Megan Mitchell creates atmospheric, sonically dense electronic compositions under the Cruel Diagonals moniker. Her debut album, Disambiguation, arrived last year on Drawing Room Records, with companion cassette Pulse of Indignation released digitally this past January (after having been available only on tape since last summer), both of which showcased her dark, hypnotic blend of the synthetic and natural, with many sounds and beats culled from numerous field recording trips. In addition to her musical productions, Mitchell has been managing since 2015 the site Many Many Women, an index of female musicians in the “experimental/avant garde” realm. She also writes and presents on representation in music, having spoken at last year’s Pop Conference in Seattle.

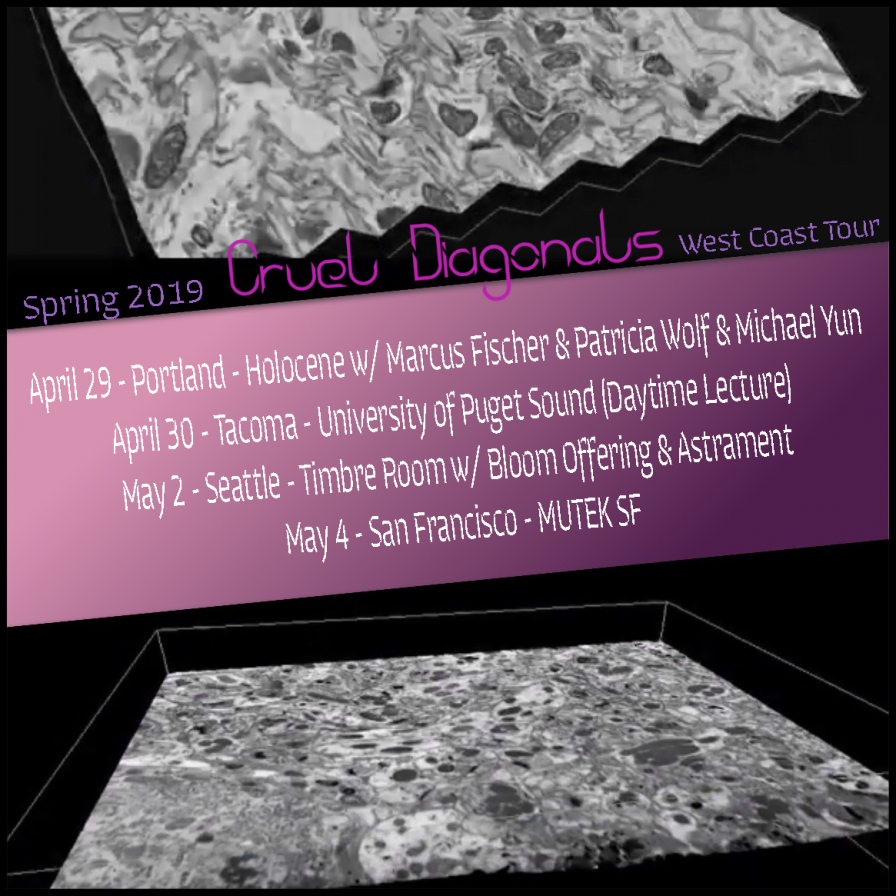

On the occasion of the digital release of Pulse of Indignation and a mini West Coast tour (see tour poster below, which includes a date at MUTEK San Francisco), Megan and I traded emails to talk about her beginnings as a vocalist, field recordings, and the ongoing discussion of giving voice to underrepresented artists in the experimental music world.

Your website states that you are “a jazz and classically trained vocalist.” What were some pieces that served as inspirations or foundations to your training in these areas? When did you start composing your own material? At what point in your training in the jazz and classical world did you form the Cruel Diagonals project?

It’s funny, because nobody has really properly asked me about my vocal background yet, though I consider this to be a big part of my music and compositional process! I started singing very young, around ages 6-7, in musicals at school, and it became quickly apparent to the adults around me that music was something that would be fundamental to my life. I took voice lessons from ages 11-18, and throughout my adolescence, my vocal endeavors ran the gamut of musical theater, jazz choir, jazz solo, vocal competitions, classical, opera, and singer-songwriter stuff. It was always sort of a struggle for me, because I think my voice teacher really pushed me into the classical realm, and I do definitely have this very pure mezzo-soprano voice if I want to use it that way, though I always felt myself gravitating toward jazz standards that had been sung by the greats, like Nina Simone or Billie Holiday. I was a terrible voice student, honestly! I never practiced, and my voice teacher was always incredibly frustrated with me. I did things to appease her, I think, and my parents, as well as the community around me that I had grown up in and had seen me sort of rise to this ingénue “starlet” stereotype. Some of the pieces I performed did really resonate with me, however, and I think were some foreshadowing for some of the avant-garde composers I later ended up loving. I was exposed to these French art songs from the Impressionist movement that were incredibly dark and emotional by composers such as Debussy, Fauré, and the like.

Throughout all this “serious” vocal training, where I was also driving myself to opera practice every weekend, my friend and I had also started a songwriter’s club at our high school, and we’d put on showcases. My music was very typical coffeehouse folk singer-songwriter stuff; I knew how to play guitar and piano at the time (bless my parents; they had also paid for me to take these lessons), so these both made their way into the early music I did as a teenager. None of this is really part of my current day music, but it’s all to say that I’ve been involved in creating music for quite a long time.

Once I got to college and got some distance from this intensive track of vocal training and moving between all these different styles and worlds of musics, I had a rather long period of resetting and reshaping my identity around music. I was the music director at my alma mater’s radio station for three years, so curating became a big part of my musical identity, and I was also DJing a radio show of experimental music there. The genres shifted from semester to semester, so sometimes it was post-punk, no wave, krautrock, minimal synth, psych, experimental electronic, or some combination of those. Once I graduated from my undergrad program, I started making field recordings in a rather rudimentary fashion, just experimenting and trying to ease myself back into the compositional process again. I was pretty heavily influenced by Luc Ferrari during that time period and the book Presque Rien Avec Luc Ferrari by Jacqueline Caux, as well as, of course, my lifetime idol, Pauline Oliveros. The field recordings started making their way into my DJ sets when I would play out in and around Seattle, so I was experimenting there, in a sneaky way, and then I finally picked up a sampler (at a friend’s behest) and started using those in conjunction with my voice run through delay and reverb. Those were the earliest Cruel Diagonals recordings. So now I’ve run you through what is essentially my entire music history, ha!

Your debut album, Disambiguation, arrived last year through Drawing Room Records. Pulse of Indignation was included as a bonus cassette, but was released digitally in January. I’d love to learn about your recording process for putting together the album and EP.

I wasn’t even sure, with Disambiguation, that I was getting at an album, until I started linking things thematically through the field recordings I was capturing. I initially just started sharing the tracks that would later end up on that album with friends through SoundCloud (I believe “Enmeshed” was the first one), and it was sort of this de-cocooning process. At that same time, I started posting these videos of me just singing a cappella jazz standards in my room and posting them on Facebook, and people were so responsive and kind! I realized that almost everyone I knew in my adult life had never heard me sing nor were they aware of my musical background at all, so they were genuinely surprised that I was harboring this talent. It was the combination of the encouragement I received from these videos and the early track iterations off Disambiguation that pushed me forward.

I knew virtually nothing about production, other than some basics about DAWs I had picked up from years earlier when I had recorded demos, so a lot of those early tracks are very rough, production-wise. My dear friend Nicole Carr (Bloom Offering) helped me at first with a sampler, and then I decided to move away from that and work mostly in Ableton. I got some very basic tutorials from two other friends, and then it was just a lot of fumbling through and a lot of frustration, honestly. I am a lot of more adept with the program today, but there is still so much I don’t know how to do very well! Many of the tracks I made, such as “Render Arcane,” were sort of serendipitous mistakes; an amalgamation of field recordings run through effects, reversed, pitched down, time stretched, and a ton of layered vocals. I started making very, very rudimentary beats that I think have somewhat become my signature, ha! I’m not sure. Some publication referred to me as an “experimental beatmaker” the other day, but really I just didn’t know how to quantize or anything like that in a lot of early recordings, so I just let things be really imperfect and allowed this to be part of my sound.

It’s already been said elsewhere that a lot of the source material for both of these albums was culled from early field recording outings around the Pacific Northwest and from the ethnomusicology archives where I worked for a summer at the University of Washington. I sampled (poorly) a lot of the instruments that were sitting in the basement at the archives there and ended up using those, pitched down and distorted. I also used the recordings from all these abandoned “ghost towns” I had visited, such as this old mine shaft up in Mt. Rainier National Forest, and environmental recordings from the abandoned crusher mill and quarry in Concrete, Washington.

You’ve been running the website Many Many Women since 2015. What has been the response from listeners and fellow musicians over the years? Has your approach to managing and curating the site changed?

I feel somewhat sheepish answering this question, because it has admittedly fallen somewhat to the wayside as of late due to more focus on my personal projects, but it still feels gratifying when people acknowledge it and notice the work that has been done. I cannot speak about it without mentioning its creator, Steve Peters, who so graciously handed it off to me three months after its inception. He started it under a certain vision that has only slightly changed under my direction. Overall, the emails and submissions I have received have been overwhelmingly positive and supportive. It’s a wonderful feeling to see the index cited around the internet as a resource for those looking to bolster their curricula in academic libraries or for other like-minded folks seeking to diversify festival line-ups and bookings. I’ve added some curatorial aspects to the site that didn’t always exist by featuring artists on the homepage that resonate with me especially. I think, unfortunately, I don’t have as much time to manage it as I’d like, so I’d love to explore some options in the near future of collaborating with someone. I love the model that female:pressure uses where the artists self-manage their entries in the database, which I think makes a lot of sense, but they also had a grant and a full-blown developer to build out that database model! Many Many Women is just me, a person with a full-time job, who is also an artist, who also wants to help any way I can. It’s probably not fair to continue on and neglect it as I have been.

Your website notes your interest in field recordings, both as a hobbyist and in your music. Can you describe how you incorporate recordings into your music? Do you tend to favor urban or rural sounds?

I tend to use field recordings in my compositions as a point of disruption, like as a jarring, unexpected element to unsettle the listener. A mentor of mine once told me that each of his writings is comprised of the 90% expected, “on brand” voice for him, but that he tries to introduce 10% of the unexpected in each piece to push himself into an element of the unknown and experimental. This has been an approach that I’ve adopted heavily in my work, so oftentimes it’s the field recordings that I’ve made in error — a hydrophone dropping suddenly into a tidepool, brushing up against a mic loudly with a windscreen, or subtle rhythmic elements that I didn’t even notice while monitoring in the field — that make it into my compositions.

As for the types of sounds I favor or gravitate towards: I find myself seeking out juxtapositions constantly in the field. My favorite environments are those that contain a surreal element, so maybe this is a rural environment with abandoned industrial foundations (see: the numerous mining and logging towns or factories I sought out while I lived in the PNW), or an urban environment that contains some hyperrealistic homage to nature within it. These juxtapositions are often what drive the nature of my music; the tonal and the harsh, the grainy and smooth, the dark and ethereal. I don’t seek to achieve a natural conclusion between these elements, but rather to present them in tandem as an option for considering the many nuances and complexities that exist in the emotional experience.

When you listen back on field recordings you’ve made, what are some that continue to inspire you, or at least surprise you, even if you haven’t used it in your music?

Some of my favorite field recordings are still a series I’ve made over time of contact mic recordings under different bridges, which started in 2013 on a trip to Tacoma. That recording was one that I thought was trash and ended up cutting it off short, but realized later it was rhythmically compelling and ended up using it later in “Liminal Placement” off Disambiguation. After that, I was sort of entranced by cars driving over bridges and tried to find different types of bridges made of differing materials where I could safely post up and record. I’ve got four different sessions of these contact mic bridge sessions, and I’ve used more of those recordings since in tracks of mine.

On a similar note, you recently moved to L.A. after a long time in Seattle. What kind of field recordings have you collected since the move?

I’ve sadly not had a ton of time to work on field recordings since I moved here, but my fixation since I moved has been tunnels, definitely. I became entranced with tunnels after my friend Shannon Kerrigan (Geological Creep) and I went on a trip through the Snoqualmie Tunnel in 2014, and it was this deeply meditational, pseudo-psychedelic experience, because it’s this two mile-long tunnel that was formerly used by trains to connect through the Cascades from western to eastern Washington. It’s dark almost all the way through, so we’d push ourselves to try and walk through in pitch black, which is like a sensory deprivation experience that can get pretty frightening and, like I said, somewhat psychedelic. After this, I became kind of obsessed with tunnels and the recordings I could get out of them, as well as just the transformative nature they could provide. I have crowdsourced some tunnel coordinates from local L.A. friends and have visited two, and have made recordings at both those sites. One of them was where I made the viral Twitter video of me sledgehammering rocks. I also got a GoPro last year, so I’ve been recording video alongside these recordings, where I often sing. I’ve additionally been experimenting with making just pure field recording videos, such as some hydrophone recordings of tidepools while I was in Maui last year and the underwater video I took, just to keep things interesting!

Cruel Diagonals released a track with Longform Editions, “Monolithic Nuance.” How did you end up getting connected with that label? Did you go into recording with a mindset that an idea would be better suited in the sprawled out form that LE favors versus writing songs for an album?

Andrew Khedoori of LE reached out to me directly! He had heard my music and asked me to participate, which was such a unique and different challenge for me, so I agreed (although the due date was a mere month after I moved in to my new place in L.A., so the timing was quite stressful!). I had never been given a prompt before when writing a composition or piece of music, so this was actually a huge confidence booster as a musician. I had had this sort of imposter syndrome about being a “legitimate” musician, because of the very haphazard nature in which I had produced my debut album and EP, so the notion of being approached to compose something with intent was quite frightening. Thankfully, right around this time, I had begun experimenting more with Eurorack modules and that had been lending itself to these more drawn-out, lengthy pieces that inhabited this much more improvised domain than before. I felt more comfortable sitting in a space for longer and making more minor tweaks (although my greatest fear, still, is boring my listeners). It made sense to me, then, to write this composition in “movements,” and that’s how “Monolithic Nuance” came about. My favorite tidbit about that piece is that one of the sound sources from that track is a field recording of a breast pump that my coworker let me record!

Many Many Women, your work as Cruel Diagonals, and your academic research have focused on marginalized voices in music, specifically women, non-binary persons, and non-men. With your work across different platforms, have you noticed changes in bookings, label representation, and coverage on music publications? What are your thoughts on what can be done to make those sounds and voices less marginalized?

By and large, yes, I think there is more cultural awareness of the fact that it isn’t acceptable to book an entire festival lineup of cis white men, and people are much more attuned to this because of so many vital organizers. I know, for example, that Electric Indigo stated in her RA Exchange interview that CTM Festival specifically reached out to female:pressure after they published their first FACTS report in 2013 and said that they were rectifying their lineup distribution immediately in direct relation to the work that came out of this. So, the work is not being done for nothing, and I think that’s wonderful, but of course, change moves slowly and at differing paces in different arenas. There are still things that happen with great frequency in the experimental music world to marginalized folks that are entirely frustrating, like publications using an image of a black queer person as the lead photo on an article where that person’s work isn’t even discussed (it looks a whole lot like performative progressiveness, y’all). Some basic thoughts I have are: hire marginalized folks in all walks of the music industry — writing, editing, production, mastering, booking, etc. This will help avoid some very basic mistreatment (duh!) right from the get-go. Another angle that I’ve focused on, from an archivist’s standpoint, has been from that of pedagogy and collection management and development. This is something I spoke about last year at the MoPop Pop Conference, and continue to research and look into for further talks. I’m interested in approaching inclusion and a multitude of voices from the standpoint of archival practice and policy-making, and by adopting a feminist pedagogy in academic organizations. This means, in essence, that sources of knowledge are more varied than the “traditional” sources, which have been predominantly white, male, and cisgender, and that popular rhetoric, oral heritage, and other resources are given equal value as resources for consideration within the canon of music history and, by extension, curricula.

What’s next in 2019? Any further sounds, live shows, presentations?

I’ll be doing a cute little West Coast tour, with dates in Portland, Seattle, and San Francisco, where I’ll be playing MUTEK SF. I’ll also be giving a talk at my undergrad alma mater in Tacoma, at the University of Puget Sound, during this tour, on the intersections of gender, music, and archives.

I’ve also begun collaborating on music endeavors, which is a new thing for me entirely, so we’ll see what comes of that!

More about: Cruel Diagonals