It has become increasingly difficult to consider Bill Orcutt’s playing beyond the (self-)problematized framing and paratextual acrobatics within which it is embedded. Orcutt delivers his performances with provocation (his 2015 release Colonial Donuts featured something like a Google Image array of Bob Marley tattoos etched into white skin). He puts immense attention into his titling and curation of repertoire to deliver precise postmodernist collisions (2013’s A History of Every One took its name from Gertrude Stein and sat blues laments next to the hokey “feel good” themes representative of traditional, white America). Additionally, his output via his own Palilalia and Fake Estates labels constantly dare fetishistic collector-completists to keep up (this includes the 13x7” box set Twenty Five Songs — an edition of 70 — and the just-released computer music album An Account of the Crimes of Peter Thiel and His Subsequent Arrest, Trial, and Execution in an edition of 100). Beyond these strata, it is indeed easy to forget what brought us here: Orcutt’s innovative, peculiar, unique, and wholly enjoyable playing. Bill Orcutt seeks to remind us of this, a gesture that, laughably, can hardly be taken at face value.

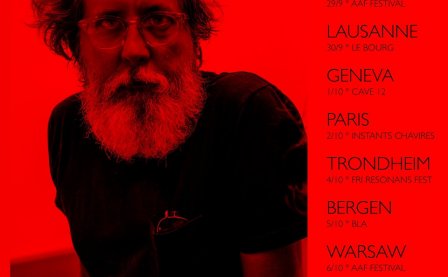

Bill Orcutt is a mid-career eponymous release. This is a familiar signifier of artistic reinvention. Recently, Slowdive and Dirty Projectors partook in this cue to highlight reunion and breakup, respectively. From a marketing standpoint, the mid-career self-titled release can also demonstrate the creative director’s intent to introduce the artist to formerly unfamiliar audiences. Last year, this was deployed sardonically by Karl Blau for his 40th-ish record Introducing Karl Blau, a studio pop-country album. I get the sense that there was a similar smirk in the room when Bill Orcutt received its title and cover. Nonetheless, the titling is functional in signifying Orcutt’s first studio full-length fixed upon solo electric guitar. It lifts the album up from a labyrinthian discography. It is a plaque alerting onlookers to a significant milestone in a narrative that might otherwise be lost or irrelevant.

Bill Orcutt can be viewed as the follow-up to A History of Every One. It resolves the dissonance built up through those first three solo records (2009’s A New Way To Pay Old Debts, 2011’s How The Thing Sings, and 2013’s A History of Every One), taking familiar repertoire and delivering it casually, digestibly, and, most significantly, apolitically. Orcutt returns to the more idealistic, Christian, and puritanical selections worked between A History of Every One and Twenty Five Songs, and mixes them in with two original works (“The World Without Me” and “O Platitudes!”) and an explosive yet true-to-form rendition of Ornette Coleman’s crowd-pleaser “Lonely Woman.” Bill Orcutt is overwhelmingly polite.

This is especially so, as Orcutt turns to the electric guitar, which, at this outing, begs less aggressive attack and rounder, fuller phrases from Orcutt’s hands than does his acoustic. Additionally, listeners are no longer threatened by Orcutt’s intense moan, which has persisted through the majority of his recordings to date. His idiosyncratic virtuosity is neither diminished nor over-indulged; instead, his harsher edges are tastefully subdued, delivering a version of himself that is uncharacteristically presentable.

Comparing the version of “Star Spangled Banner,” which closes Bill Orcutt, with the acoustic 2012 video take (something I’ve found to be a great introduction to those who hadn’t heard his work), I find the delivery to be now less antagonistic toward the anthem it dissects. In the video, each note is approached with a wildly violent pluck, threatening the guitar itself and asserting that the song may become undone at any given moment (although it does not). 2017’s version takes that step and pulls the composition apart, presenting a portrait of America with its components in place but one that forgoes the nationalist patriot’s imaginary vision of what America stands for. In the place of this missing fiction sits the expression of Orcutt’s musical voice. As wild as this voice is, it is nonetheless convincing of Orcutt as his inimitable and individual self, a foundational myth of its own. As such, Orcutt’s bombastic flourishes ironically align himself with the countless singers who decorate the anthem with endless melisma’s before sports fans every night. They also maintain the anthem’s legibility but inject the patriotic tune with their own individualistic spin, reminding Americans that their anthem and their nation permeate through all of us, transcending difference.

As Orcutt delivers a particularly curatorial product (with decisive packaging, sequencing, inclusions, and exclusions), he toys at the techniques of branding as they intersect with musical identity and neoliberal selfhood. Orcutt’s position has generally been to intervene and complicate. In the October 2011 issue of The Wire, he states:

A lot of the 60s blues guys and people today treat it in an uncomplicated way. […] So I always try to just complicate it a little or at least indicate visually that there’s a discontinuity between what I’m doing and my position in connection with this music and its origins. I can’t justify it ultimately. My connection to the blues comes from buying the records. I saw Muddy Waters play once. I have no authenticity in connection to the blues.

Orcutt now importantly turns that problematizing trick in on itself and creates a collection of takes that is at once a full-fledged expression of renewed musical identity (a novel twist on Orcutt’s familiar set of compositions, techniques, and vocabulary) and a mockery of the mechanisms of selfhood that carry it. It is important to both note and problematize how such a position has been constructed through the privileged exploration of a meticulous artistic voice and narrative. It is also worth considering contemporaries who make similar challenges without engendering the process that is the subject of their critique. Nonetheless, Bill Orcutt serves as a useful object lesson in the nuanced workings behind flexible narratives of the neoliberal self as they relate to the artists we follow. Its musical value (its enjoyable restatement and development upon Orcutt’s past work) is unscathed by the embedded critique of the process which birthed it. This “return to form” finds the artist “in a new direction” with results that feel “right at home.”

More about: Bill Orcutt