams Vol. 1 mixtape and transformed it into a deeply coherent and unified artistic statement. It may have been arguably non-musical in its obsessive repetition of sub-second samples, but it created in the process an incredibly unique way of finding significance in sound, as well as significance in our all-too human inability to preserve the past inviolate.

18

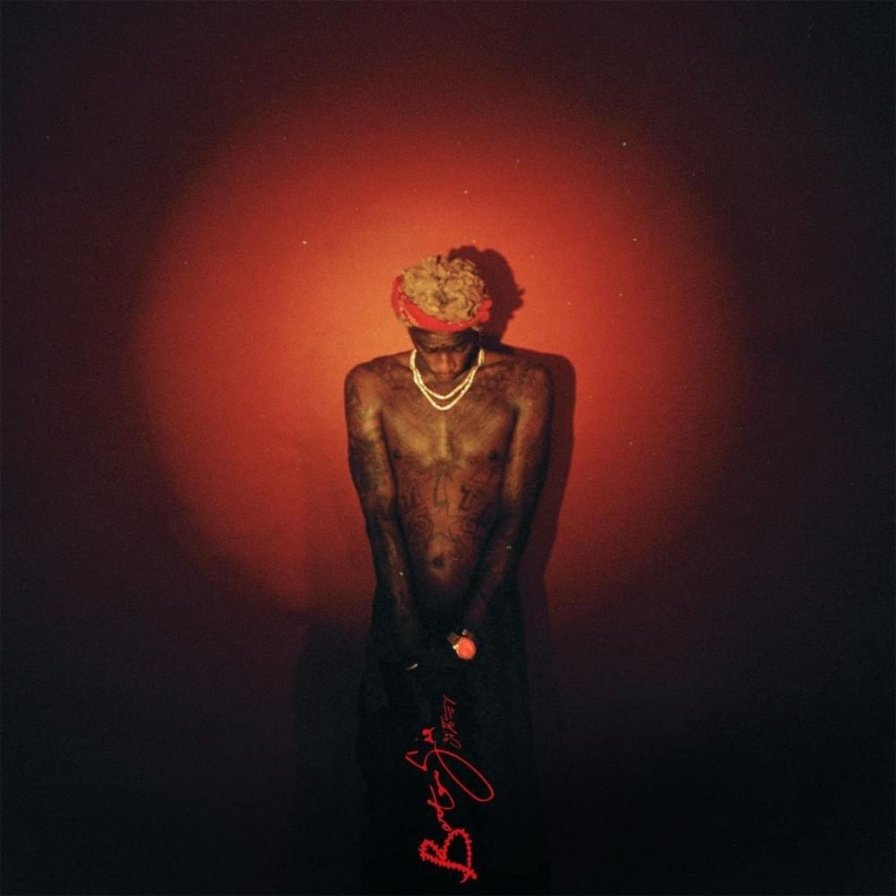

Young Thug

Barter 6

[300; 2015]

What remains to be said about Young Thug? Sonically, his style has become something like a joke that loses its magic through over-explanation (I imagine Lyor Cohen can type the phrase “voice as an instrument” through predictive text alone); in terms of cultural impact, capturing the Young Thug phenomenon through the lens of a single release may well be futile (akin to flattening a decade in music into a list of albums). This much is clear, though: with each Elton John collaboration or appearance on the set of Uncut Gems, we now celebrate not the actual result thereof, but the absurd, inexorable march of the man behind “Extacy Pill” toward the cultural stature he has long deserved.

The cost, of course, has been paid by the art itself. Hundreds of leaks and a farmers’ almanac worth of Slime Seasons later, the Barter-era Young Thug exists primarily as an echo. His Billboard ubiquity, overdue even if over-corrective, rides on the Burberry coattails of his signees and direct stylistic descendants. His albums, now unambiguously official and uncharacteristically true to their release dates, serve primarily to underline the finer points of their predecessors in the catalog rather than attempting to build upon them.

And yet, there exists one perfectly-preserved document of the era. At first glance, it could be easily misread as a capitulation; features from Boosie and Young Dolph and the endlessly-handwringable dust-up with Lil Wayne were, if not wholly out of place, certainly intentional steps outside of Thug’s Atlanta creative haven. The mere presence of someone in his ear fretting about the distinction between an album and the newly-invented “commercial mixtape” concept did not bode well.

It didn’t matter. Thug’s most vital output has rarely featured (or required) clear, intentional sequencing, yet “Constantly Hating” and “Just Might Be” simply could not exist except at this album’s opening and close. They enclose some 50 minutes of direct exposure to the mind of Jeffery Lamar Williams, a considered exhibition of the entire spectrum of rap performance that can just as easily scan as a stream of consciousness. Four years on, if not from the very moment of release, Barter 6 is a clear coronation: an inflection point between deifying and defining a genre, a record so true to Young Thug’s trademark mercuriality that it’s a wonder it was ever released.

17

Carly Rae Jepsen

E•MO•TION

[Interscope; 2015]

Joy in a bottle: bubbly, sweet, even-keeled, refreshing, perpetually new. I’ve always associated Carly Rae Jepsen with Bruce Springsteen. It’s a tenuous and perhaps confounding association, but the two are nonetheless bound in my mind. It’s in the endless anthems, the blind faith in the hook, the bubblegum uplift, the hardworking hero, the balladeer draped in honest fabric, completely sincere. Most importantly, they both provide an idol to pour oneself into. Carly Rae Jepsen: an adorkable hopeless romantic forever empowered, lost, and doing the most. She’s marked by a public-facing air of humility and stays in her lane with grace. With E•MO•TION, she gave us something to lean on.

E•MO•TION and its consequent reception signify the triumph of poptimism over the past two decades, but, further, it contributed to the divorce of pop aesthetics from strictly mainstream spheres. E•MO•TION was the moment that CRJ stepped down from the super-stardom of “Call Me Maybe” and into a minor-major mid-tier cult-pop status that characterizes the diversified and democratized idol landscape we have today. She helped carve a space for a new format of pop idol, the influencer-artist, a space where musicians can find greater creative freedom via fervent fan support and a creative license to call more shots. Much of the most exciting pop music today is being made in this newly carved space, where artists can take creative risks while performing something like an authentic self just an arm’s reach away from the stans.

Beyond this, E•MO•TION’s acceptance demonstrated a shift in pop criticism, one that moved beyond the condescending, protective defense that poptimism had accumulated. Because its production was lush and organic, because its songwriting was sincere and full of intent, and because its hooks were irresistible, E•MO•TION made it clear that it required no protection. Anthemic without naiveté and strong even when its singer was at her most vulnerable.

This was not pop re-purposed as a tool for critique of Western modes of consumption and production. Nor were arms twisted into taking it seriously tautologically, because it had already proven popular and hence influential. This was pop as a viable music in and of itself. It’s the simple euphoria. It’s in the feeling that arises with the perfect scansion that causes the line “I think I broke up with my boyfriend today/ But I don’t really care” to burst forth in climax. It’s the harmony between her proclivity to constantly ask if she’s “too much” (“Because I want what I want, do you think that I want too much?,” “Oh, did I say too much? I’m so in my head, think I’m out of touch,” or simply, recently, “Is this too much?”) and the fact that she dressed the question in an epicurean, sugary, and burning sonic architecture. Most importantly, Jepsen wasn’t grinning for a moment. She smiled with depth, warmth, vulnerability, and tenderness, but it was never a grin.

“Call Me Maybe” was infectious and viral. It shouted its way through grocery stores aisles jolting shelved goods and brattishly dodging consumers, running amok with love. E•MO•TION’s songs were reeled in, containing the passion but diffusing it, sweetly. They held a listener, talked with them, and left them waiting, wanting more. God bless this timeless crush.

16

The Caretaker

An empty bliss beyond this World

[History Always Favours the Winners; 2011]

Experience, the Tantrics tell us, is fundamentally empty of a coherent self and, at the same time, inherently blissful. It’s in the union that the trick lies — a trick that is an untrick, a seeing of a truth that was always right in front of us but to which we weren’t paying careful attention.

The partially illusory self is a vital concern of The Caretaker’s — zeitgeisty, time-ghosty (or is it the spirit of time itself?) in an age of self-care commodified and endlessly reproduced. The nominal impetus for An empty bliss beyond this World was the experience of Alzheimer’s disease — the mind slowly losing its hold on memory, on those contents that are often seen to constitute selfhood, a tragedy in which all “things” must literally pass.

But among this empty landscape of loss, specificity is not entirely destroyed. Tantrics understand this too, seeing the play of experience as the dance of the God/dess, which both manifests in the particular and is constituted of an underlying non-duality. In an exquisite tension, both perspectives are simultaneously and entirely true. Consciousness-objects persist, karmic or neuropsychological, traces of former actions and reactivities that remain to be set in motion when the appropriate trigger brings them to fruition.

Exquisite and loopy, then — like experience itself. In our dotage, we circle, our emotions are released by reproductions of the art of our prime.

And in the age of mechanical reproduction, there is a nostalgia that can be evoked by the recording as recording, a patina’d sense of “the past” as an idea, not an era. To wit, the crackling, wavering pre-war 78 loops that formed the foundations of Leyland Kirby’s decaying edifice, a hotel full of ghosts. Not so decaying, though, because where pieces like The Disintegration Loops or Kirby’s Everywhere at the end of time series were literally in deconstruction, here the music hovered like gossamer, like ectoplasm produced from the womb of the medium, before being abruptly snuffed out of existence. Each loop was infinitely cherishable, specific in (numerous) time(s) but infinitely extendable, both empty of meaning (if meaning is comprehension, if it is generalizable) and pregnant with innumerable significances.

And then, and then — a decade after its release, An empty bliss is now a historical artefact itself, subject to the fate on which it is also commentary. It’s a punishment that fits the crime (can’t cheat karma), evoking an infinite regress of nostalgias.

The angel of history sees catastrophe — the angel of memory, bliss. The function of the angel is to act as the Singing Detective, but when the time between the stimulus and the consciousness of the stimulus extends to encompass all of infinity — as any moment of time does — how can we ever ascertain whodunnit?

15

Grouper

Ruins

[Kranky; 2014]

After years of wading through the mire of dystopian visions, uncertain futures, and supposedly imminent ends, Ruins was what it felt like to look back. It was a loose morsel of time captured through memory’s haze, eroded through absence and polished through rumination. It had a tangible presence, an organic universe built into its corporeal sounds, but in its soul, it was still a soft mystery. It was isolated and hermetic, honest about our era’s spirit of solitude and solemnity without being broken down, a passage between 21st-century dreams and the waking world beyond. It was, in a sense, just Liz Harris, her piano, and their frail partnership, but in every crack of silence and every sustained chord were sylvan echoes of a neverending tempest roiling outside. She envisioned herself, quiet and remote, cloistered against an apocalyptic storm, reflecting on lived histories and traditions through tender piano serenades. Before we were lifted into the architecture of a new age, Grouper transported us down to the ruins below. Someday we might return.

But what did we find percolating out of the rain-sodden soil? Faded lullabies about remembering what it is to laugh and love and fall apart as we turned numb in the gale. Spectral sense memories of lovelorn anguish (“Call Across Rooms”) and loneliness (“Clearing”), as well as — through some magic — remnants of a corroded hope (“Lighthouse”). Ruins had an arc of transformation, from material (“Made of Metal”) to ethereal (“Made of Air”), present to past, which was expressed in a sonic chart of ephemeral details — a croak, a creak, a rumble of thunder, a beep — that evaporated into glistening, imperfect reverberations of liberated sensations. Breaths became emotions, as in the lilting, whispered harmonies of “Holding” and the repetitive angst of “Labyrinth,” and then returned to vapor. We’re still turning circles.

Ruins survived beyond those tremors, though. Preempting the skeletal static of Grid of Points and the celestial miasma of After its own death / Walking in a spiral towards the house (as Nivhek), and unfurling from the full resonant body of The Man Who Died in His Boat, Ruins was Harris distilled but complete, balanced in meditation under solitary candlelight. It’s that minuscule aura of warmth and that light of guidance that will comfort us in the moors ahead. When nowhere felt quite like home, Ruins was a familiar enough wilderness.

14

Arca

&&&&&

[Hippos in Tanks; 2013]

We craved a way to say we’d changed. We sought an art to measure ourselves. We traced each others’ whole silhouettes against butcher’s paper and held the outlines up to light. Where the limbs jutted so, where the brow distended out, the neck, the nape, the ass, these whole sacs of we filled with nothing; how had we shifted? And had it been natural or somehow induced by a foreign agent? And had we meant to change? And how even were we when we’d started this stretch of 10 years, this arbitrary meaning marker? And how were these renditions — these places where pens had swerved, blobbing edges and adding nodules — how were these ruins of self-portrait different from how we actually were? And what if what we made was actually us, what if it were up to us? And and and and and!

She whispered, she shushed. It sounded like clicks and peals, but we recognized its meaning; any apprehension gave way as we distended, unknotted, reclined into an embrace. The first time you feel at peace for want of a lover’s limbs. The inching desire to be covered up by another, to uncover in the heat and glow and melt into, through, under? To recombine in grime, to find the holy and profane in clicks and peals — this was the gnashing brightness of &&&&&. This was where we first started to unrecognize.

We were cognizant of Arca before &&&&&. Her production stretched into monstrous dwellings, sutured the devout and hateful corridors of Yeezus, milked raw a well of want on FKA twigs’s EP2, would later marry into Björk’s elegy out of bondage. But &&&&& was sheer incandescence bellowing out and between the teeth of the future’s nerviest composer, a place where dub and hip-hop and piano concerto lost shape against each other. It was the shape of a new being shaking; we were shaped into newness by it, and it demanded nothing less than total transmutation.

Transmutation, as differentiated from the sometimes imperceptibly horizontal gene moves of transformation, is a complete change in appearance, structure, and metabolism. In &&&&&, lost sounds (whipping, a moan, guttural animal) were not recognized but re-rendered against a flanged history of musics. It was the evolutionary entry into a decade-long transmutation, shocking a swallowing whirl of flange deep in the belly (Xen) through the enmeshing of digital bodies into new being (Mutant), past the absorption and purgation of hate-bred traumas (Entrañas) into a pure peeling evolution of voice beyond the human (Arca). More than any other experimental maker this decade, Arca’s sounds were designed to be experienced as they were sounded (alongside each other unbroken — an arts of mixtapes!) and as paeans to an evermutatation. Change catalyzed in the moment of encounter. Reflection taken after occurrence was already watered down. As tempting as it was to trace and track and wonder through our history, we were prompted — those clicks and peals! — to be in and then move through. Her voice, unrecognizing, a fluent fluid full of swerve and love. And and and and and!

13

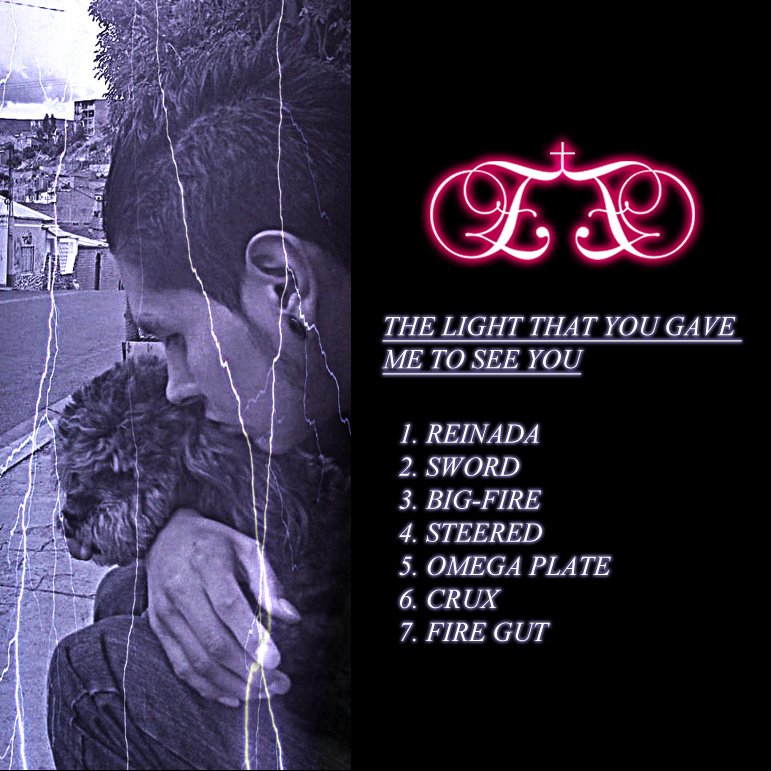

E+E

THE LIGHT THAT YOU GAVE ME TO SEE YOU

[Self-Released; 2013]

Interpretation is an attempt to bring one’s preconceptions into play so that the meaning of a work can be made to speak for us. Our historically-effected consciousness defines a horizon, a culture, and a tradition that inform how we understand a text, art. I can’t separate my experience as a migrant and my Bolivian origin, two features I share with E+E, from my interpretation of THE LIGHT THAT YOU GAVE ME TO SEE YOU. Instead of chaos, worldbuilding cut-ups, or a sound collage for the digital era, in her music I hear the buses and pedestrians running around the streets of La Paz, I hear the markets in the border between big cities and indigenous areas, I hear Quechua youths dancing in abandoned warehouses. The way E+E picks and connects ideas, references and temporalities, sometimes with violence other times with great tenderness, is a method of knowing common to many migrants. We make sense of daily life by appropriating, preserving, remembering and discarding from the streams that lead our journeys. Thus, Lil Jon and huayño are no more contradictory than any other of the strands that compose our identities, at once ancient and futuristic, autochthonous and cosmopolite, deterministic and polysemic.

The heterotopia emerged from such process would sound, one imagines, similar to “Fire Gut,” “Steered,” “Crux,” or “Reinada,” tracks off THE LIGHT THAT YOU GAVE ME TO SEE YOU. That is, juxtapositions of spaces, times, forms, and styles, where Bonnie Raitt, saya, crunk, and plunderphonics not only coexist but make sense together. The thought experiment of the Martian Museum of Terrestrial Art could be enlightening to consider here. How would an alien archeologist interpret the history of (human) art, to then organize it as an exhibition? Most of the links they would propose are unthinkable to us, for they occur outside a recognizable sense of history. Free from normative frameworks, the alien would come up with essentially original groupings, emanated from a compressed and pure present.

In her work as E+E, Elysia Crampton heightens that strangeness, perhaps because she has been made aware of such character through her experiences. A topological examination of her work could describe her compositions as abstract spaces where information and objects appear, then undergo multiple and instantaneous transformations. If looked properly, that is also a description that applies to lots of other instances of the human experience. Being new to a collective or language, an alien, may bring that facet to the front; hence, putting migrants in an ideal position to examine those tensions. Not that this could be sufficient to explain the work of artists like Chino Amobi, ANGEL-HO, or Lotic, but perhaps it may catalyze the consistencies and similarities between their art and E+E’s. Thus, allow for a positivist reading, as I claim that blood-splattering effects, robot sounds, Afrobolivian drums, and the rejigging of R&B hits might be an emanation powerful enough to conjure the allure of an imperial-capitalist world in its degenerative splendor.

With all this, I tried to argue for the importance and value of THE LIGHT THAT YOU GAVE ME TO SEE YOU as a meaningful artifact of the last decade’s culture. Is it disingenuous to impose a retrospective narrative on music that defines itself in opposition to grand narratives? What can one make of the contradiction between the permanence of recorded music and the ephemeral connections to which E+E aspires? She seems preoccupied by that herself, seeing how hard she has worked to scrub her own tracks. Very little of her art is available online. Even less information on her and her activities. It is just natural for one who has made contingent reconfigurations a way of living. That which is very meaningful to her is simply random for others; a switch in that valence is feasible but not that both could stand on identical grounds. Interpretation can only be a rich melding of artifice and performance on that condition. That will likely make of this list and comment mementos of a ghostly expedition. Perhaps lost to oblivion. Certainly, open to alien reconfigurations and appropriation.

12

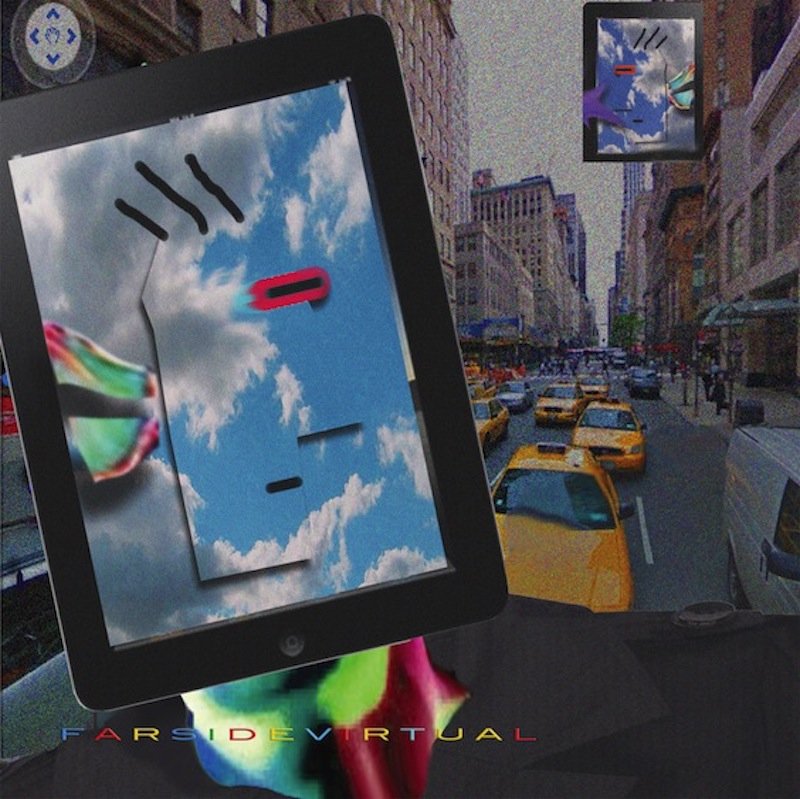

James Ferraro

Far Side Virtual

[Hippos in Tanks; 2011]

EVERY SINGLE THING this decade was augmented and pushed to the extreme — and we bought it up. From absurd viral pop music to vanilla latte-flavored Pop Tarts, so much of the last 10 years felt captivatingly ridiculous, fake, over-the-top — so plastic. And we were saturated in it, embodying it, vomiting it. Sometimes literally: While the petrochemical industry nourished our landfills and choked our rivers, we were inhaling microplastics and eating plastic debris.

James Ferraro, our Last American Hero, explored this nightmare of excess and its ecological consequences early in the decade with Far Side Virtual. Rather than spewing diatribes about our current condition or signifying discontent through his then typical maelstrom of noisy experimentation and lo-fi hijinks, Ferraro captured the irrationality of consumption by becoming the nightmare itself. Far Side Virtual wasn’t about plastic; it was plastic. So why listen to it?

This disconnect between listening to stylized music “about” what we despise vs. listening to music that became what we despise found expression in various (and vaporous) ways this decade, but it was Far Side Virtual that united accelerationism, hyperreality, and a cheeky approach to High Art Aesthetics™ in such an unusual, confounding way that you could simultaneously embrace its kitschy simulacra and feel repulsed by its visceral fakeness. On the surface — which is where, despite our best efforts, we all tend to reside — its elevator beats, infomercial horns, and corporate chirping played like a “rubbery, plastic symphony” for avatars interacting and transacting in the virtual worlds of Second Life, like a “PIXAR meme” for digital natives raised on the global ambitions of Google and Bitcoin. But these URL-based evocations were met equally with IRL-based implications, sounding in this latter context like a soundtrack to the plastic trash swimming in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, to the dead bodies emitting “incongrously cheerful” ringtones from their technological appendages.

Far Side Virtual felt like a comedy, but it wasn’t funny. Instead, the album offered a sound so lively it felt lifeless, so synthetic it felt alarmingly real, so nauseatingly jubilant and terrifyingly pristine that its vulgar caricature of societal structures largely overshadowed its complex musical ones. Far Side Virtual was described by Ferraro as “still life” — that is, a frozen depiction of 21st-century society — but perhaps the most depressing part is that this “still life” is also still the life we live. It was horrifying, overwhelming, oppressive. But we consumed it, because that’s what we do best. We consume. And then we consume more. And then we consume more. And then we consume more. And then we consume more. And then we consume more. And then we consume more. And then we consume more. And then we consume more.

But don’t worry. I hear it’s rebellious these days.

11

Babyfather

BBF Hosted by DJ Escrow

[Hyperdub; 2016]

Regardless of how you might feel about the current state of intercultural dialogue and mutual respect in the world, there is no question that we urgently require more unity. We need unity, not just in our neighborhoods, our broader communities, and our districts, not just across our nations or even our continents; we need unity as a species. This is arguably more imperative now than it ever has been in the past; we are connected before we are even born, plugged into a network before we even learn how to walk; we need to be able to navigate it in the same way and with the same level of dexterity of our day-to-day life in the physical world. But at a time when unity has never felt so necessary, it has also never been so fractured and distant.

BBF was the soundtrack to a transition, to a moment in the history of humankind that witnessed a shift in the way that we relate to people around us and away from us, people we have never met and people who we know intimately, people who we care about and people who will never know us by anything other than an internet pseudonym. But these tracks did more than document that transition. They channeled the before and the after, the corrupted relations that exist between postcodes and the potential unity that exists across continents, all on a radio station broadcast in London — a melting pot of vibrant multicultures, community engagement, hate-riddled phobia, and indiscriminate violence. Where is that unity, and what does it look like? Where is the pride that we should all feel, not about being from a place, but about instinctively respecting each other, regardless of who we might be or where we might be from?

BBF was assembled so fervently and so accurately that it captured a fracture across both the entire planet and the entire mind of an individual reflecting on how they fit into it all. The album was painstakingly curated by an artist so desperately in touch with the multidimensional realities around him that it also served as a prediction, at once filled with both a giddying sense of optimism and a desperately bleak amplification of despair.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series