We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

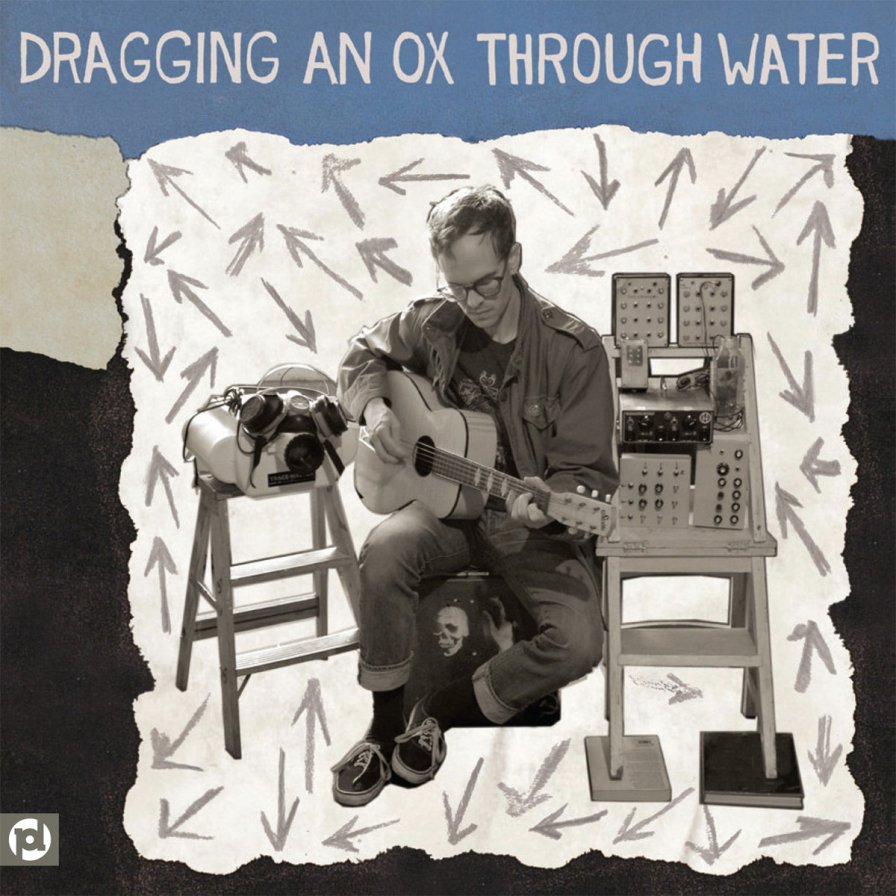

Dragging An Ox Through Water

Panic Sentry

[Mississippi/Eggy; 2014]

With his lonesome, steady voice and idioelectric gizmos, Brian Mumford’s Dragging an Ox Through Water sculptured something of an eremite image. Alone only to tinker with chords and give expression to mercurial current, each of Panic Sentry’s songs felt like a rare visitation from the hermitage and a uniquely affecting document of simple, direct potency. These were delicate songs, as friable as the man and machines that made them. Squealing, swelling, burbling issuances from obstinate, jury-rigged electronics cradled and disrupted his low mumbled melancholia, his feral nature, his thirst for war. “I am turning into scum,” he crooned, as a violin grinded away behind him. Postures assumed with intelligent self-deprecation indulged in hopelessness and disintegrated under their own reflection. He was a wolf in disguise. He was a witch in the lowlands. He was ally to the rats and the weeds. Every element of these recordings converged toward this sense of being at the margins in a place pregnant, powerful, and wholly apart. There was beautiful, difficult life in the evil forest.

E+E

☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆

[Self-Released; 2013]

☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆ comprised some of the most delicate and refined works of Elysia Crampton. Back in the days of her E+E moniker, Crampton drew new boundaries for electronic music with her precise fusion of huayno, Afro-Bolivian saya, and cumbia. On ☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆, she laced vibrant rhythms and flagrant pulses of Latin America with foreboding ambient and choral music, which drifted and indented the impeccable tracklist that made this one of the most important releases of Crampton’s catalog. Even though ☆ Original Works ☆ ♫ ☆ is near impossible to find — it was originally a SoundCloud playlist, with several of its tracks off Bound Adam — and indeed does not exist as an official release, it remains an impeccable piece of work and a testament to the creativity of one of this decade’s finest.

Future City Love Stories

Future City Love Stories

[BLCR Laboratories; 2017]

You and I have met before. Remember? We moved into an underground skyscraper, where Future City Love Stories rained down from the soul of the sprawl. They carried ambient lamentations and autobiographical elegies from the crowded interior, swept into the deepest and lowest gutters: graffiti-stained tunnels, gacha alleyways, arteries of black machine static. They throbbed in cosmopolitan aggregate: traffic vibrations, the heavy trickle of greasy rain, notes from an upscale hotel, advertising lingo in another language. Whose voices were they, again? I can faintly remember… They change in mood but not circumstances, almost like us. We used to talk different, feel different. Remember? But that light will never break again. Not down here.

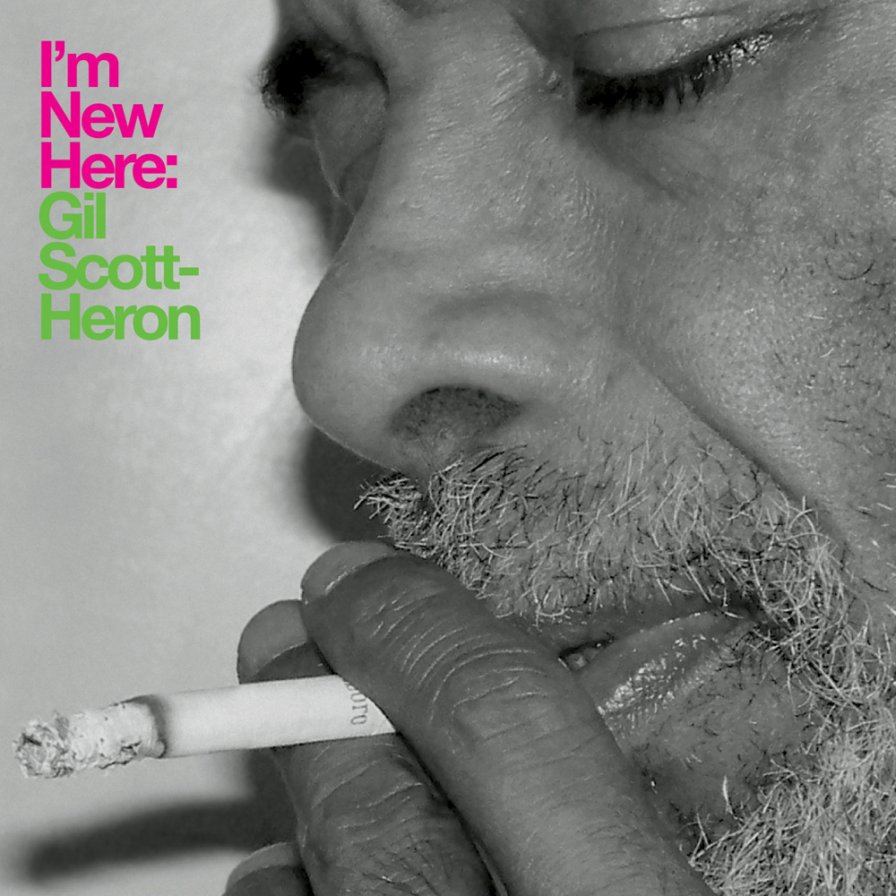

Gil Scott-Heron

I’m New Here

[XL; 2010]

After a legendary run of 13 albums in 13 years, from 1970-82, Gil Scott-Heron largely disappeared from public view. In the 2000s, he was in and out of prison on drug charges, in danger of letting his legacy slip away from him. To those in the know, Scott-Heron was the godfather of rap, but to many in the younger generation, he was remembered, if at all, solely for the 1970 track “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” By 2008, though, Scott-Heron was out on parole and planning his comeback. I’m New Here was a short album that borrowed its title track from Bill Callahan and featured just as many spoken-word pieces as proper tunes. Against all odds, it worked. The album sparked a Scott-Heron revival, helped along by Jamie xx’s remix album We’re New Here. Scott-Heron’s tired, smoky rasp was way up in the mix, his humor and his pain on full display, his sensibility hyper-modern, his musical chops sharp as ever. Scott-Heron died a little over a year after the album’s release, but he had achieved the nearly impossible act of crafting a comeback album that redefined his legacy. For some listeners, he was new here; for others, it was a pleasure to welcome him back.

Holly Herndon

Platform

[4AD/RVNG Intl.; 2015]

“It’s levels to this shit.” I can only assume that when Meek Mill said this, he was talking about Holly Herndon’s multifarious and prismatic “NSA breakup album,” Platform. There was a lot of lot-ness in it; there’s no pretending that it wasn’t dense, heady, and even a bit pretentious. Platform made IDM’s goofy acronym seem a little less ridiculous; if there were such a thing as “intelligent dance music,” this was it. What it wasn’t, however, was unaware of its aims and its affect, of its theoreticality and its materiality. Making distinctions between “club” and “academy” though is a tired and boring starting point for dissecting this kind of shit; Herndon’s reality is that she’s got one foot in both spaces, and Platform’s most visceral sonic tensions stemmed from this, in striking and bodacious ways. Hearing Herndon justify her project in her own voice was fascinating, but what was so special about Platform was that, despite its staggering profundity, it spoke for itself; like a Tolkien novel, its sheer awesomeness was only strengthened by its conceptual depth. There was still snippets of brilliance and power I’m finding in it, even as I dance to “Chorus” in my broken desk chair. So yeah, Meek, I agree: It’s levels to this shit, and Platform still succeeds on every one.

Ital Tek

Bodied

[Planet Mu; 2018]

A trend in the 2010s was an increasing tendency for electronic musicians to try their hand in scoring for film and video games. Ital Tek, having just written the soundtrack for video game Laser League, named his following album Bodied after a gaming term for death. Ital Tek’s dark dubstep roots continued to grow fainter as he explored the emotional depths of bass music, delving deeper into what he had established with the equally transcendent Hollowed in 2016. Relying less on thudding beats and leaning more toward melancholic, atmospheric excursions led to a record that was by far one of his most visual. Developing a language of skittering percussion and growling, arpeggiated bass lines kept the entire album injected with a dazzling, grandiose flavor that only grew more epic as it progressed.

Jim O’Rourke

Simple Songs

[Drag City; 2015]

Jim O’Rourke’s Simple Songs, popularly referred to as his third “singer-songwriter” album, was released almost 14 years after Insignificance. And it was just as brilliant: In a parallel universe, tracks like “End of the Road,” “Half Life Crisis,” and “Last Year” would be hit singles pored over and dissected by historians for their unique contributions to modern society and popular culture. But while Simple Songs was just as overwhelmingly creative and diabolically clever as its predecessor, it also found O’Rourke in a more subjective, winsome mood. He was still funny as hell — proving himself to be the king of one-liners and the greatest out-of-work comedian of the last three decades — but his lyrics here were more relatable and inflected with sadness. These simple songs were simply captivating. O’Rourke, working once again with high-caliber musicians and master masterer John Golden, delivered an album more than worth the nearly decade and a half it took to see the light of day. Here’s hoping he’s hard at work on number four.

Kyary Pamyu Pamyu

なんだこれくしょん (Nanda Collection)

[Unborde; 2013]

I’ve read a lot of colorful, inflated stories about the Harajuku district, an epicenter in Japan for street fashion and youth culture. Then I visited, and while the streets did indeed boast wild outfits and concentrated pockets of fantasia, it felt tame compared to the hyperbolic descriptions of it. (Didn’t help that American Eagle was just down the street.) But while it’s easy to sell a simulacrum of Japanese culture through the frame of Western fetishism, it’s difficult to overstate the sensory overload and colorful aesthetics exploding from Nanda Collection. Even six years since its release, Nanda Collection — which translates, appropriately, to “What’s this collection?” — pushed further than many of today’s most experimental pop, finding itself drenched in highly-stylized productions that matched the outrageous exuberance and infantilized provocations of Harajuku Princess and fashion monster Kyary Pamyu Pamyu. Erupting with powerpuff melodies, sprightly syncopations, and a playful, almost cartoonish approach to genre, the album had the capacity to both overwhelm our senses and effectuate desire, every second of it brilliantly and obsessively embellished by mastermind producer Yasutaka Nakata. Nanda Collection was truly one of this decade’s great pop experiments, J-pop or otherwise, one that helped spark the internal conditions for pop’s own violent rupture, which we are still seeing play out today in all its grotesque, carnivalesque glory.

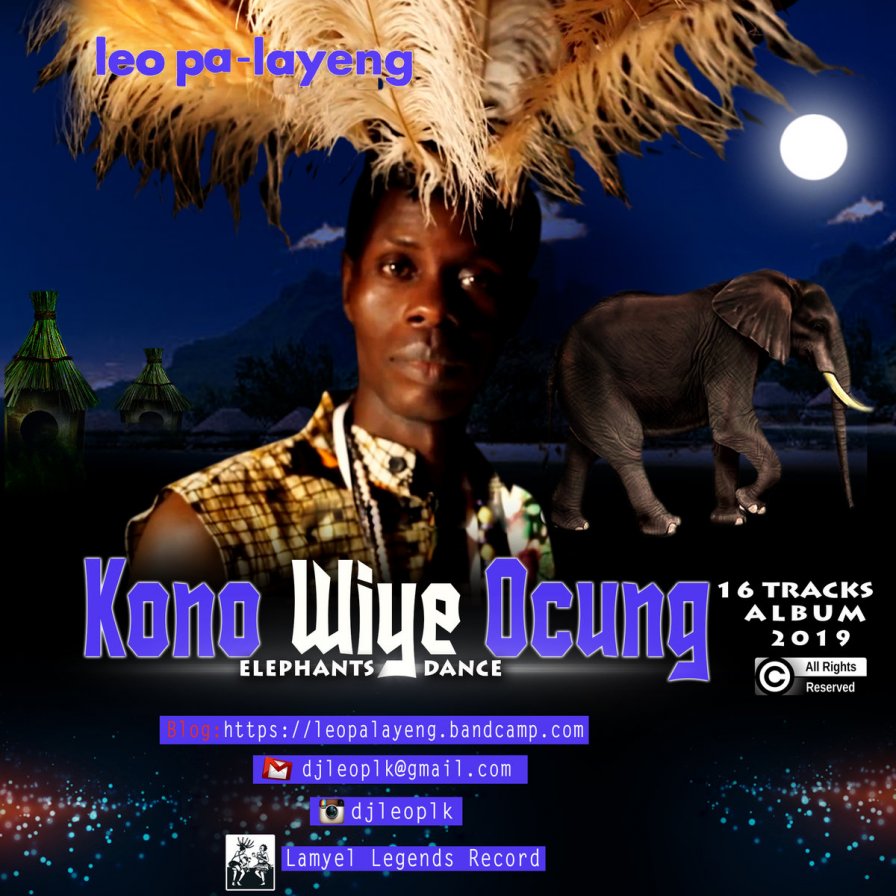

Leo PaLayeng

KONO WIYE OCUNG

[Lamyel Legends; 2019]

KONO WIYE OCUNG was unbridled excess: of tempo, of timbre, of sheer radiant joy. This was the electro Acholi kaboom, albeit one that seemed to completely outrun our critical apparatus altogether upon release (with regard to its relatively low profile in the nebulous world of Online). An altruistic narrative spirit pervaded here, as Leo PaLayeng Kenna weaved traditional folk musics, instruments, stories, and characters with electronic embellishments that provided a generous update on its highly localized source material. In fact, there was no need to compromise on the histories that coalesced here — the best testament to that fact came on “AWIDI LEGACY,” wherein Leo PaLayeng invited us to celebrate an Acholi princess whose dance “attracted many fragmented tribes,” an embodied “Super Cultural diversified, in the sunshine land of Africa.” That was precisely KONO WIYE OCUNG’s M.O., an album that pressed on with such a fundamental openness, grounded in its particularity, that it enjoined its listeners in irresistible communality and material release.

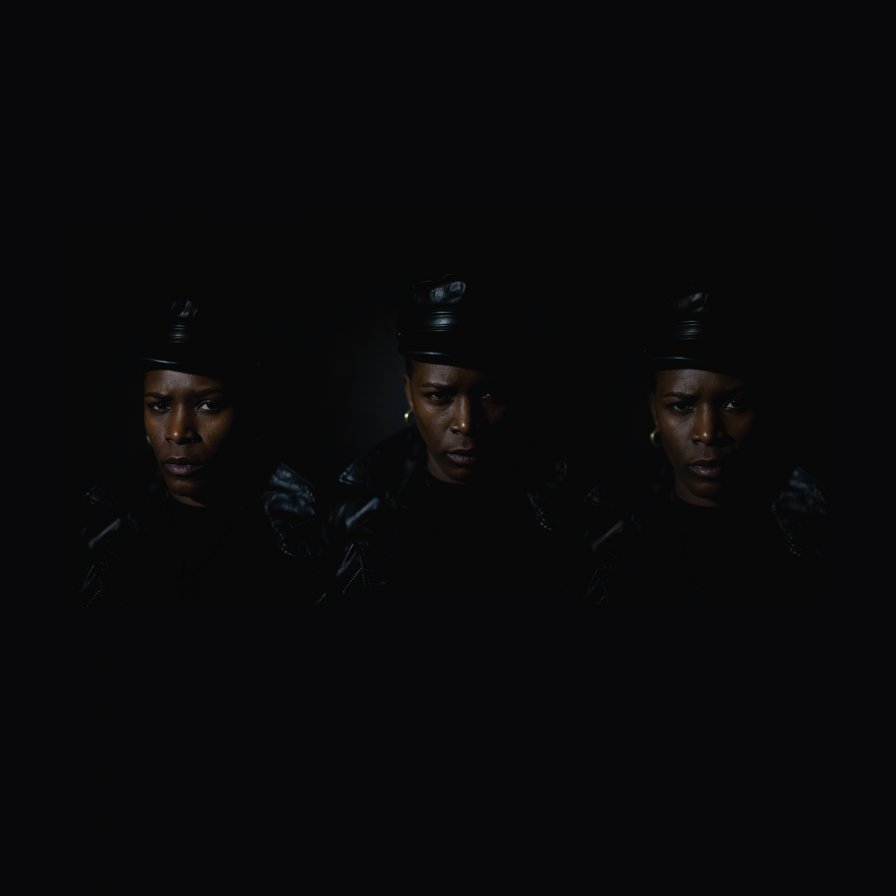

Light Asylum

Light Asylum

[Mexican Summer; 2012]

Before everyone started re-evaluating 1990s nu metal (which, all yuks/nostalgia aside, never got any more palatable than Faith No More), Shannon Funchess and Bruno Coviello were putting their heads together to breathe new life into the sounds of the previous decade, of which many of the less-heralded innovators have gradually reclaimed from its interminable, toothless wash of MOR security blanket nostalgia. Like the best darkwave acts of the 1980s, Light Asylum took the pleasing overtones of new wave and artfully blended it with unadulterated ferocity and anguish. Despite the gorgeous single “A Certain Person” having been slung on the end of this debut, song-to-song the listener was helplessly drawn in, making that 2010 highlight feel like an old equine friend once arrived at. The most confounding aspect of this group’s subsequent dissolution is how unstoppable Funchess proved herself at writing vocal hooks (perfectly complemented by her and Coviello’s muscular, richly accented instrumental arrangements). These songs embodied a tight, sing-along-inspiring quality that obliterated any reservations about lyrics (definitely on the hokey side at times). Her baritone vibrato was a thing of rare command and, for a moment, a distinctive voice in a genre that could still use one.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series