We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series

The Babies

Our House On the Hill

[Woodsist; 2012]

Oh Lord, have mercy on my soul, as it crumbles into the wind and stains the whole sky a shade of barbecue gone bad. Have mercy on my demon ass, jittering until I bruise, like a shattered animal with a shit heart. I know I said that every day makes me want to howl, but I learned to throw my face toward heaven and cackle while wandering into the void. Remember when I screamed that I would fling my corpse off this fucking mountain. What I meant was that I craved the sun bleeding onto my face and that I would jump into my car and drift toward the desert as soon as I chopped my hair like I have always been threatening. Promise me three things before you scuttle off the edge, promise that you will do my hair like you do it, promise that you will shake your hips, and promise that you will pour one out for the goddamn Babies.

The Brave Little Abacus

Just Got Back From the Discomfort—We’re Alright

[Self-Released; 2010]

You know that feeling when your heart is this close to breaking and you’re about to explode from cranial pressure and your eyes well up but you can’t find the words so your face strains and puffs out like a sea urchin and you really really want to explore different modes of being outside a human body but there’s no accounting for corporeality so you just have to deal with it because hey so is everyone else might as well connect through dread? You know that feeling, right? Just Got Back From the Discomfort—We’re Alright is that feeling: straight, undistilled, without restraint.

The Lonely Island

Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping

[Republic; 2016]

Shame on all of us for making this film a box office bomb. Popstar: Never Stop Never Stopping is the best music documentary since This is Spinal Tap and perhaps the premier pure comedy of the 2010s. In terms of laughs per minute, it’s off the charts. “Wait a minute,” you, a heathen who has never seen this movie, ask impatiently, “isn’t this a list about music releases?” Guess what, hotshot? The soundtrack for Popstar was legit, positively ripe with hilarious parodies of pop music clichés that were also catchy as all get out. “I’m So Humble” beat Kendrick to the punch by a year, and no one ever talks about it. “Incredible Thoughts” dared to ask deep questions, like “What if a garbage man was actually smart?” And here was a stone cold fact: the hardest I laughed this entire decade was when I heard Andy Samberg as Connor4Real sing, “Knew she was a freak when she started talking/ She said, ‘Fuck me like we fucked Bin Laden’” for the first time. “Finest Girl,” a perfect song. Truly — and unlike the Mona Lisa — Popstar was far from an overrated piece of shit.

Tim Presley

The Wink

[Drag City; 2016]

The Wink was a breakup album for frantic romantics — bitterness and tears were mixed with hot colors and flung at the canvas or cut up into Syd Barrett word collages in a pacy state of regret, arousal and disbelief, “in an ostrich elevator and a book with dog-ears.” Producer Cate Le Bon stripped Tim Presley’s White Fence down to the gnarled wood and helped reassemble it into spiky abstract sculptures dusted with real rock flavor. Presley’s citrusy guitar scraped against old-time dance hall piano arpeggios, as his ecstatic recall of how “love was in his eyes” disintegrated into a sigh of “I know what you are…” The album’s showstopper was the gorgeous, purple-bruise ballad “Morris,” where Presley finally sat down with a cocktail or several and cut loose on his qualifier. “You could be excellent… if you don’t know,” he crooned, before narrowing his eyes: “Make the most of it / When you tell me that I’m ugly / Don’t ever put me on the moon again.”

TREE

Sunday School

[Gutter City Ent.; 2012]

In fall 2012, I penned my first feature for Tiny Mix Tapes, a would-be year-end essay Mr P rejected so kindly that I thought he’d accepted it. He published and paid me for it anyway; that’s how nice P is. On Sunday School — one of three subjects of that essay — TREE presented an ideation for hip-hop so unique, prescient, and polarizing that the genre’s biggest stars spent the rest of the decade struggling to reiterate it. That’s how nice TREE is. Yet, for all its genius — mining nuggets of golden-age gospel from pre-trap gang culture, syncopating beats and rhymes in ways rarely heard hitherto or since, taking rap music in an organically fruitful direction, etc. — Sunday School’s appeal was never academic. I got into it because I could play it over and over and over while heading to the beach, lying in the sand, and coming home. Technically, it’s not even a summer mixtape, having dropped in March, but I still find myself returning to it around that time of year, every year. With each one that passes by, I catch things I’d missed on previous listens, while radio rap creeps closer and closer to approximating its sound. If part of “aging well” is making more sense in light of what’s come to pass, Sunday School might have done the impossible in somehow actually getting younger. It’s miraculous. It’s… TREE!

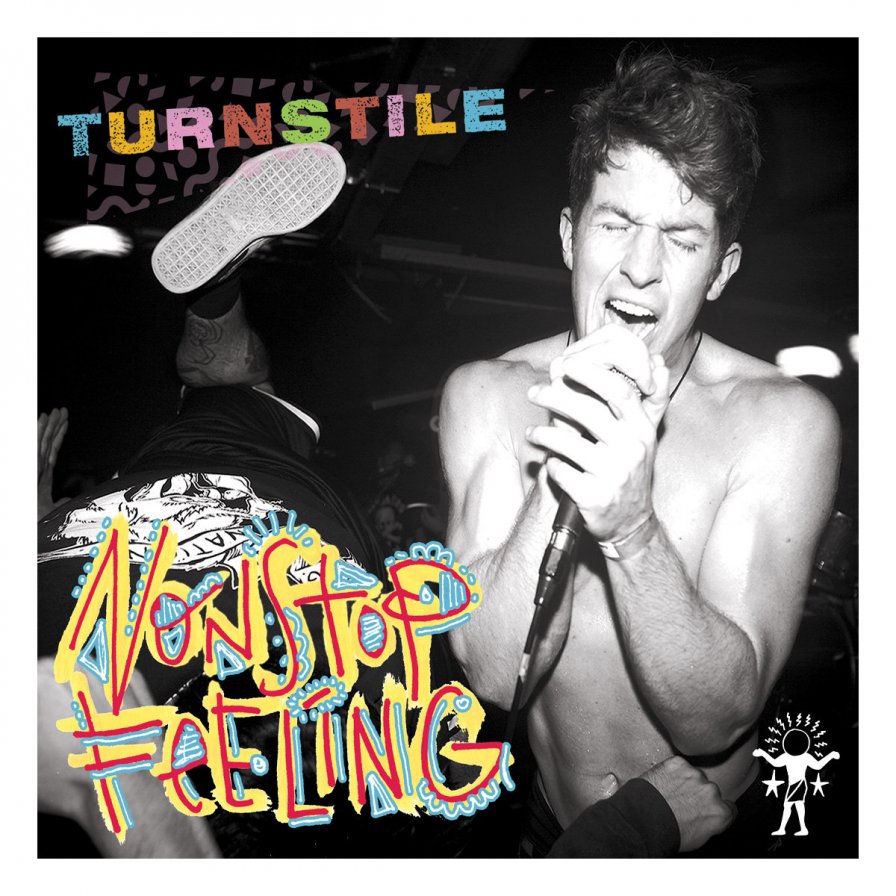

Turnstile

Nonstop Feeling

[Reaper; 2015]

A debut album can be a tantalizing promise and its simultaneous fulfillment. That’s doubly true in a volatile genre like hardcore, where bands frequently make one record and pop like balloons. Turnstile didn’t do this. They went on to sew their jumble of ideas into a more coherent sound instead, but their first album remains captivating for its ramshackle hotrodding of a bunch of shit together — they reminded you Rage Against the Machine was a kind of punk band; they put simple, pretty backup vocals behind Brendan Yates’s yelling throughout; they put a pit shot on the cover but topped it with multi-color scribble. The beauty of Nonstop Feeling was its lack of integration, its splatter of genre signifiers. I won’t say Turnstile started this decade’s trend of hardcore bands reclaiming parts of the 90s’s most maligned jock-rock subgenres, but they will be looked upon as emblems for it. The closeness to rap-rock made them a conversation piece, but moments of contradictory softness made the album three-dimensional: The surging power-pop of “Blue By You,” the contemplative, almost-surfy “Love Lasso.”

TYPHONIAN HIGHLIFE

H.R. GIGER’S STUDIOLO

[PACIFIC CITY SOUND VISIONS; 2014]

Sometimes there is no reason to describe such deep sensations, because the reflection will never do justice to the feelings. But the feelings put positivity and pressure on a need to gesture and to explore and to revel, because the magic within the sounds create too much connection. Heavy-set tubes from one brain plug into the brains of others, connecting them with joy and puzzlement and distillation, showing you a new way and keeping you completely informed. Never before has this experience been so real, because it props you up and stands you on a cliff edge overlooking your own body; you can take that journey because you have been given permission.

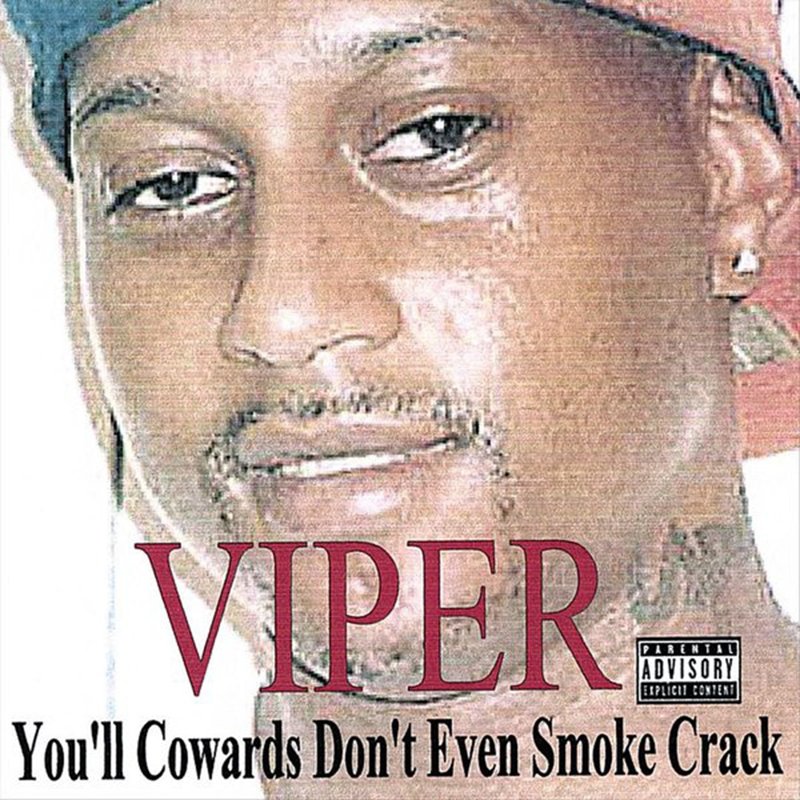

Viper

You’ll Cowards Don’t Even Smoke Crack

[Rhyme Time; 2008]

Two icons to frame this decade’s rap hustle: Viper and Kanye. Superficial distinctions aside, their careers followed mirroring paths. From man to myth to meme, from pop culture figure beyond good & evil to derided reprobate to, ultimately, an inscrutable creative force whose divisiveness couldn’t negate their cultural cache.

To be sure, while in the 2010s Kanye was in his second decade as a music industry luminary, Viper emerged from the entrails of the internet as much as a curio as an artistic visionary. Whereas avoiding every detail in Kanye’s life was often impossible, most people probably first encountered Viper as a viral sensation. In late 2013, “You’ll Cowards Don’t Even Smoke Crack” started to pop up in YouTube feeds, boards, and social media. From the title onward, the track had the discomforting rawness of outsider art, though it was not exactly that. It was old but not the latest Japanese synth-pop rarity spat-out by an algorithm. It was meme-worthy, but also the work of a serious artist. It was not too far from what Yung Lean, $uicideboy$, BONES, or many other SoundCloud rappers were releasing then; hence, half a decade ahead of its time. It was just tacky and unselfconscious enough to generate interest. It sounded good, and there was a lot more where it came from. And considering the hundreds of albums Viper has released since, that’s quite an understatement.

Then, what let You’ll Cowards Don’t Even Smoke Crack, a five-year-old record, capture the zeitgeist? Vaporwave, hypnagogic pop, the impish humor of Hype Williams, Lil B, and the meme rap scene provided the context for a weirdo who milked the presets of his cheap gear like a master, married chill beats with a mumbled flow, and boasted about the most ludicrous stuff while doped out of his mind to be right at the peak of the wave, even if for just an instant. With bangers like “Parlayin’,” “Merciless,” and the title track, Viper can claim to have made a dent in (online) pop culture in the 2010s. Influential? Transcendent? Who’s to say. As the decade nears its end, Kanye and Viper continue to be reliable sources of outrage and fascination. Perhaps their careers finally diverged on a hospital bed, where Kanye landed after a prolonged mental breakdown and Viper because of the pneumonia he developed from trying to shrink his torso using a harness. Upon recovering, Kanye remerged a Christian. Viper, to further complicate his already problematic relationship with fans, emerged to crowdsource content and try to force himself into meme-relevancy by claiming responsibility for 9/11 and Epstein’s demise. Such is the burden of genius.

Waak Waak Djungi

Waak Waak ga Min Min

[Efficient Space; 2018]

A pall of smog falls across the window of the air-conditioned office building from which I write, obscuring buildings no more than a few meters away. Despite the chilly air inside, I can still smell the smoke. In Australia, cities are choking while the country burns. In my country, our rainforest is going up in flames and our precious water is siphoned off by the megalitre to rapacious corporations. As an Aboriginal man, I’ve wondered whether we might respectfully borrow from Afrofuturist imaginings to understand what is happening — to seek ways to represent the intermingling of nature and technology under colonialism, and to sing of despair, but also of hope, of unfolding possibilities and the ways we can reclaim our stolen land both in art and in actuality.

In doing so, Waak Waak ga Min Min has been a touchstone — imagine, fingers brushing the smooth warm surface of a pebble pregnant like an egg with history and the promise of renewal, even if only in an (eternal) moment. Waak Waak Djungi are songmen from Yolngu country, far from my home, but their rough-edged, spiraling chants, interspersed with electronics and field recordings, speak to me deeply. But, for me at least, this is a “personal” engagement, where nonetheless, as a listener, one does not take in to the self, cultural appropriation-style. Instead, the self realizes its own littleness in its connection with landscape, history, and futurity, both recognizing otherness and how it refracts through one’s own circumstance, able to relax completely in the knowledge of being held without having to let go of either the fear of annihilation or the seed of resistance.

WU LYF

Go Tell Fire to the Mountain

[LYF; 2011]

WU LYF was a difficult band to talk about. Pronouncing their name out loud sounded like “Woo! Life!” which didn’t hold quite the same weight as World Unite Lucifer Youth Foundation. And their sound was equally difficult to elucidate — Ellery Roberts’s distinct lead mumbles were like a drunken Tom Waits slurring his words and trading swigs with an over-smoked Samuel Herring. Their guitar and drums crashed and hummed like an Explosions in the Sky track operating within traditional song structures. The band self-labeled their sound as “heavy pop,” which was a buzzy genre tag, but it didn’t actually mean anything. The fairest description might be that they played a sort of gospel music for a post-apocalyptic world, equal parts hope and cynicism. Besides a farewell song and a few remixes, Go Tell Fire to the Mountain was the entirety of the band’s output. Their sincerity and authenticity were eventually questioned, but that didn’t matter to me. My connection was real enough that I tattooed the WU LYF cross down my arm to memorialize a time of emotional upheaval in my life. Of course, WU LYF was also an acronym for World Unite Love You Forever, so maybe it was a celebration after all. Woo life, forever.

We are celebrating the end of the decade through lists, essays, and mixes. Join us as we explore the music that helped define the decade for us. More from this series